The 1920s: Entering the Corporate Age

Examiner, Sept. 27, 1924, p.14. The Cecil B. DeMille epic: a Paramount Picture released by the Famous Players—Lasky Corporation. A year later the Grand Opera House, with local ownership, would fall, less than romantically, into the arms of Theatrical Enterprises Ltd., a 100 per cent subsidiary of Famous Players.

Examiner, Nov. 4, 1925, p.11. Released in August that year, the first Chaplin feature released through United Artists, the company Chaplin co-founded with Mary Pickford, D.W. Griffith, and Douglas Fairbanks. To encourage attendance: “Buy a script book.”

DeMille and Chaplin (among many other artists of the time): the silent feature reaching the height of its particular art in the 1920s . . . and, in 1920, below, a variety of “amusements.” For much of their history, the ads for both live and motion picture attractions were embedded in the sports pages. The lengths of programs continued to increase, and prices went up a little too.

Examiner, May 22, 1920, p.11. A day of sensational offerings. The ubiquitous minstrel show. Tyrone Power (the father) and “The Wonderful Nance O’Neil” (also a film star, and promoted as “the American Bernhardt”) in person, on stage; Constance Talmadge (sister of the more famous Norma) and Evelyn Nesbit (her name mispelled in the ad) on screen. If you’ve read E.L. Doctorow’s novel Ragtime (or seen the movie, 1981) you have encountered the fictionalized story of the famous Thaw-White trial: Nesbit’s strange 1906 involvement with architect Stanford White and Harry Kendall Thaw in what was (at that early time) called “the trial of the century.”

In February 1919 the Toronto theatre magnate Ambrose Small bought the Grand Opera House outright from the local owners, the Turner family, adding it to his theatre empire (although the evidence suggests he had his fingers in it long before that). In late autumn of that same year he promptly sold all his theatre holdings, including Peterborough’s Grand, to the Trans-Canada Theatre Company. Perhaps he had needed to own it entirely by himself before putting through that deal. But then Small mysteriously disappeared on Dec. 2, 1919, never to be seen again. (As I could say again and again in these pages, that’s another story, recently deliciously told by Katie Daubs [of the Toronto Star] in The Missing Millionaire: The True Story of Ambrose Small and the City Obsessed with Finding Him, 2019.)

Review, March 17, 1915, p.8. The older Tyrone Power in a moving picture at the Empire; he came to appear on stage more than once too.

Under Trans-Canada, based in Montreal, the Grand Opera House continued to present its mixed bag of big motion pictures and live attractions — and to draw large audiences. Tyrone Power (not to be confused with his son, the movie actor Tyrone Power) is another of those famous actors who appeared on stage in Peterborough more than once. Minstrel shows, with their stereotypical and blatantly racist portrayal of Black Americans, long remained a “guaranteed attraction” in Peterborough, as they were across the continent — and mainstream motion pictures carried on the tradition, especially in the 1930s and 1940s. The Grand Opera House was a busy place. The city, with its population of 23,000, also had the Allen, Strand, and Empire, with changes to come.

But the national theatre chain was short-lived; by 1923 the Allens were bankrupt — victims of both over-extension and cut-throat competition with their main rival, Famous Players, which had a corporate reach from the United States into Canada. But before that, around the beginning of December 1921, the Allens concluded a deal to sell the Peterborough theatre back to Mike Pappas, who re-opened it once again as “The Royal.”

From the Strand to the Regent to the Capitol

Meanwhile, what was then the longest-running motion-picture site — 408 George had been home to the Crystal, Red Mill, and Strand since 1907 — was reaching the end of its days.

Examiner, May 21, 1920, p.12.

Examiner, May 31, 1920, p.9. On a Monday, the Strand’s last ad: “Watch for the Opening of our New Theatre.”

Only a few days after closing the Strand, as promised, the local owners, Schneider-Rishor Ltd., replaced the Strand with the larger and spanking new Regent Theatre, just around the corner at 139 Hunter Street East.

Examiner, June 3, 1920, p.9. Opening night price, 25 cents a ticket. The place is called a “show house” and the movie a “motion play” — and, as a subject, “snobbery” is apparently a drawing card. The Regent would have a relatively long life — to 1949. But it would soon be displaced as “the favorite amusement house of the city.”

Examiner, June 4, 1920, p.12.

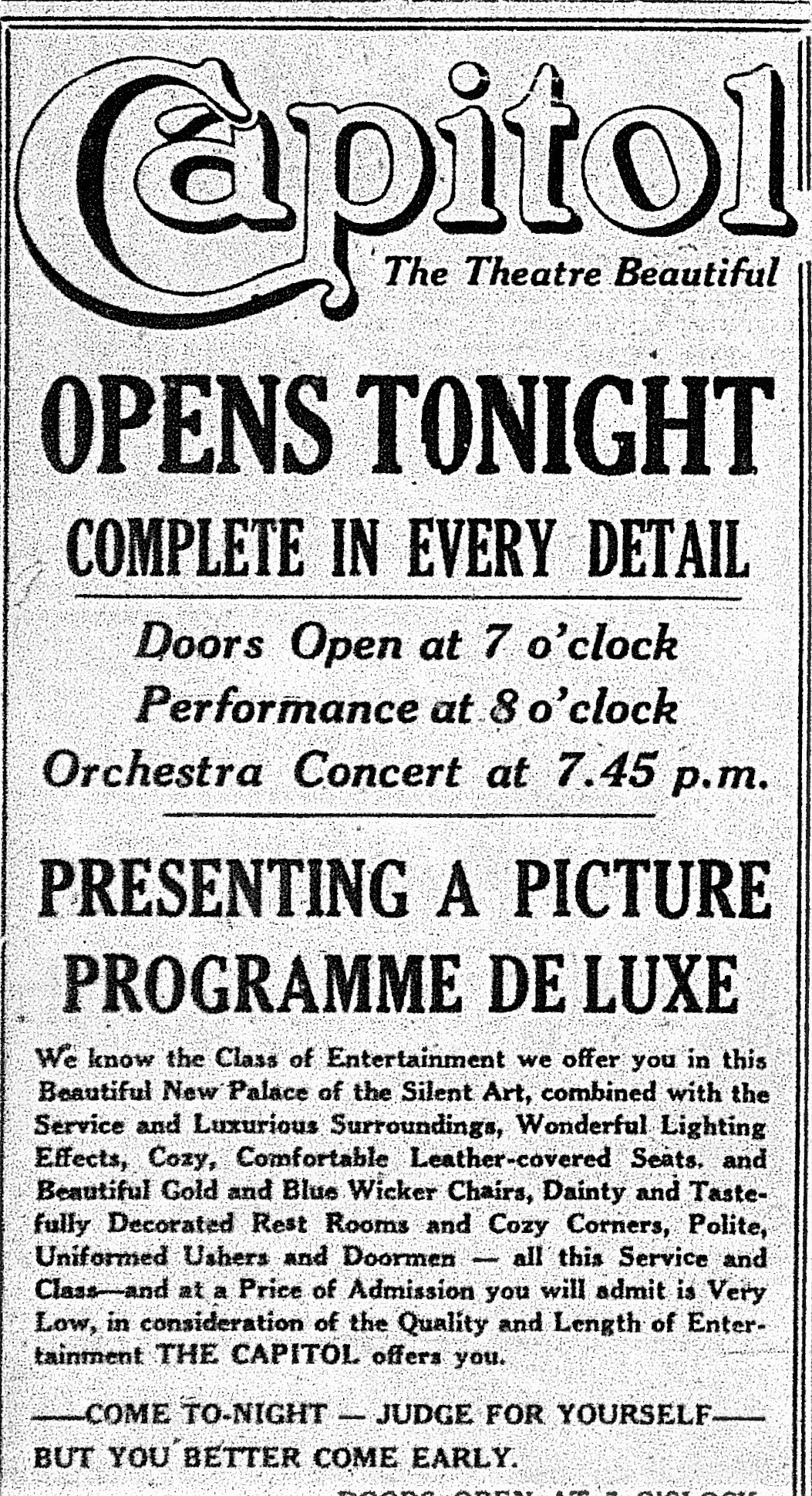

Less than a year later the corporate age of movie exhibition was consolidated in Peterborough with the building and opening of the Capitol Theatre, owned by Paramount Peterboro Theatres Ltd., which was a subsidiary of the Famous Players Canadian Corporation chain — and vertically integrated with the U.S. Paramount Famous Players-Lasky Corporation.

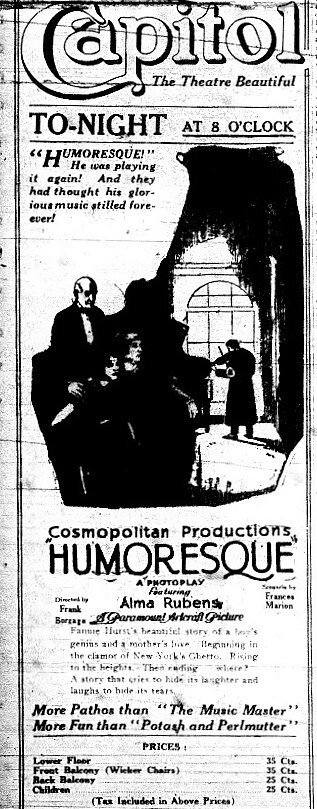

Left: Examiner, April 18,1921, p.9. Middle: Examiner, April 21, 1921, p.15. Right: Examiner, April 15, 1921, p.15.

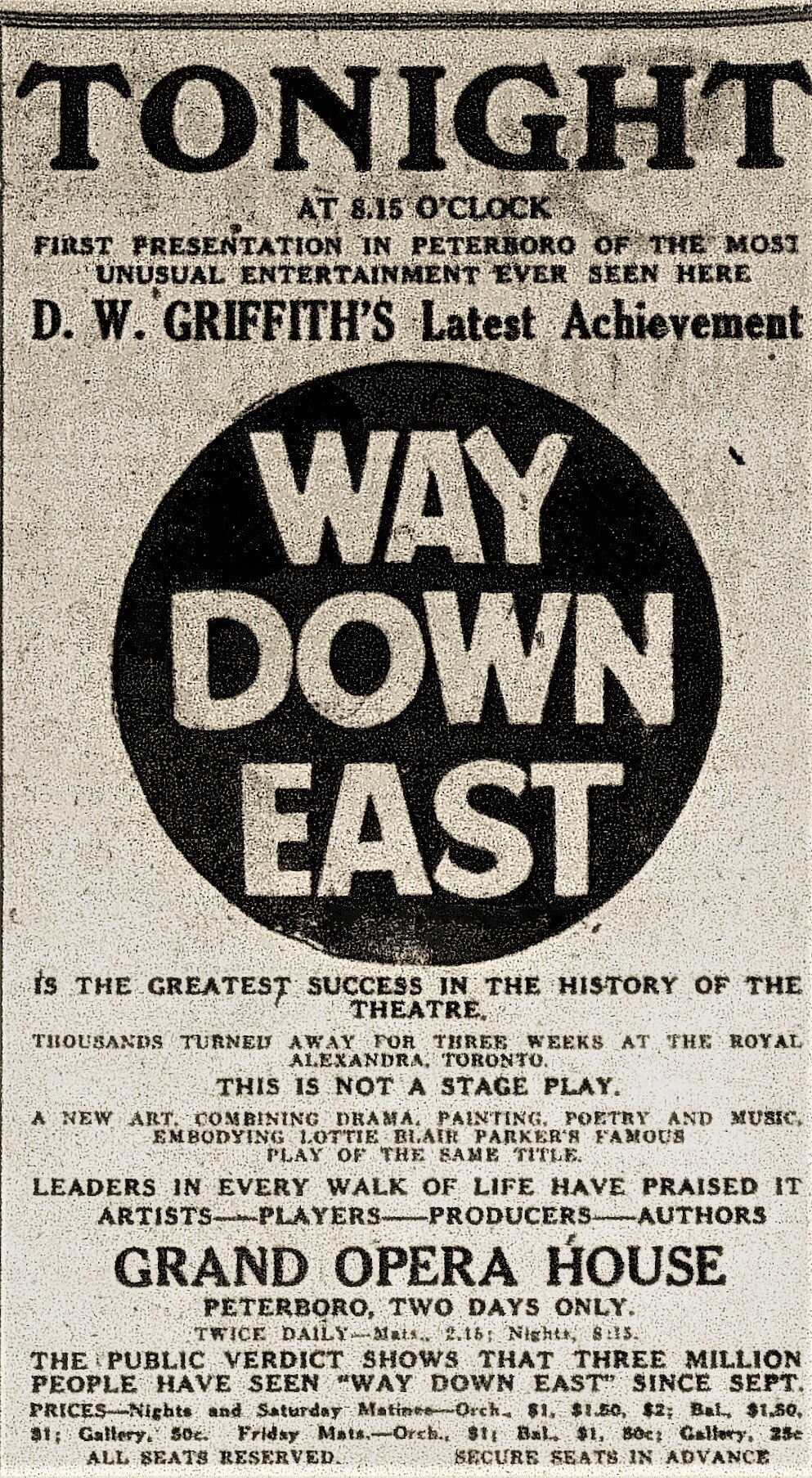

The Capitol, complete with its fancy blue wicker chairs and dainty restrooms at 306–8 George Street N., was just a few doors north of the Grand Opera House, which was announcing Griffith’s big movie Way Down East (1920) and this time finding it necessary to declare: “This is not a stage play.” When Way Down East reappeared at the Regent Theatre in May 1924, a promo piece in the Examiner noted that the film “will be shown in this city for the first time.” (The accompanying ad mentioned, more appropriately, “first time ever” at more popular prices.)

The Empire fades to a dissolve, with no fond farewell

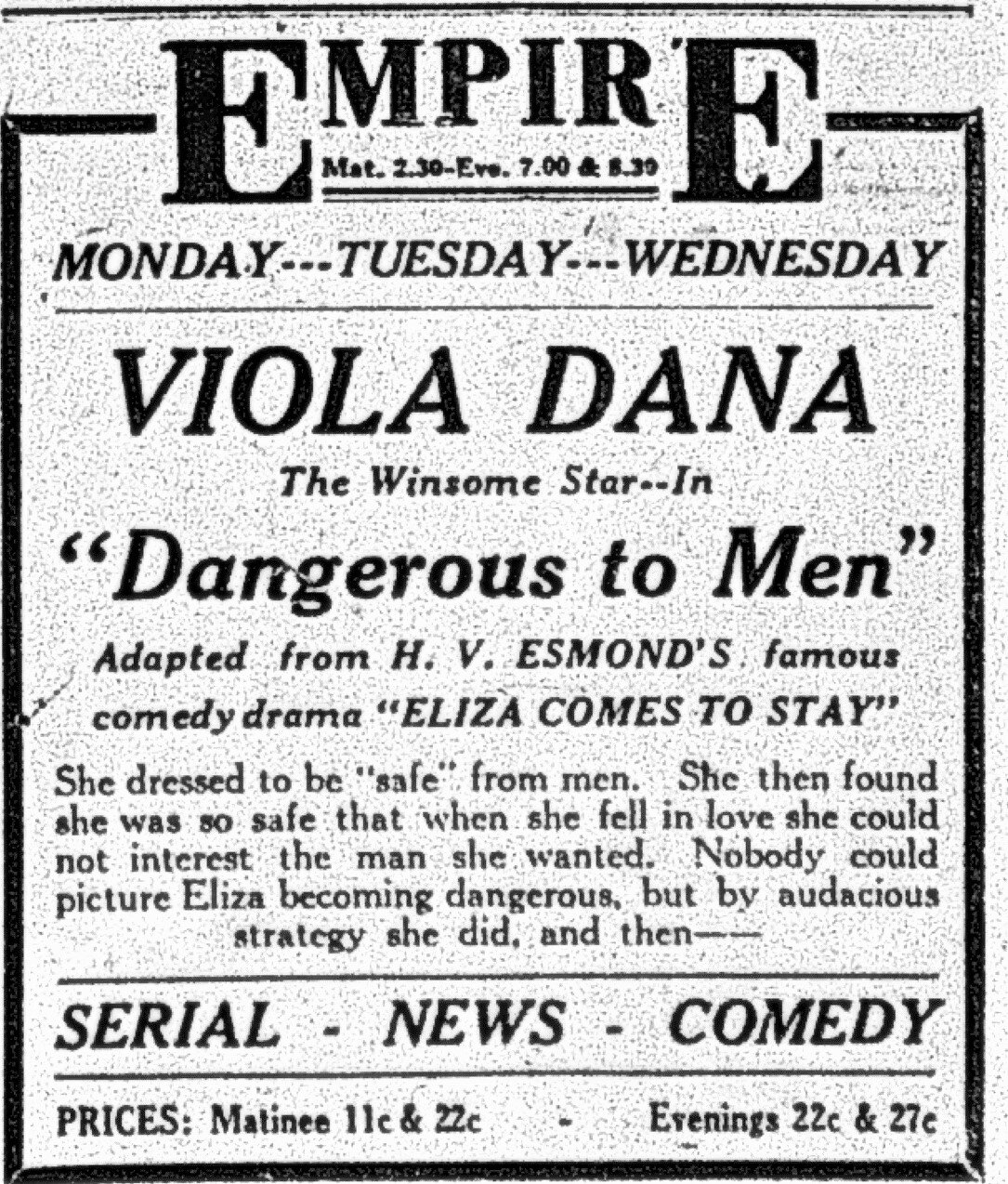

Left: Examiner, April 25, 1921, p.9. Right: Examiner, April 28, 1921, p.11.

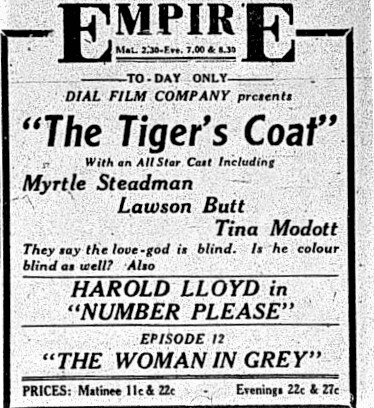

The Empire closed its doors after this final showing — featuring the silent film comic Harold Lloyd and the Italian-born Tina Modotti (with part of her name missing in the text) — on April 28. Ownership had shifted from veterinarian Robinson to Charles T. Porter and his wife, Muriel.

The Empire’s last program featured a serial and the silent film comic Harold Lloyd, but also, in The Tiger’s Coat (1920), with part of her name missing in the ad, the Italian-born Tina Modotti. After this film (her last), Modotti moved to Mexico and as a photographer and photojournalist (and member of the Communist Party) became part of an artistic and political community that included the painters Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. My friend Brenda Longfellow made a beautiful movie about her: Tina in Mexico (2002).

Pappas jumps around from here to there . . . the Grand has new owners

In the first five years of the 1920s, long-time local theatre impresario Mike Pappas was hard to keep track of, constantly bouncing back and forth from one theatre to another, and in and out of ownership. After selling the Royal to the Allens in August 1919, he apparently went into the real estate business. In October 1921 he began managing the Regent, but two months later took over the Royal again. In August 1923 he sold the Royal to Dominion Films and passed on all his current contracts for films to the Regent — and disappeared from the news for a while. In March 1924 he popped up once again, back managing the Royal, but only for a couple of weeks.

Examiner, Nov. 29, 1921, p.5. In December 1921 the Allen became the Royal once again. By this time the Allens were disposing of many of the links in their theatre chain, a year or two before declaring bankruptcy. Although this ad indicates that the Royal, once again under the ownership of Mike Pappas, was “commencing to-night,” it actually did not open until Thursday, Dec. 8. Pappas, who had been managing the Regent for the past month, promised he would now avoid “amateur or ‘fly-by-night’ cheap vaudeville.”

Examiner, Dec. 7, 1921, p.10. It seems the number of reels being offered was still of considerable importance.

Examiner, Nov. 28, 1921, p.10.

Examiner, Dec. 7, 1921, p.10. By 1923 Trans-Canada Theatre Company had failed and gone into liquidation. In September 1924 a local business/press triumvirate took over the Grand Opera House: Roland Glover, Robert R. Hall, and Gustavus (“Gus”) L. Hay.

Examiner, Nov. 28, 1921, p.10. The Regent, with Pappas managing the program, before he returned to the Royal. Here the Regent was offering episode 7 of Double Adventure. The theatre would gain a reputation as “the top serial house in the city.”

Examiner, July 13, 1922, p.11. Here, unlike the corporate owners of the Capitol, Pappas can boast about taking a trip to Toronto to select films “personally” for the Royal. Tom Mix was one of the most popular Western heroes of the decade — and he made a personal visit to the Peterborough Exhibition in June 1930.

Examiner, Sept. 1, 1923, p.11. Despite being still considered an “independent” under the local Schneider-Rishor ownership, the Regent was quietly forging a connection to the Famous Players conglomerate.

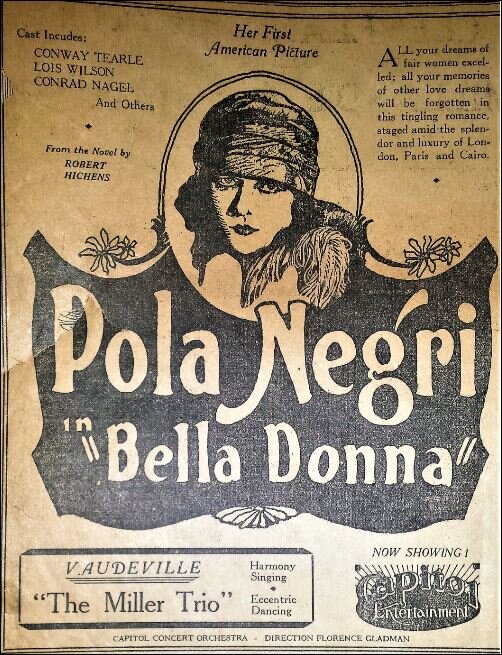

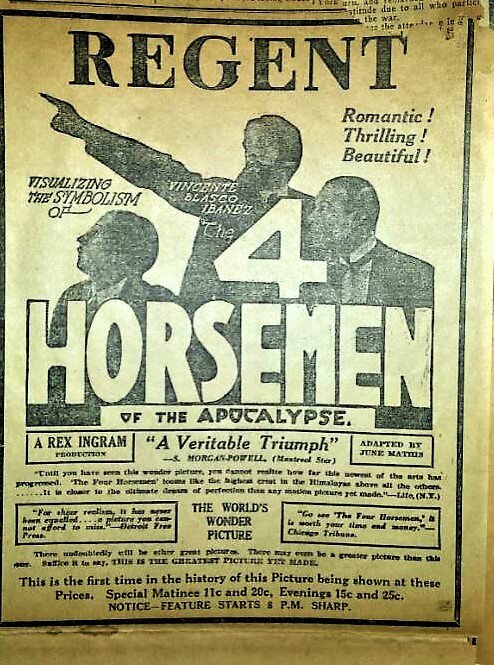

Left: Examiner, April 16, 1923, p.9. Right: Examiner, April 16, 1923, p.9. The Capitol plays the newest film going — and Pola Negri in her first U.S. picture — released by Famous Players—Lasky that month, with a live stage act as part of the program and the assistance of the local Florence Gladman Orchestra. The Regent plays a re-run of Four Horsemen, which appeared at the Grand a year and a half earlier at higher prices.

Examiner, Aug. 22, 1923, p.11. At the top of the ad: “Positive proof that film-making is an art.” (You can see it on YouTube and judge for yourself.)

Examiner, Dec. 4, 1923, p.17. Once again, Peterborough audiences get to see Birth of a Nation.

Promoting Sherlock Holmes — Around about Town

In the 1920s the exhibitors honed their promotional strategies, often quite imaginatively. When the Grand Opera House – competing with three other theatres in the first half of the 1920s – screened the movie Sherlock Holmes, starring John Barrymore (1922) in late 1922, management initiated “a hunt for a replica of the famous Lansdowne pearls, stolen by Professor Moriarty and recovered by Sherlock Holmes.” The Grand placed a string of pearls (costing $3.50) somewhere in the city on the top of a telephone pole. It “induced” a local jeweller “to put an expensive string of pearls in his window with a suggestion of pearls as an appropriate Christmas gift,” along with a card connecting the pearls to the Sherlock Holmes hunt.

Moreover, the opera house connected with the toy department of a large department store, which placed a card in its window announcing, “Sherlock Holmes informs us that Moriarty, Europe’s Master Crook, visited our toy department while in the possession of the stolen Lansdowne pearls. Why don’t you?”

Examiner, Dec. 1, 1922, p.17.

The Grand also published a map in the Examiner, showing the streets and Moriarty’s route through town, with Sherlock Holmes providing clues: “Warm on the trail of the Lansdowne Pearls . . . Hot – Hotter – Stop – Look – Here!” The lucky person who found the pearls got to keep them, of course, but also: “Here’s a couple of seats for your trouble.”

(The promotional gimmick made the pages of Motion Picture News, published out of New York, Jan. 20, 1923, p.316.)

“Wind up the day right!” Pappas and the Royal abandon the set . . . leaving the magic of sixteen teller girls from the Ziegfield Follies, cowboys (with dogs), Sunrise — and a local movie reviewer

Examiner, April 16, 1924, p.11. At the end of March 1924 Pappas, with his personal touch, was back at the helm of the Royal for what would be his final, and very short, stint. This was the last ad with his name on it. In the following months Glover, Hall, and Hay, co-owners of the Grand Opera House, also took over the Royal. By 1929 Pappas and his family had left Peterborough for Toronto, leaving a long, fascinating, and dusty trail of movie exhibition behind him.

Examiner, Dec. 31, 1924, p.11.

Examiner, Oct. 20, 1927, p.13. Again, a serial presentation, Melting Millions.

Tom Mix was one of the biggest Western stars of the 1920s — and he had his dog Duke to go along with his horse, Tony. But the most famous dog of the time was Rin Tin Tin. Pundits claimed that the dog helped the Warners studio pay for its prestige features through the decade. As one publicity come-on put it, “The coming of Rin-Tin-Tin to the Regent is much like the coming of the circus: neither ever loses drawing power.”

Examiner, April 27, 1925, p.11. Introducing “Miss Kathleen McCarthy (Jeannette of the Examiner).” An avid reader and writer since her teen years, Cathleen McCarthy (the “C” for Cathleen was the most common spelling over the years) started working at the Examiner in 1920. As the only woman on the reporting staff she was quickly placed in charge (not surprisingly) of the “Society” or “Women’s” pages. But she soon began doing reviews of motion pictures — making her an early pioneer of that work — and continued doing so until she left the paper in 1937.

Examiner, Feb. 11, 1926, p.11.

Examiner, May 12, 1925, p.15. In the mid-1920s to draw crowds the Royal had “Popular Song Nites” – “Hear the New Ones!” — and special evenings of “fine music,” but also, as here, on Monday evenings, “Country Store Nite,” with “prizes and surprises galore!” for lucky audience members. These kinds of special lures would continue into the Depression of the 1930s and to the “Foto Nites” of the 1940s and early 1950s.

Examiner, Dec. 12, 1925, p.15. Despite the wording in the Royal ad, above, no improvements were forthcoming. Packed houses or not, the theatre’s doors were firmly closed following that last Saturday program.

The Royal proved a victim of the Famous Players Canadian Corporation’s drive to stifle the competition. That year Famous Players had acquired Trans-Canada Ltd. and Theatrical Enterprises; and in November 1925 both the Grand Opera House and the Royal Theatre were “transferred” to Theatrical Enterprises. One of the first actions was to close the Royal.

The Royal, opened in 1908, was now finished. Its space remained virtually unused until 1939, when the Centre Theatre was opened on the same site.

Examiner, Feb. 13, 1925, p.15.

As for the Capitol, it was assured life as one of the “show places of Canada.”

Cathleen McCarthy (writing as “Jeannette) reviewed North of 36 (1924), a cattle-drive film, on Feb. 13, 1925, comparing it to The Covered Wagon, an expensive Western epic and the most popular movie of 1923. Several scenes in this new film, she said, had a “strong resemblance” to the earlier film, especially in its “atmosphere [of] reality” and its “lighting effects,” with the same “white, clear light” flooding the shots of the cattle drives. A particularly interesting thing about the ad is how it puts Peterborough on the corporate map when it comes to the “show places of Canada.” In Peterborough, the ad was saying, film-goers could see exactly the same movie as others were seeing elsewhere (in bigger cities), for the same regular price — and you would also get the hockey results.

Left: Examiner, Feb. 23, 1928, p.13. Right: Examiner, May 13, 1929, p.13.

Examiner, June 4, 1928, p.9. And this last ad appears to end with a typo: “Plain” Opens Thursday” — or “Plan”?

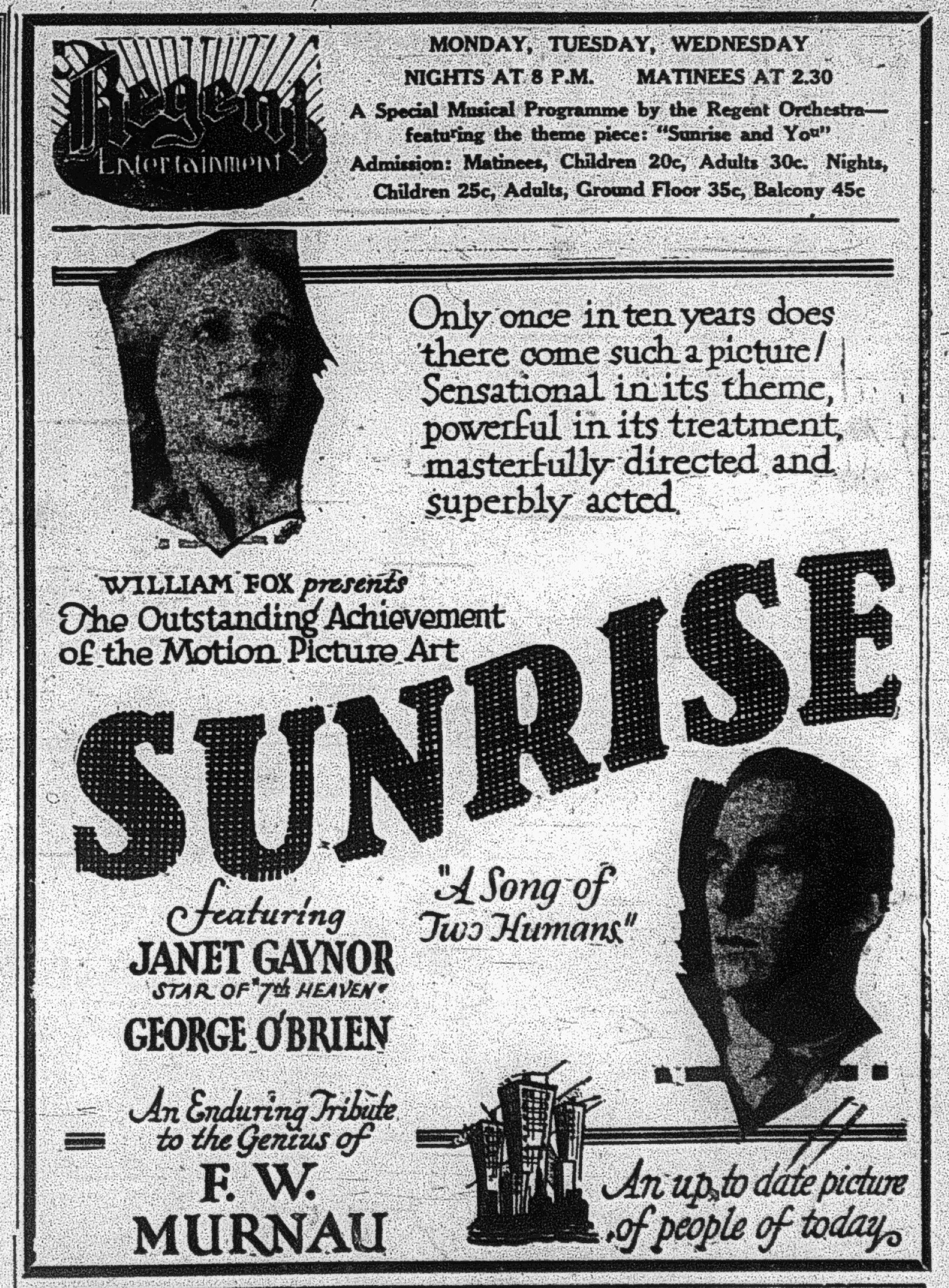

The Regent generally had second-run or cheaper features — but in this case it was screening a film that over time has stood out above the rest. “An up to date picture of people of today.” It might have been that rarest of times when the advertising claim (“Only once in ten years does there come such a picture . . .”) lived up to its promise. With sound movies arriving in that same year, Sunrise (1927, directed by F.W. Murneau) might have been the last of the great silent features.

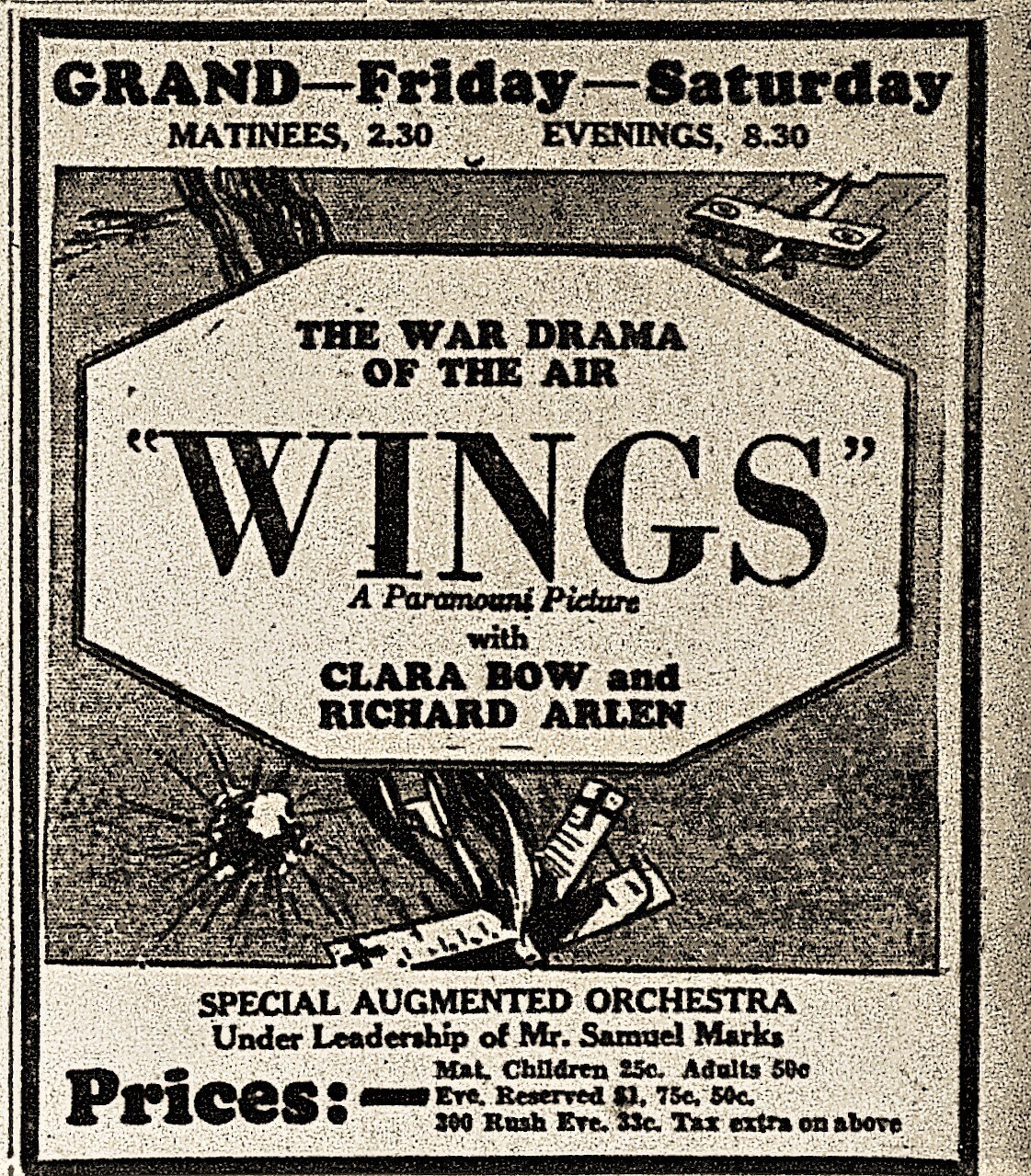

The Grand Opera House soldiered on, a peculiar mixture of local ownership and a restrictive lease to Theatrical Enterprises, the Famous Players subsidiary. From 1925 to 1930 it had fewer live shows and, at least until 1928, more motion pictures. After being screened in February, Wings returned for a June 9, 1928, re-run, at lower prices. From what I’ve found so far, Wings (1927), the winner for Best Picture at the first Academy award ceremony in 1929, has the distinction of being the last motion picture to be presented in the declining life of the opera house.

It was also the subject of a wonderful article by Jeanette (or Cathleen McCarthy): “He Sees Wings” — a rare glimpse of a local movie-going experience.