The 1930s: Talkies and the Great Depression

George Street, west side just south of Charlotte St., c.1931. Look up, look way up towards the top of the photo — follow the pointing finger across the road to the Capitol and catch the “Talking Pictures.” Under the name “Capitol” the sign also indicates: “Three Performances Daily 2:30 7:00 9:00.” The sign was there until 1932, when the buildings on the south-west corner of George and Charlotte were torn down to make way for the Canadian Department Stores building (later Eaton’s). This is a detail from a larger photo; Peterborough Museum and Archives (PMA), Park Studio, P-12-881-1.

Talking motion pictures in which the simultaneous timing of action and sound is all times assured have been announced and demonstrated by the General Electric Company. The process, the result of several years of experimenting in the General Engineering Laboratory of the company [in Schenectady, N.Y], means but slight change in standard motion picture projectors. . . . Both the picture and the sound are recorded on the same film.

– “Talking Movies Demonstrated . . . Excellent Results,” Peterborough Examiner, May 13, 1927.

*****

Combining motion pictures with sound had been an ambition of inventors since the beginning — and Thomas Edison himself had tinkered with the possibilities for years. By the mid-1920s the technology was ready for commercial exploitation. In June 1929 the Capitol Theatre, following a continent-wide trend, was rewired for sound; the Regent did the same a few months later.

Examiner, Feb. 9, 1929, p.13. The Jazz Singer is usually cited as the first “talkie.” Well, the “whole country” might have been talking, but not this film, at least as it appeared in Peterborough. It was in essence the silent version, not sound.

Examiner, June 7, 1929, p.7. The last silent film at the Capitol. Clara Bow and Laurel and Hardy a few days earlier would also have been silent.

It was immediately after The Barker, early June 1929, that the Capitol switched to sound. Warner’s famous feature-length “talking picture,” The Jazz Singer, had opened in October 1927 in New York City and went into general release in December — but it was actually a silent film with two brief passages of dialogue added (a purely silent version was also widely, and successfully, released, including in Peterborough).

The Jazz Singer was not, as legend would have it, the first feature talking picture: other hybrid silent/sound attempts from Warner preceded it. When the silent version was screened in Peterborough in February 1929, it came accompanied by a phonograph machine and a disc recording, which, according to Jeanette (Cathleen McCarthy), writing in the Examiner, gave the audience at least “an idea of what ‘the talkies’ will be like when we get moving pictures along the new lines.” About four months later those “talkies” arrived in the form of The Broadway Melody (MGM, released June 1929) and other shorts on that same program.

Examiner, June 8, 1929, p.13. The arrival of the first talkie.

As for the audience, the theatre apparently had to “turn them away” that first day. According to Jeanette, the first words spoken on a Peterborough screen were: “I want you to go there and no-one else. Sit down. This is your last chance.” And, she concluded, “With these historic words, the talkies made their debut in Peterborough.”

Those words, though, did not come from Broadway Melody (I have, of course, checked). Presumably they came from one of the other pieces of that day’s program, which also consisted of “comedies and short films . . . all being of a conversational variety.”

Examiner, June 10, 1929, p.13.

Examiner, Sept. 3, 1929, p.13. The Regent introduces talking pictures too, another musical.

Examiner, Oct. 12, 1929, p.13. All singing and talking. For a while the movie advertisements kept reminding readers that they would be seeing “all-talking” pictures.

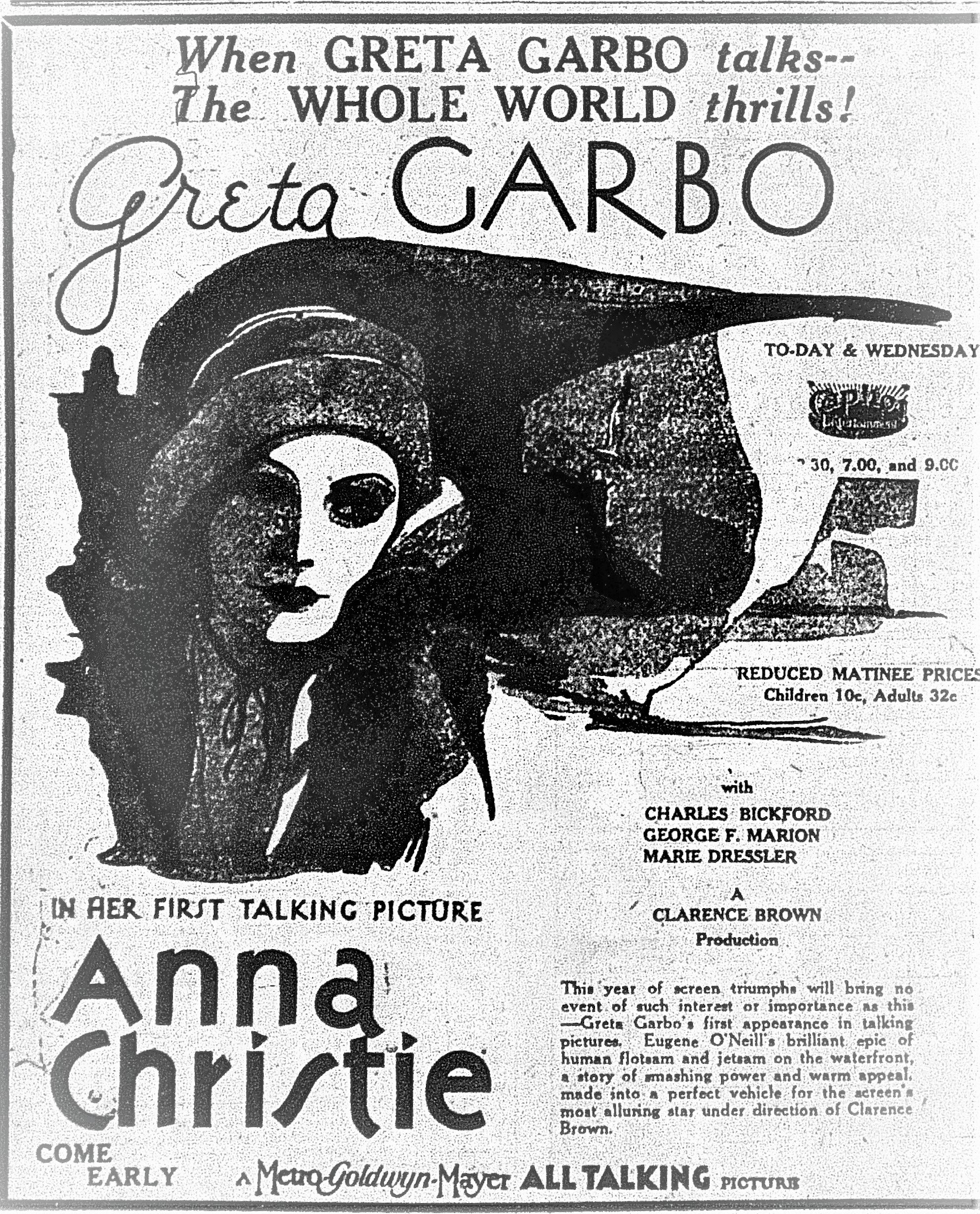

Examiner, Dec. 4, 1929, p.13. Despite the coming of sound, in this MGM film, released in July, Garbo herself remained silent — she was apparently still trying to master English. The movie was released with a musical score and sound effects by Movietone.

Examiner, Dec. 7, 1929, p.13. Lloyd was immensely popular in the 1920s — the shot of him dangling from the clock face of a skyscraper in Safety Last (1923) is a classic image — but, like another silent great, Buster Keaton, proved to be less successful with the coming of sound.

The zippy, dance-happy, extravagant, investment-rich, and optimistic years of the 1920s ended abruptly. On Oct. 29, 1929, the stock market crash marked the beginning of a decade of capitalist failure, massive unemployment, general depression, rising fascism, and a long march to war – or, as one writer put it, “a troubled, darkening decade, lurching towards explosion.” The city’s two remaining movie theatres, the Capitol and Regent, managed to survive those harsh years — they lowered their prices, made all sorts of special offers, and introduced double features to draw in the patrons. They also complemented film offerings with live performances harkening back to the days of silent screenings.

Going to the movies was one of the more “affordable amenities,” and, indeed, was at least partially a way of taking a few hours off from the troubles. Not so many people ventured out to the more expensive offerings of the Grand Opera House, which no longer showed motion pictures and opened its doors less and less often for stage attractions. As the decade went on, when the Grand did have “shows,” they were usually local performances.

The Marx Brothers finally show up — over and over again

The Marx Brothers did come to town — on screen — and with their unique brand of anarchic humour did their best to puncture holes in social strata balloons (mocking the rich and in general running amuck).

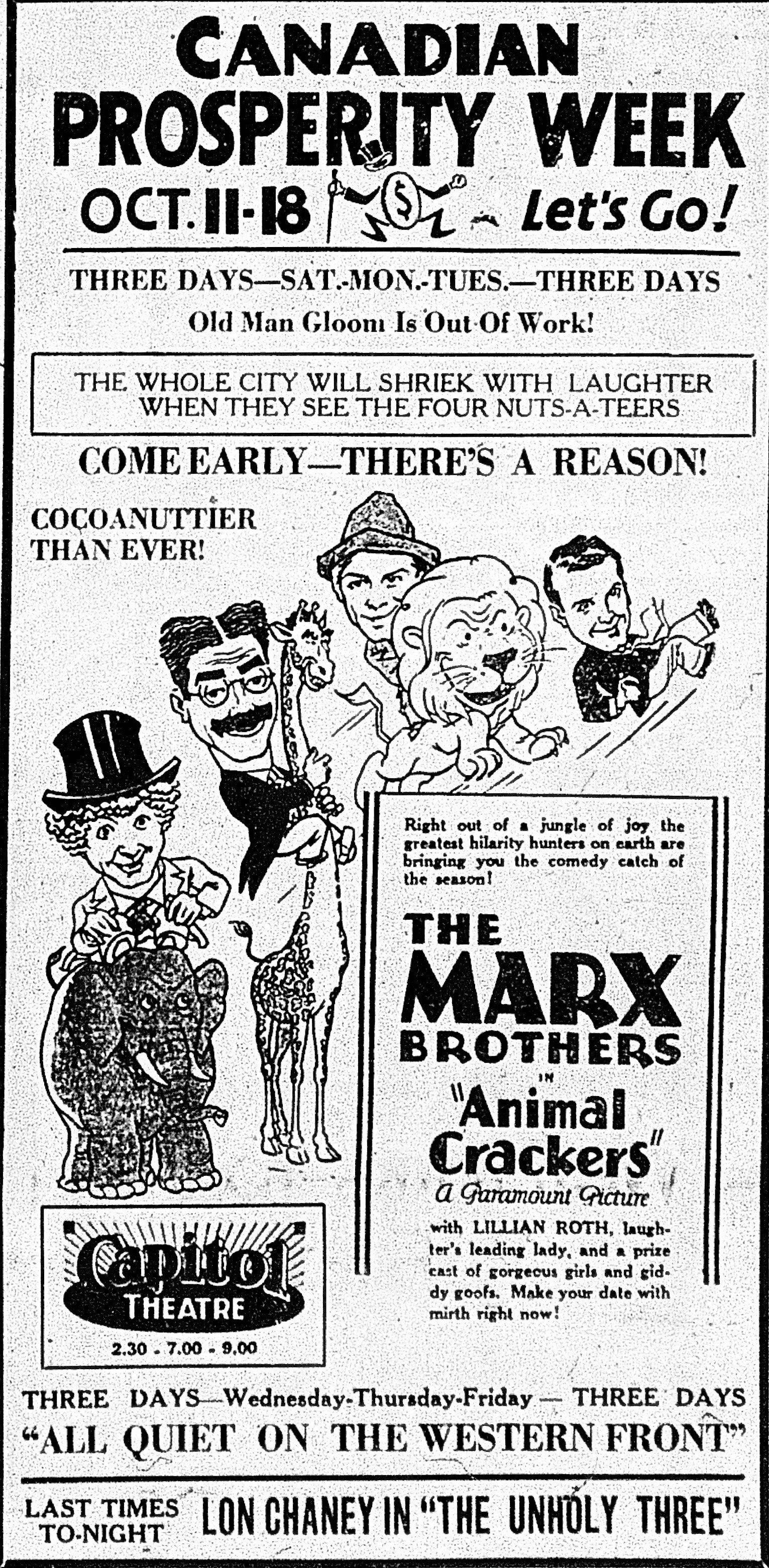

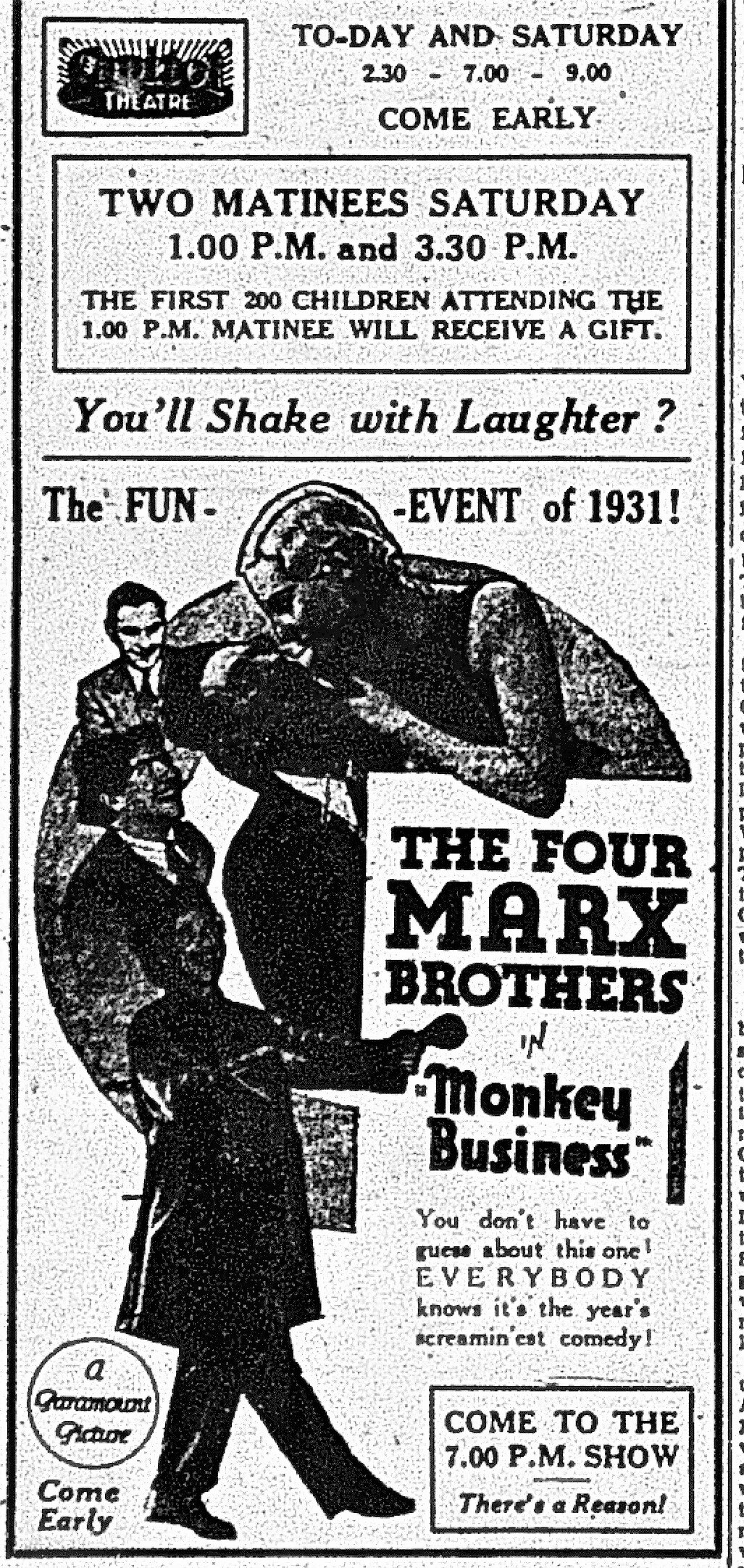

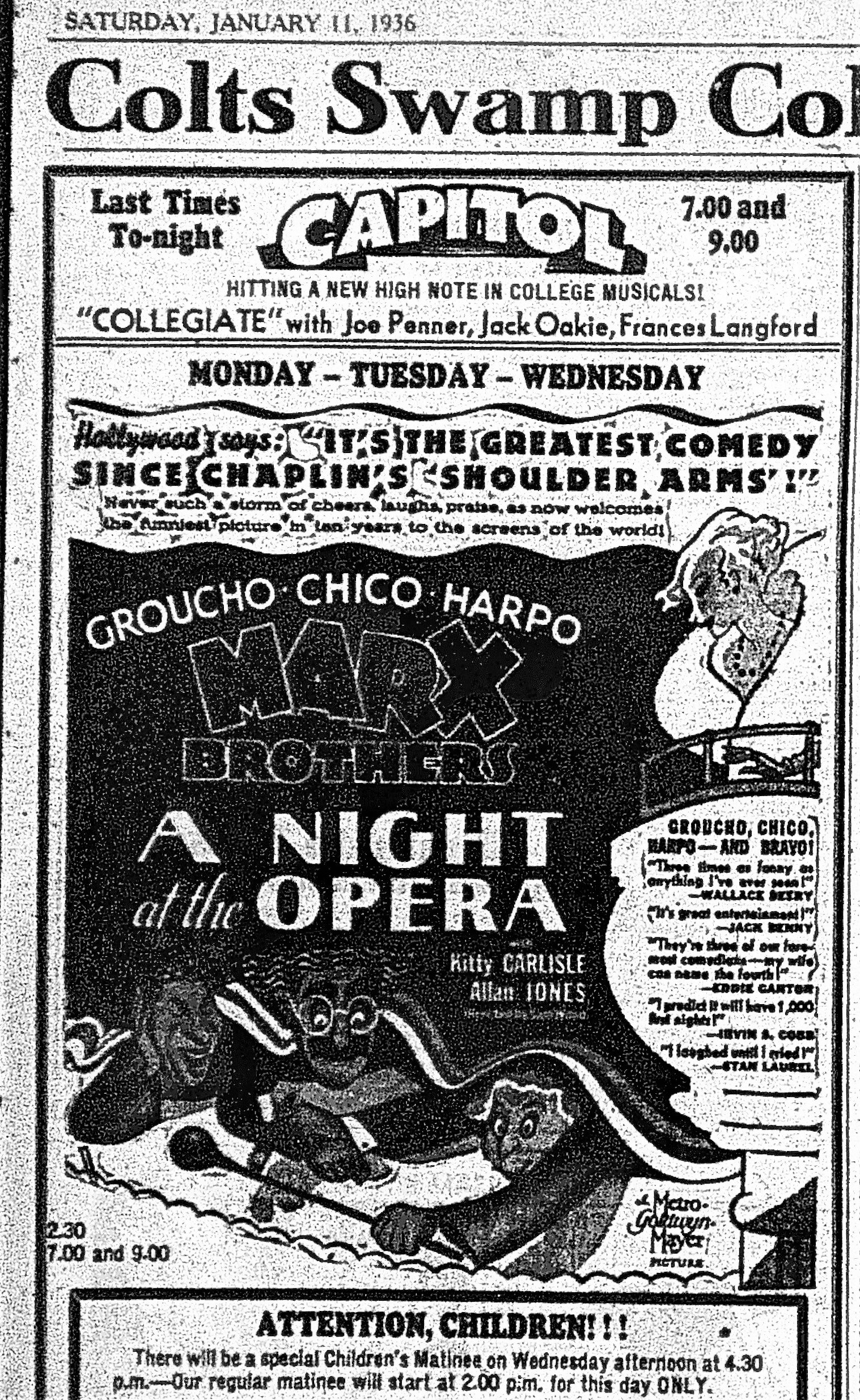

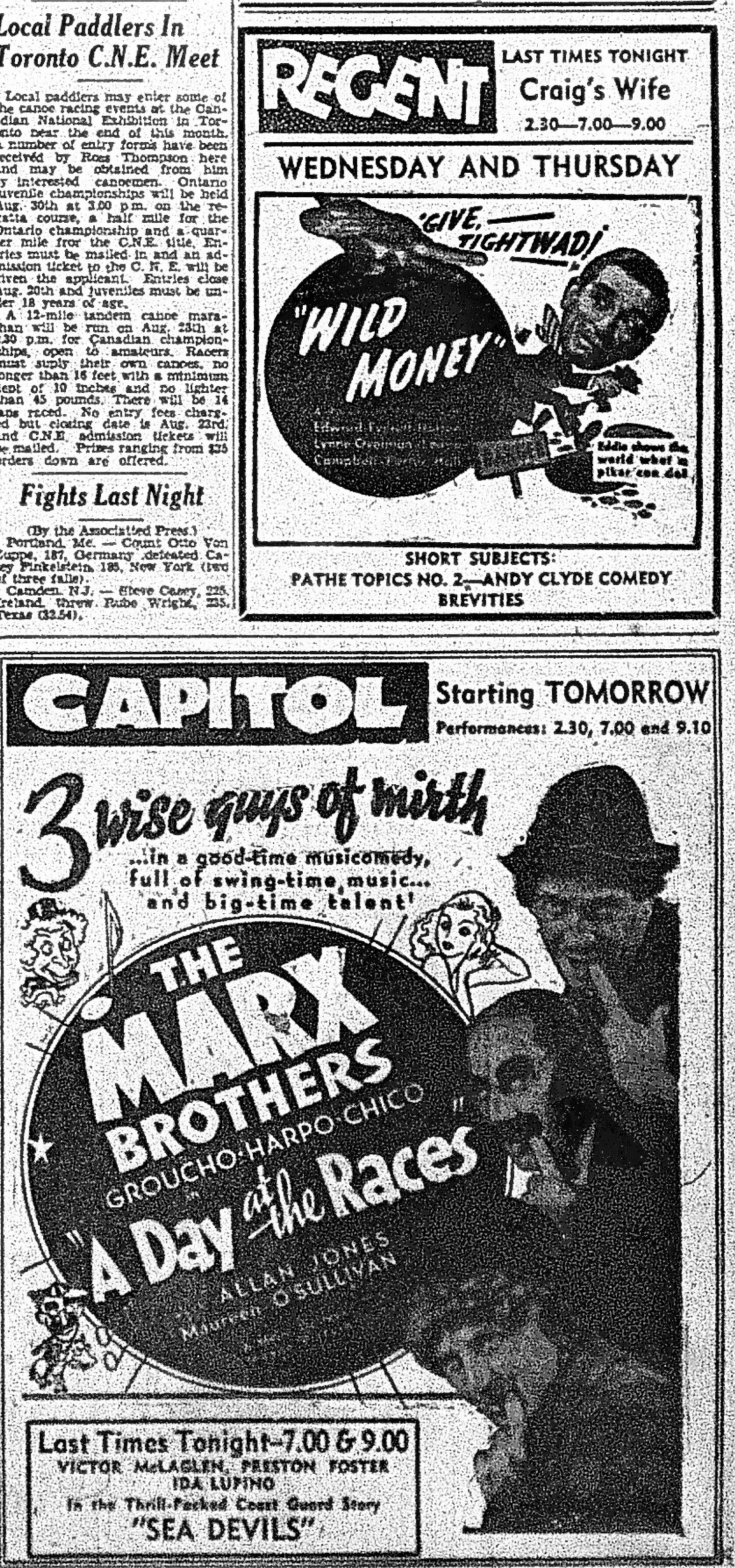

The Marx Bros, from left to right: Examiner, Sept. 11, 1929, p.1; Examiner, Oct. 10, 1930, p.17; Examiner, Oct. 23, 1931, p.17; Examiner, Jan. 2, 1934, p.9.

The Capitol broke box-office and attendance records with the screening of the Marx Brothers’ second film, Animal Crackers (1930), over three days in October 1930. Immediately after that, the anti-war All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) did almost as well (the second-largest business ever). When Duck Soup (1933) screened at the Capitol during the frigid weather of January 1934, Jeanette wrote, “The atmosphere of foolery never lets up.”

Left: Examiner, July 15, 1932, p.15. Middle: Examiner, Jan. 11, 1936, p.9. Right: Examiner, Aug. 17, 1937, p.13.

Symbiotic relationships: ads — pushing more than simply motion pictures

Motion picture studios had their stables of “stars,” and in ads women as consumers of both movies and beauty products were a prime target.

Examiner, Sept. 23, 1929, p.2.

Examiner, Sept. 16,1930, p.11.

“We want to talk to all our Peterboro friends” . . . popular pictures, at reduced prices

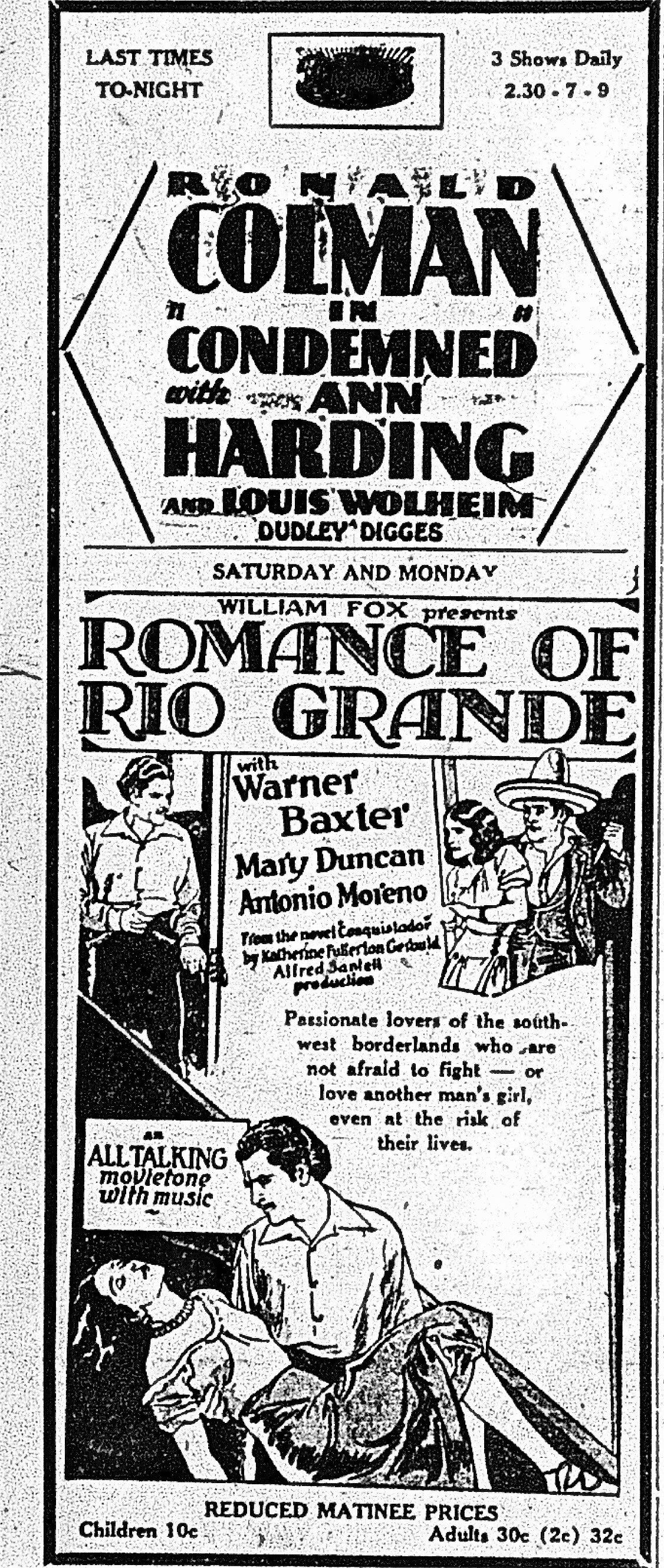

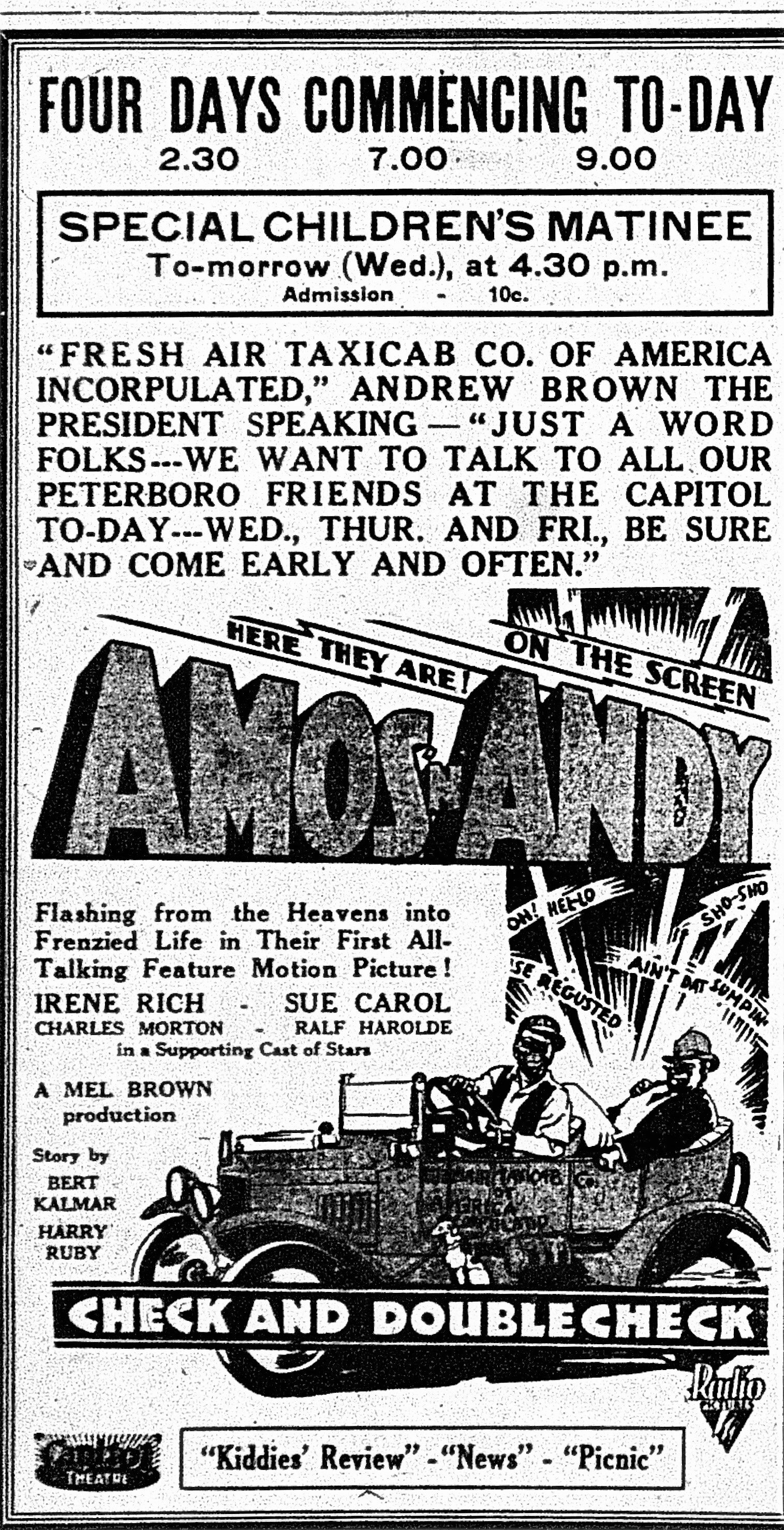

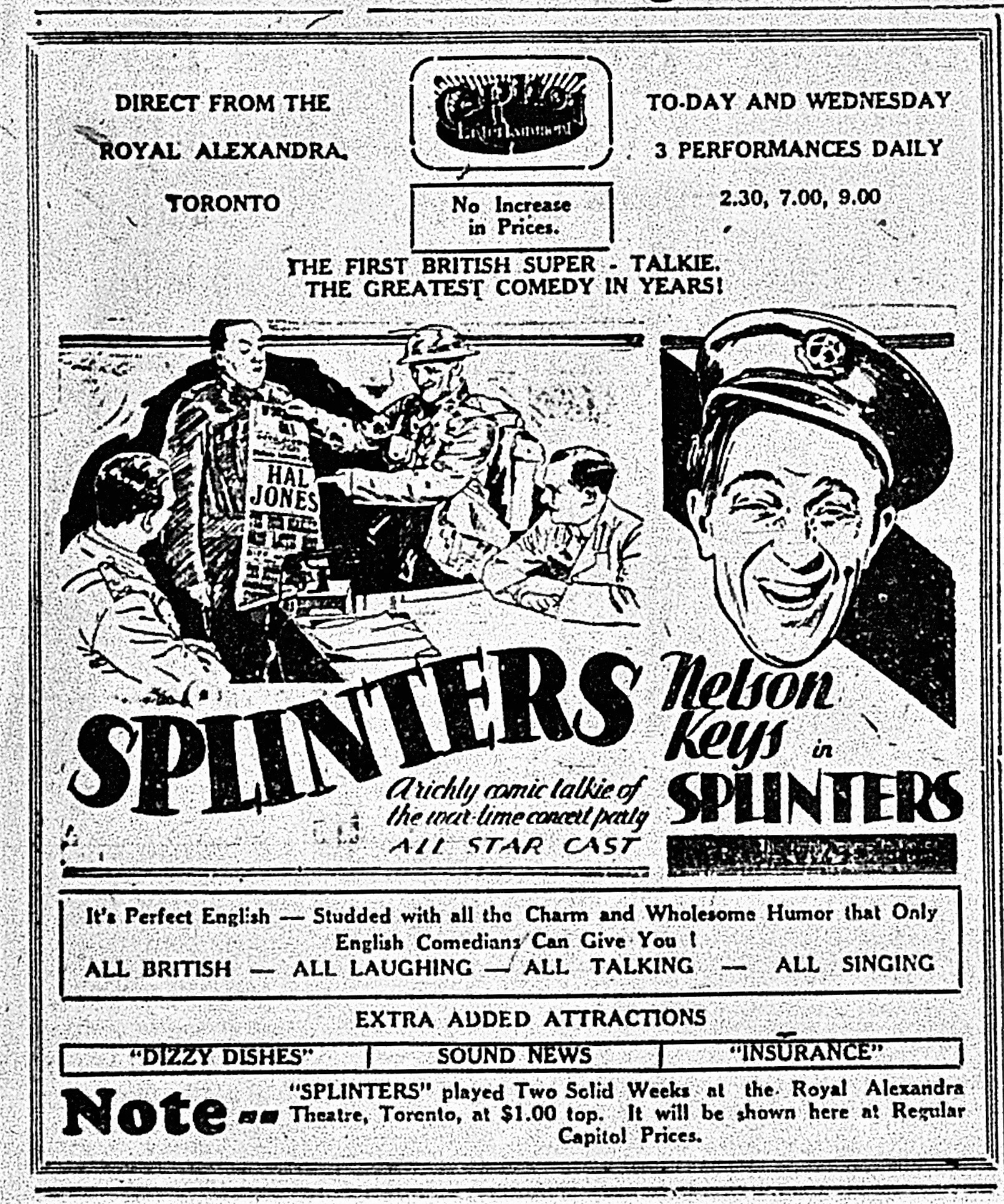

Left: Regent ad, Examiner, June 13, 1930, p.7. Middle: Capitol, Examiner, June 24, 1930, p.9. Right: Capitol, Examiner, Nov. 11, 1930, p.13.

The Regent, reducing prices as of June 1930. The Amos ‘n’ Andy movie Check and Double Check (1930) broke the Capitol’s previous box-office records. Based on the long-running popular radio program, the movie provided a certain continuity and comfort for a local audience nurtured on decades of minstrel shows: it starred two white actors (from the radio program) as African-American characters. But as Jeanette pointed out in a review, the movie included an interlude with a more authentic glimpse of Black culture: “Duke Ellington’s Cotton Club band, a group of well-known musicians who include a left-handed trumpet player in their midst and who play in a manner calculated to thrill the blood of every jazz-lover in the audience.” Duke Ellington would return now and again in the movies — but also live and on stage at Peterborough’s Club Aragon on June 4, 1949.

Left: Examiner, Sept. 2, 1930, p.9. Splinters (1930): A rare British picture among the usual Hollywood fare.

Middle: Examiner, April 7, 1931, p.13. Just Imagine (1930): What on earth would things be like in 1980? An imaginary look at both past and future, which concludes that “You’ll find more laughs in 1980” than in 1890. The Fox studio apparently tried out the new back-projection technology in this film. You can watch it on YouTube.

Right: Examiner, Jan. 22, 1931, p.21. Under Suspicion (1930): An even more rare film — said to be a “Canadian-made drama,” but produced by the U.S. Fox company. Still, it was notable not just for being produced in colour but for being the first sound film with exterior scenes shot in Canada, in Jasper, Alberta.

Community relief projects, connecting local commerce, and mid-nite shows for fun and frolic

Left: Examiner, Dec. 10, 1930, p.13. A year into the Depression, the movie theatres were joining with community efforts to raise funds for unemployment relief and other causes. These benefits became standard events during the following years.

Middle and Right: Examiner, Dec. 30, 1930, p.13. Bringing in the new year at the theatres also became a regular feature.

Examiner, Nov. 28, 1930, p.18. A full-page spread connecting the show at the Regent Theatre to local merchants, restaurants, and even a dance hall or two — all built around the Eddie Cantor movie Whoopee, playing for a full week. The Schneider Brothers (with their ad at top left) were co-owners of the Regent. Note Austin’s Dining Room with its “dime a dance” offer. A song by the popular Ruth Etting, “Ten Cents a Dance,” was released that same year. Doris Day played Etting in Love Me or Leave Me, with James Cagney (1955).

Whoopee, shot in two-strip Technicolor and Busby Berkeley’s first as a choreographer, included Cantor (a vaudeville and Broadway star in his first feature-length movie) appearing as a black-face minstrel. It’s worth noting how time after time, from the 1920s to the 1940s, white actors playing lead roles, from Al Jolson to Eddie Cantor and on, applied blackface; when Black actors appeared in films they tended to play roles as minor (and often comical) characters.

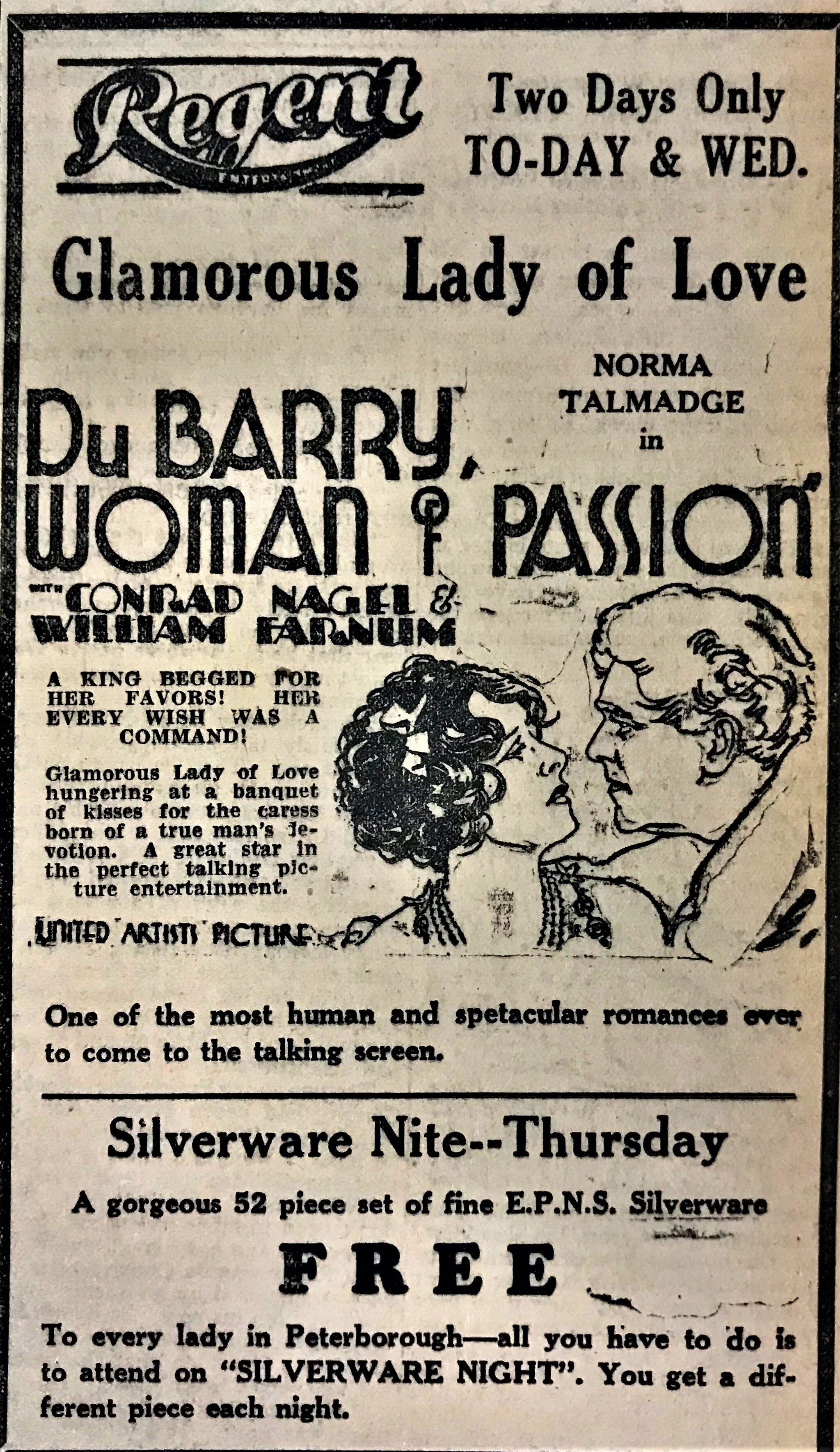

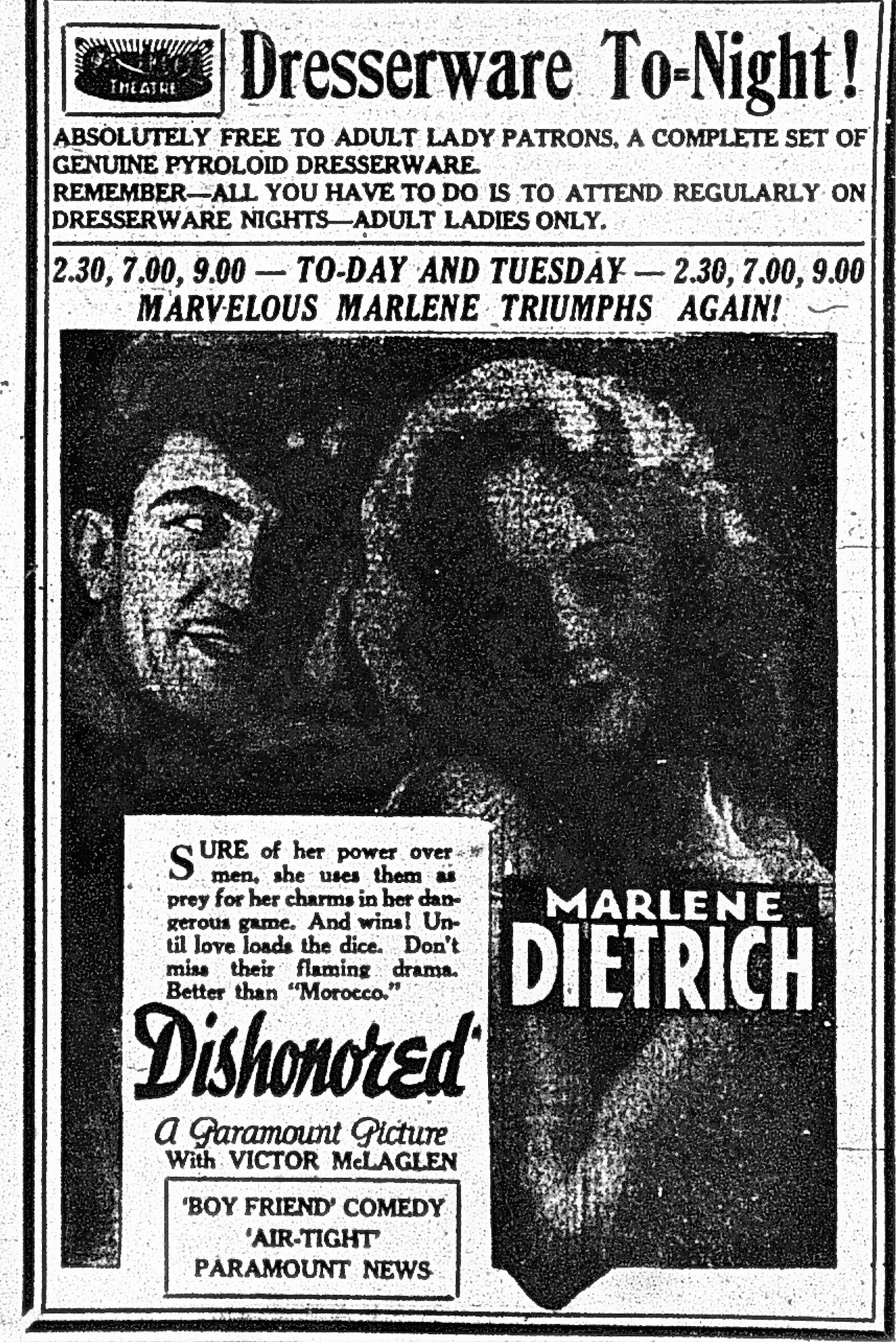

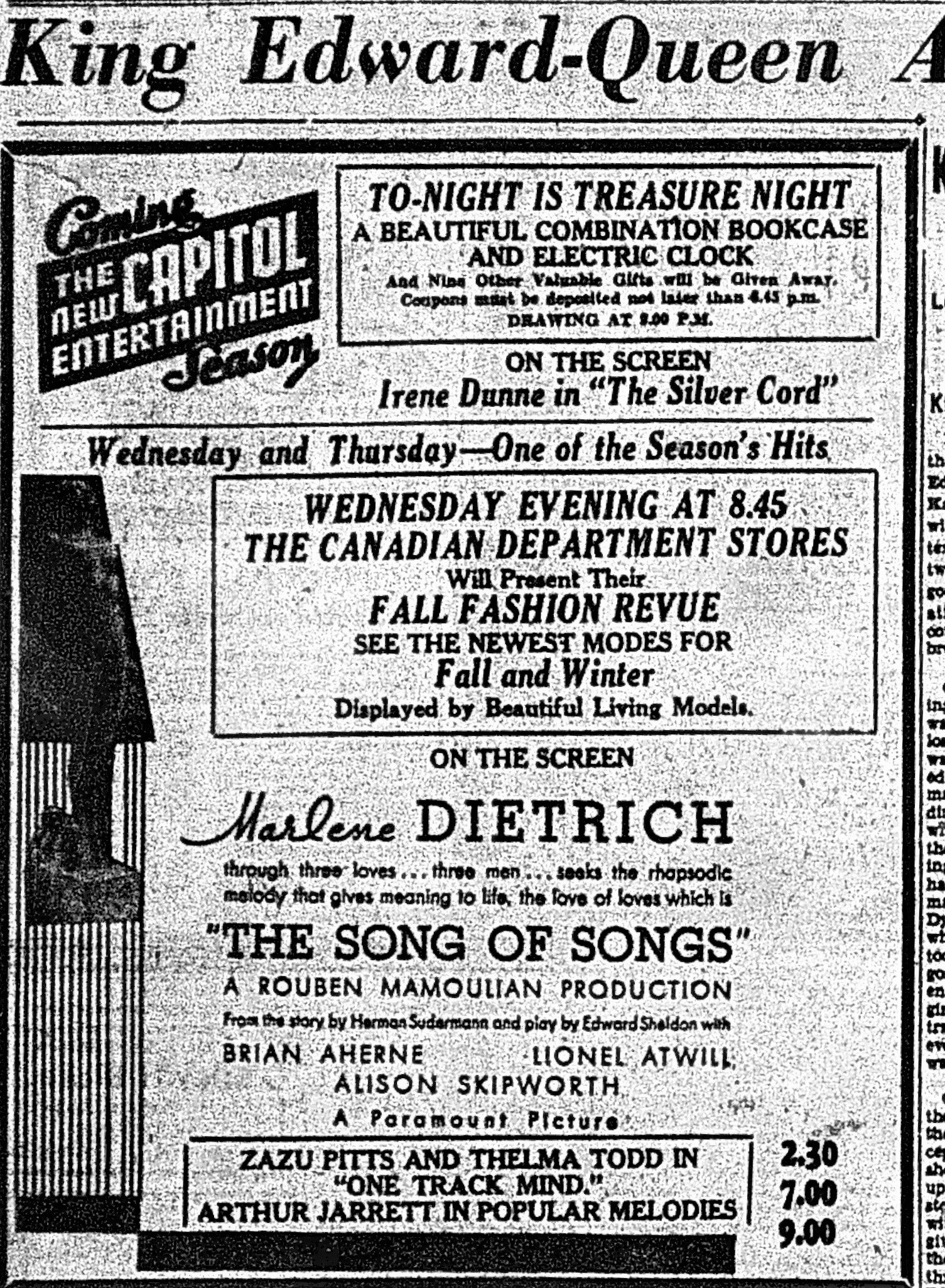

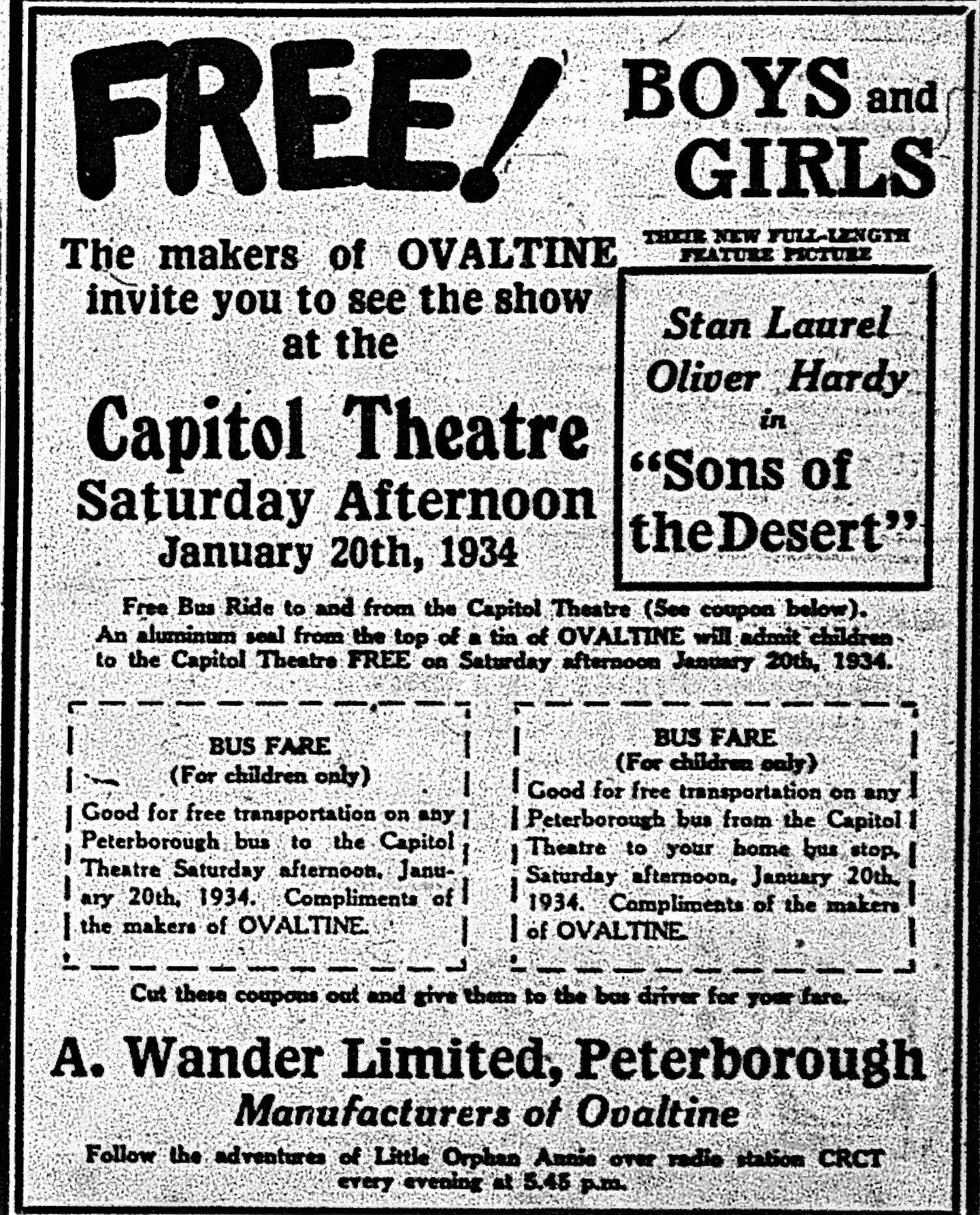

Silverware, dresserware, and community tie-ins: adults and children

Left: Examiner, July 7, 1931, np. Middle: Examiner, May 11, 1931, p.13. Right: Examiner, Sept. 28, 1933, p.9.

Silverware, dresserware, and treasure nights: in the midst of a depression you could get a lot just by spending a few cents and going to the moving picture show. The Capitol also forged a commercial relationship with Canadian Department Stores, which in November 1932 moved from its previous location at 361-365 George Street to a new building on the south-west corner of George and Charlotte — which eventually adopted the name of its owner, Eaton’s.

Examiner, Jan. 27, 1933, p.13. The Regent bonds with a local manufacturer.

Examiner, Feb. 29, 1936, p.12. The Capitol and Canadian Department Stores. In the 1930s, most everyone wanted a big radio console.

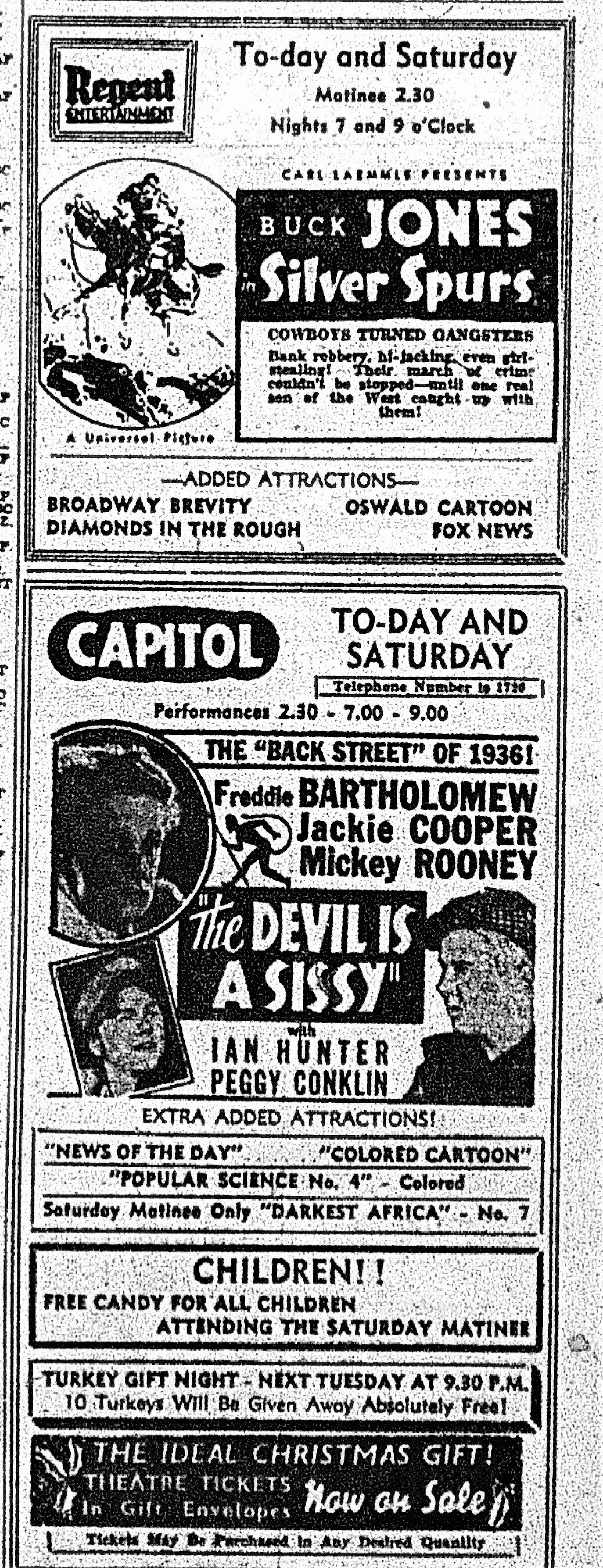

Left: Examiner, Jan. 16, 1934, p.10. Middle: Examiner, April 4, 1936, p.13. Right: Examiner, Dec. 18, 1936, p.13. Again, a corporate tie-in with a local manufacturer, and special times for children. Free admission if your parents bought a tin of Ovaltine, and free bus fare. Free candy at a Saturday matinee. Plus turkey gift nights for adults — and you got to see the movies!

Examiner, Sept. 30, 1935, p.9.

Motion Picture Herald, Jan. 18, 1936, p.82.

The Capitol’s well-known manager, Jack Stewart, went all out to draw attention to Redheads on Parade. The Motion Picture Herald, out of New York and Chicago, took note and published a photo of the window (above) in its Jan. 18, 1936 issue. Apparently the film needed all the help it could get. One of far too many musicals in the “backstage movie” genre – a picture about picture-making – it received bad reviews and was something of a flop.

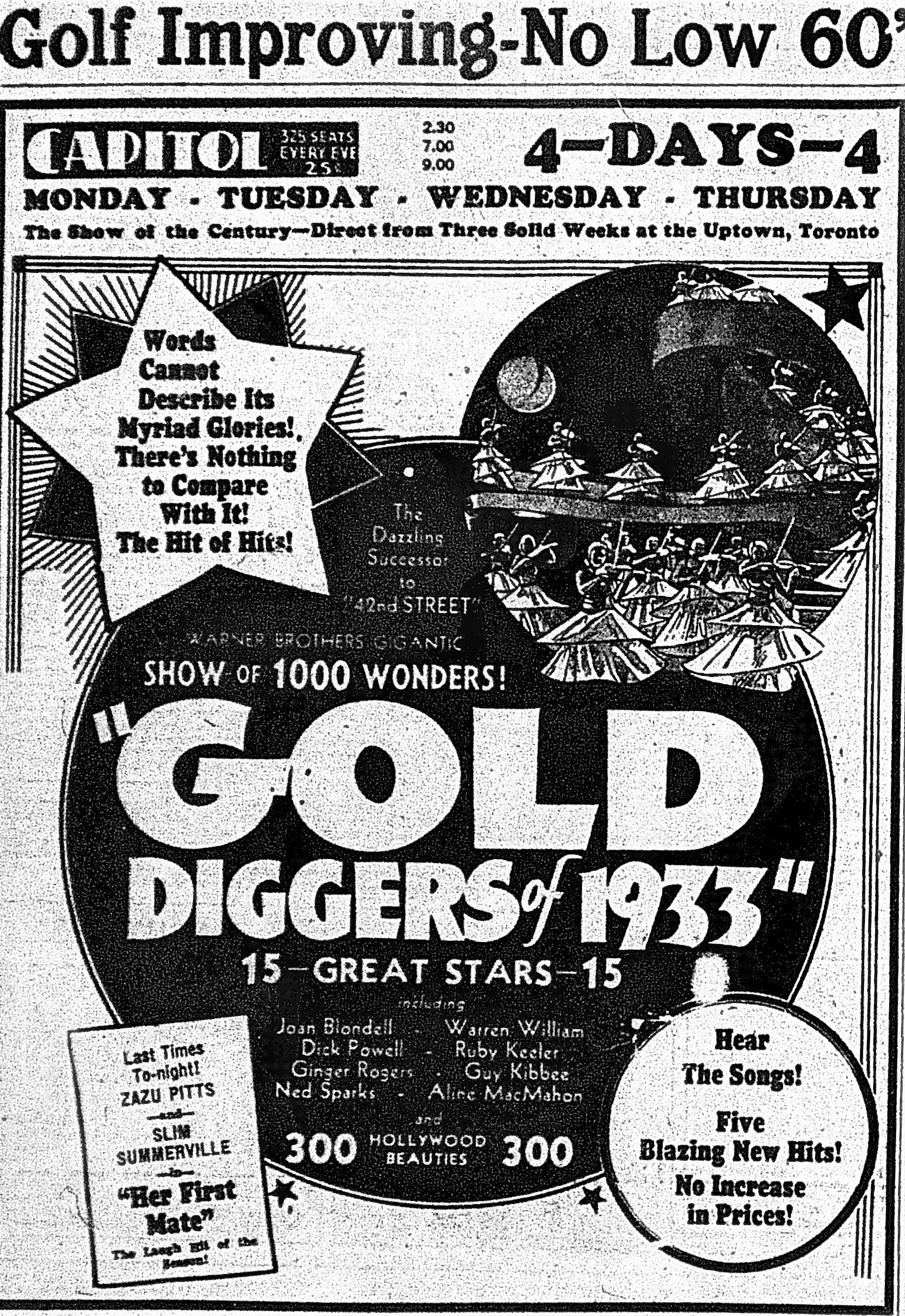

The musicals make a comeback with Gold Diggers

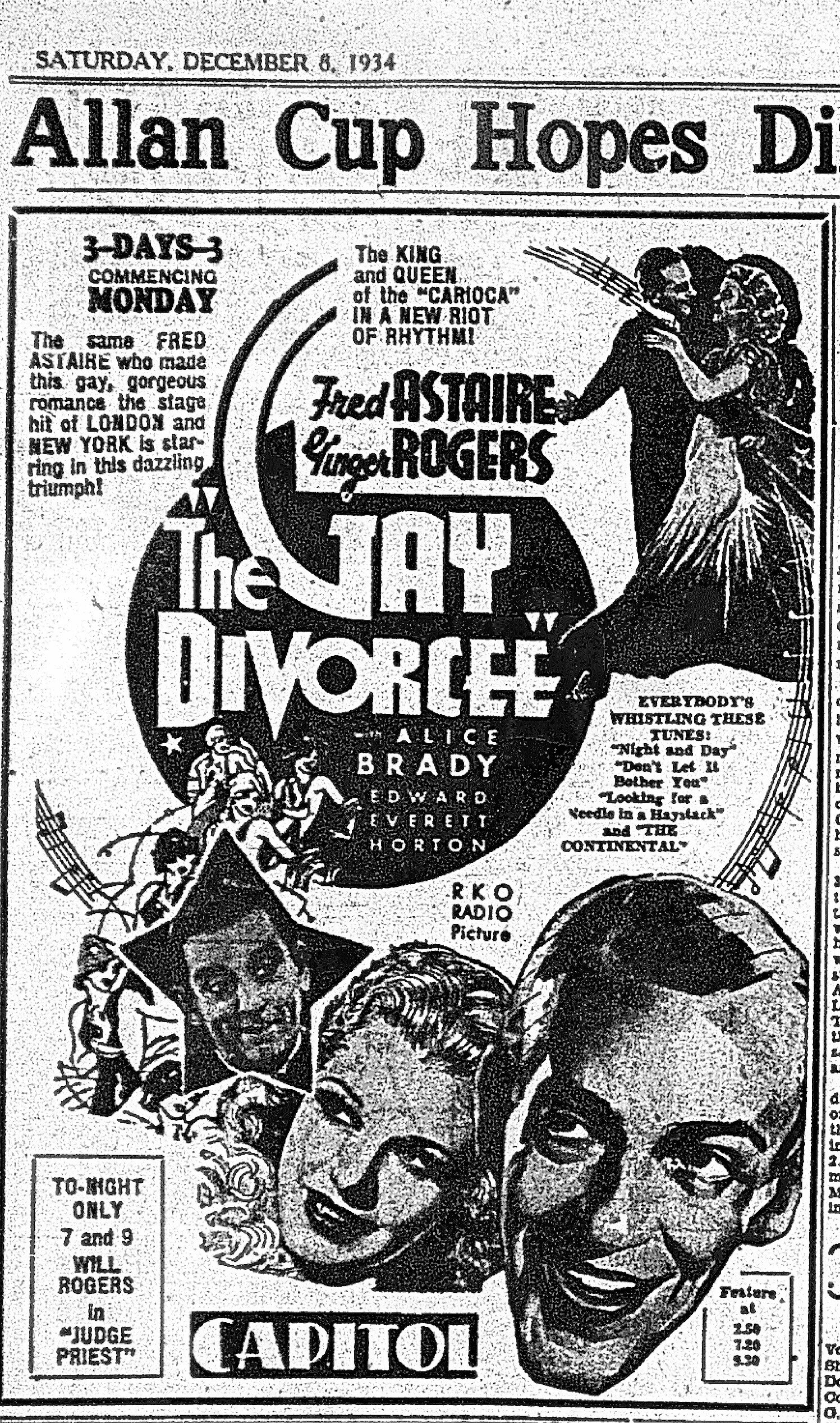

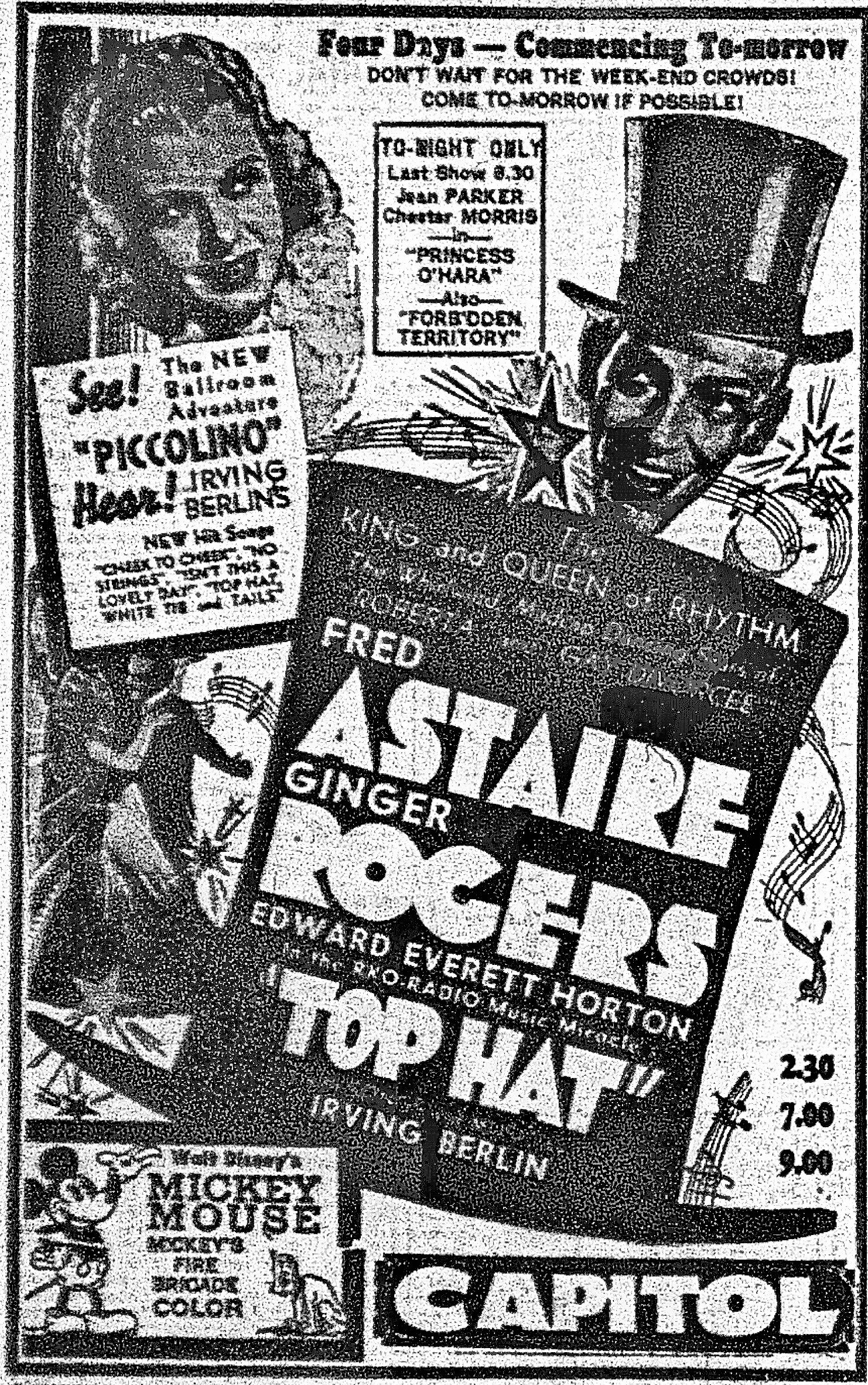

But the backstage music was a genre unto itself in the 1930s, and many of them proved immensely popular. Perhaps the most notable was Gold Diggers of 1933 — so successful that it was followed by Gold Diggers of 1935 and 1937. And then along came Astaire and Rogers, not to mention Mickey Mouse.

Left: Examiner, Aug. 19, 1933, p.12. Middle: Examiner, Dec. 8, 1934, p.13. Right: Examiner, Oct. 8, 1935, p.9.

In Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Gold Diggers of 1933 — a quintessential depression movie — is on the screen when the outlaws seek refuge in a theatre after a shooting.

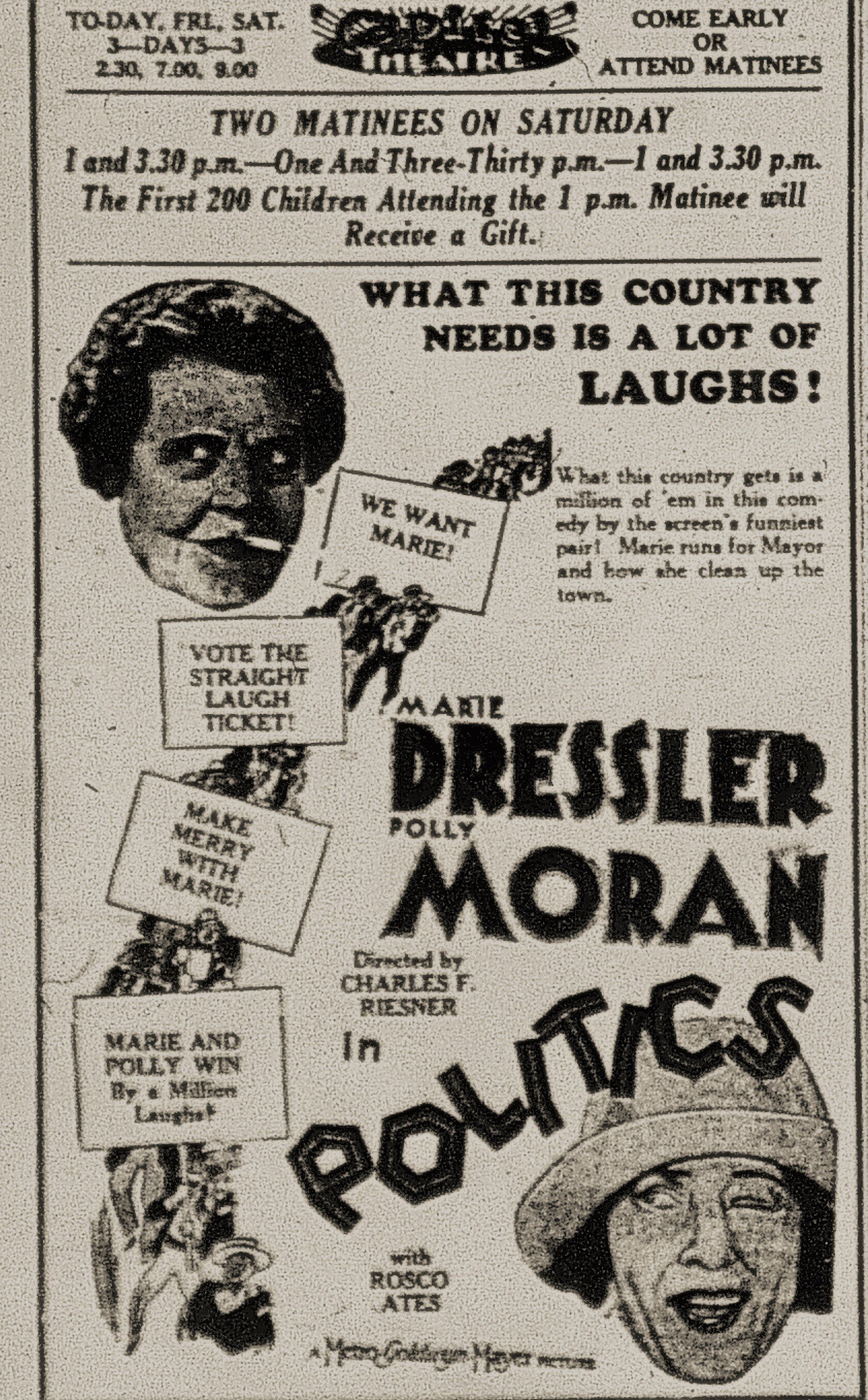

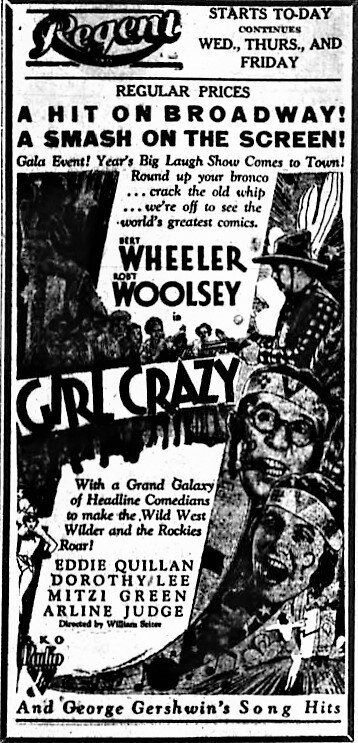

Comedies — and especially Marie Dressler — are most popular

Left: Examiner, Sept. 3, 1931, p.13. Middle: Examiner, Oct. 20, 1934, p.13. Right: Examiner, Oct. 25, 1932, p.17.

Capitol manager Jack Stewart said that of all the various film genres, comedies were the most popular in Peterborough. Cobourg’s “big, rough Marie Dressler,” Jeanette wrote, was a “gallant old war-horse,” with “wonderful inflections in her hoarse, low voice.” The movie Politics (1931) exhibited “the same mixture of smiles and tears and dogged, indomitable courage in a desperate situation that has made the name of Marie Dressler a household word.” Speaking of the popular comedy team of Bert Wheeler and Robert Woolsley in Girl Crazy (1932), Jeanette said: “The audience at the Regent last night laughed almost constantly at the antics of the two and their companions . . .”

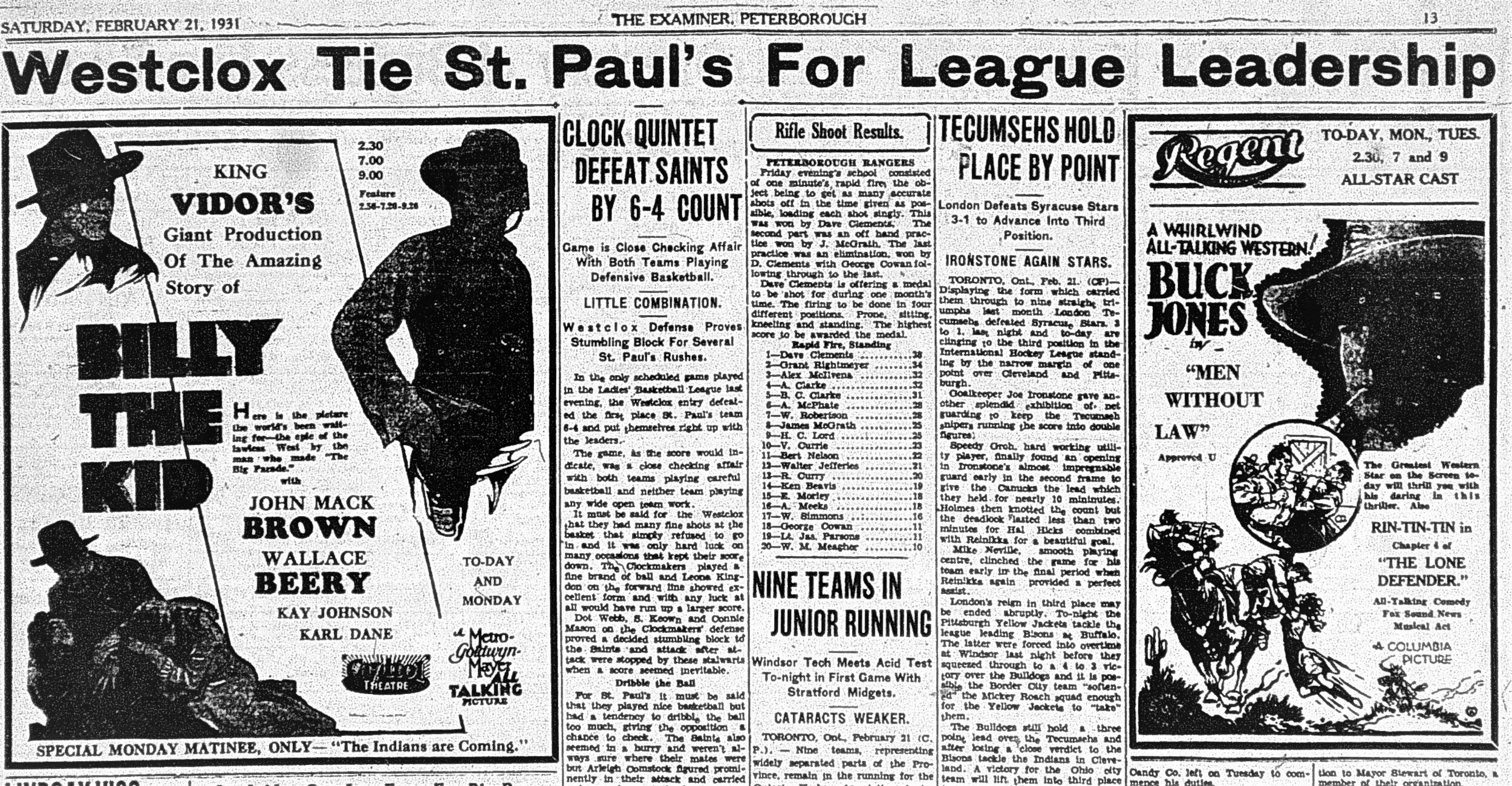

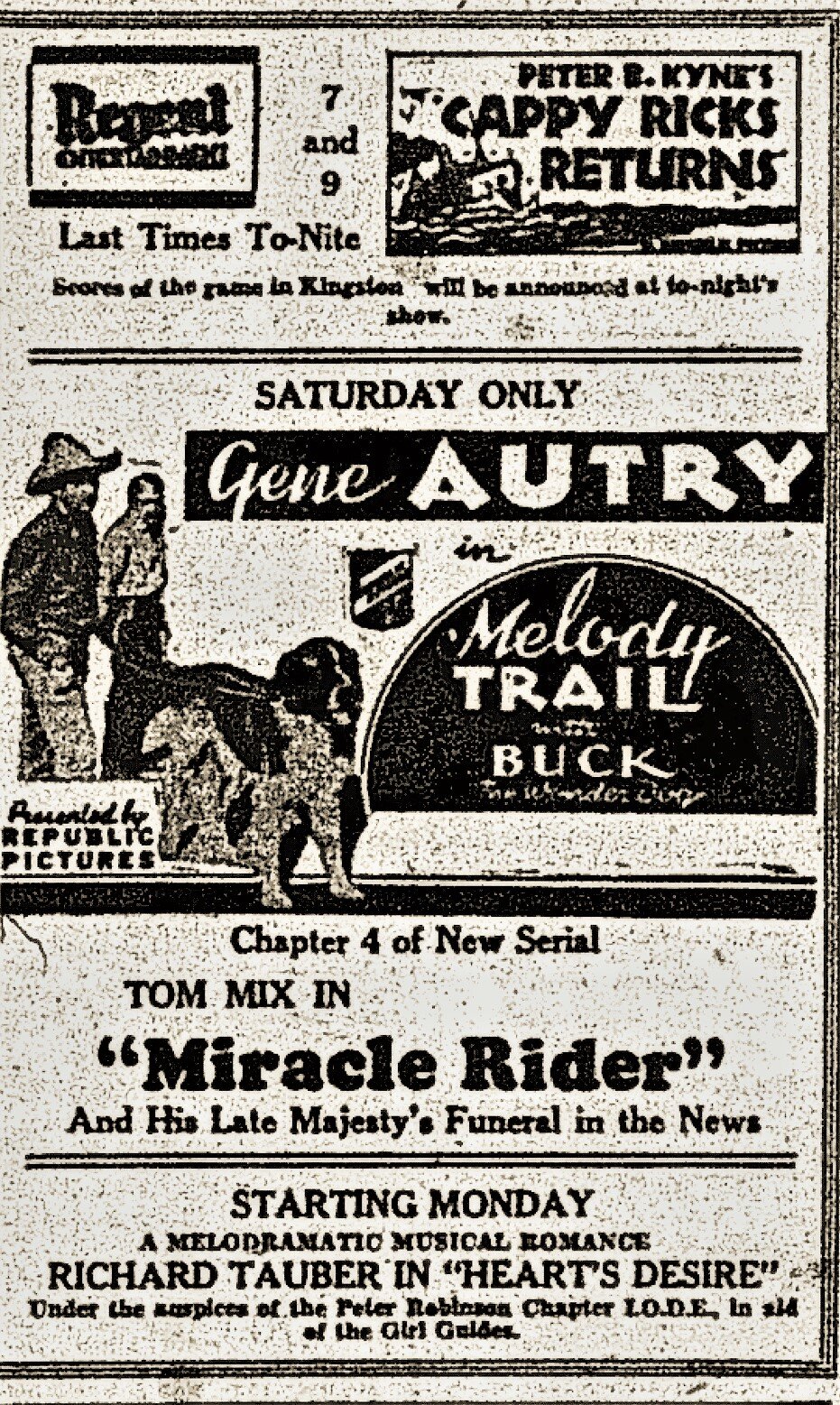

The cowboys never do completely ride off into the sunset

Examiner, Feb. 21, 1931, p.13.

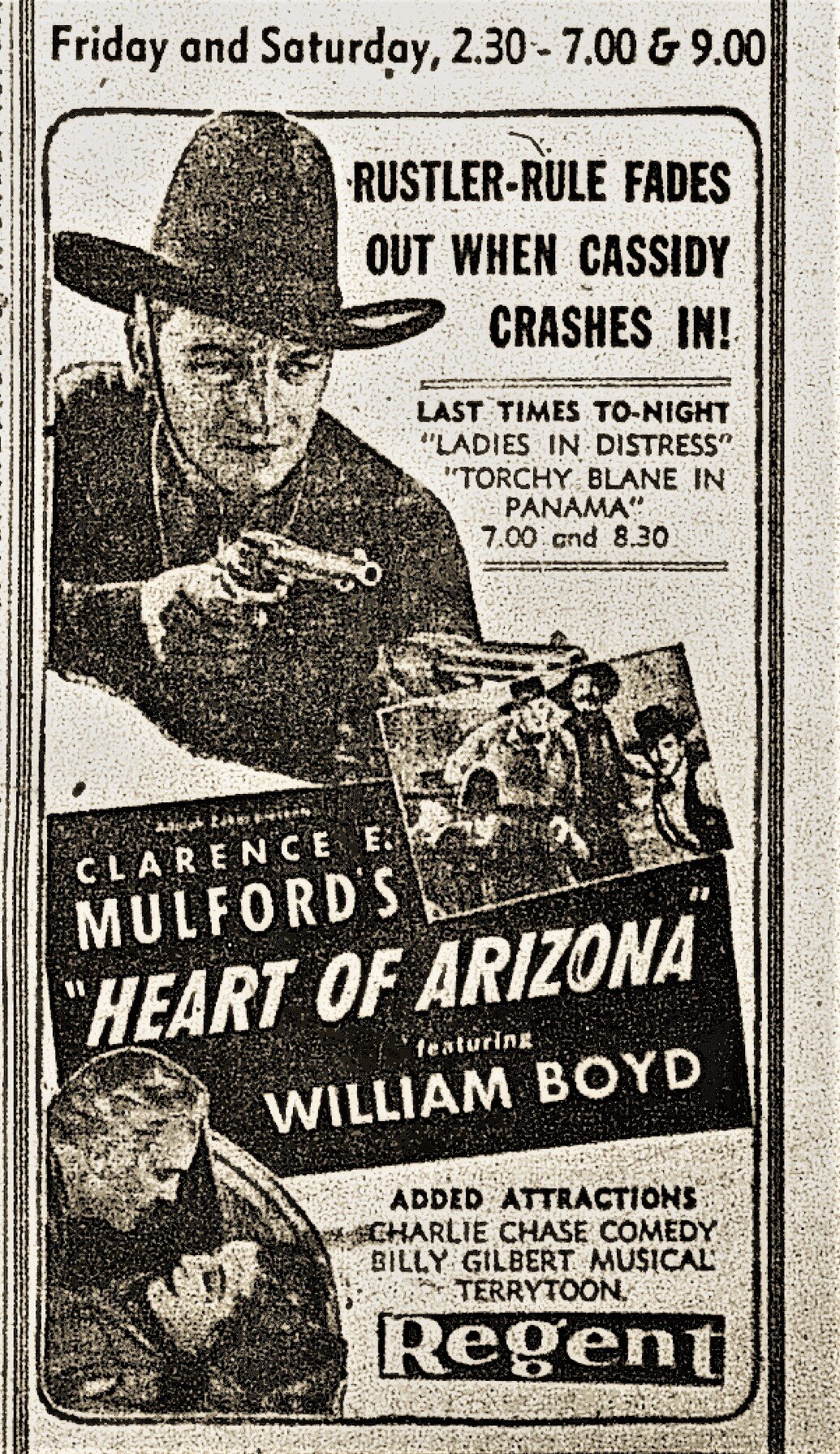

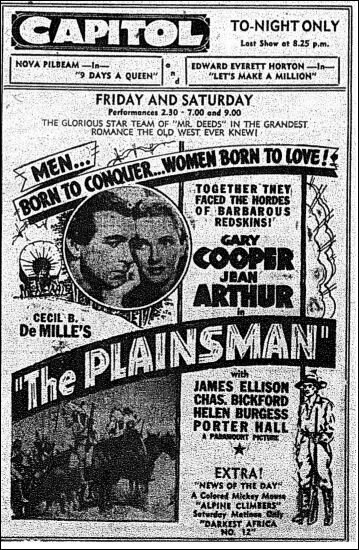

Left: Examiner, Feb. 28, 1936, p.13. Middle, Examiner, Oct. 13, 1938, p.9. Right: Examiner, Jan. 21, 1937, p.15.

Western heroes abounded. The Westerns were a mixture of “A” movies (Vidor’s Billy the Kid and DeMille’s The Plainsman, with folksy Gary Cooper) and low-budget “B” movies (Buck Jones, Gene Autry, Hopalong Cassidy, and the Tom Mix serial) — which would become a mainstay of the TV screen in the 1950s.

“A city shrieks in horror . . .” but has donkey baseball for relief

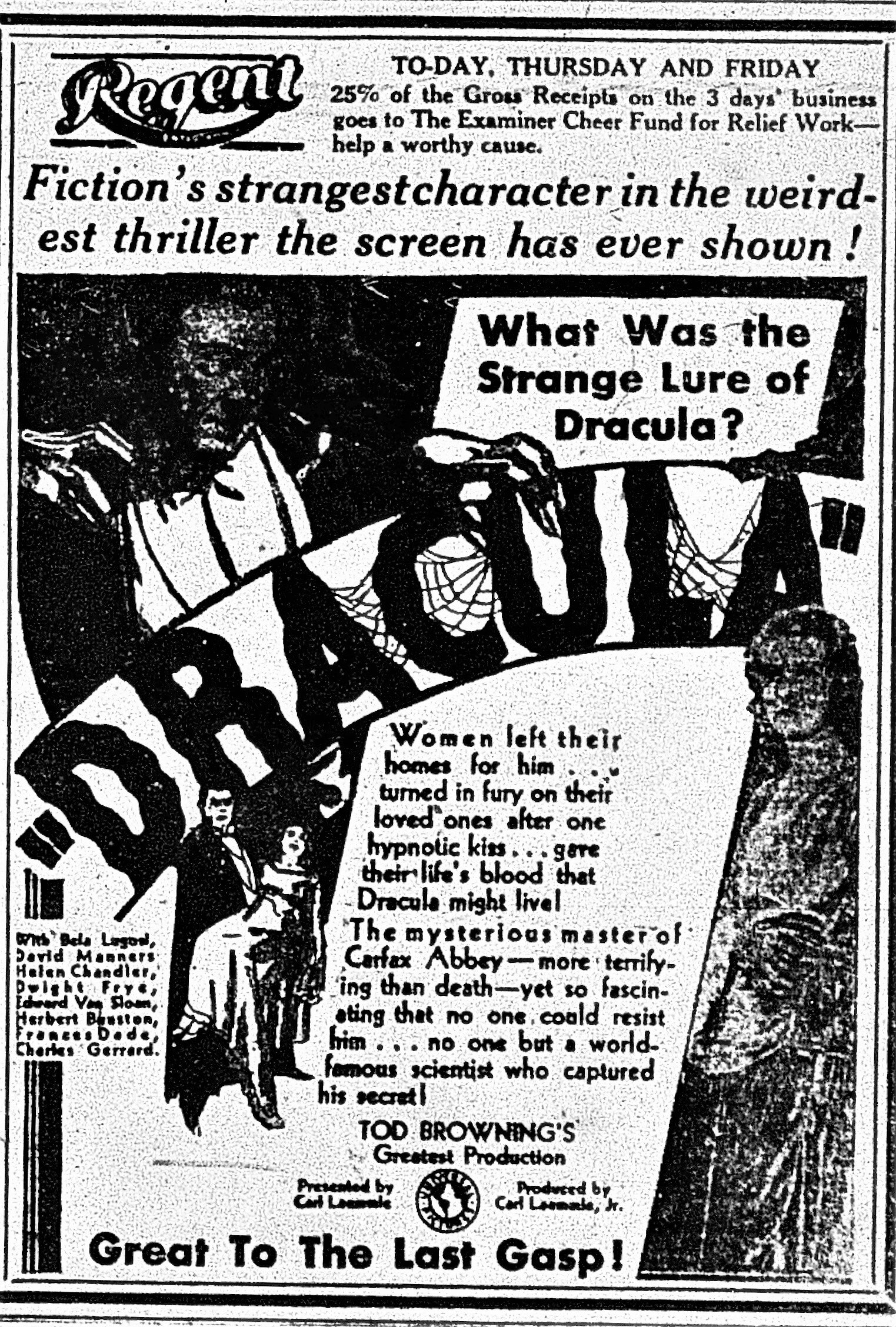

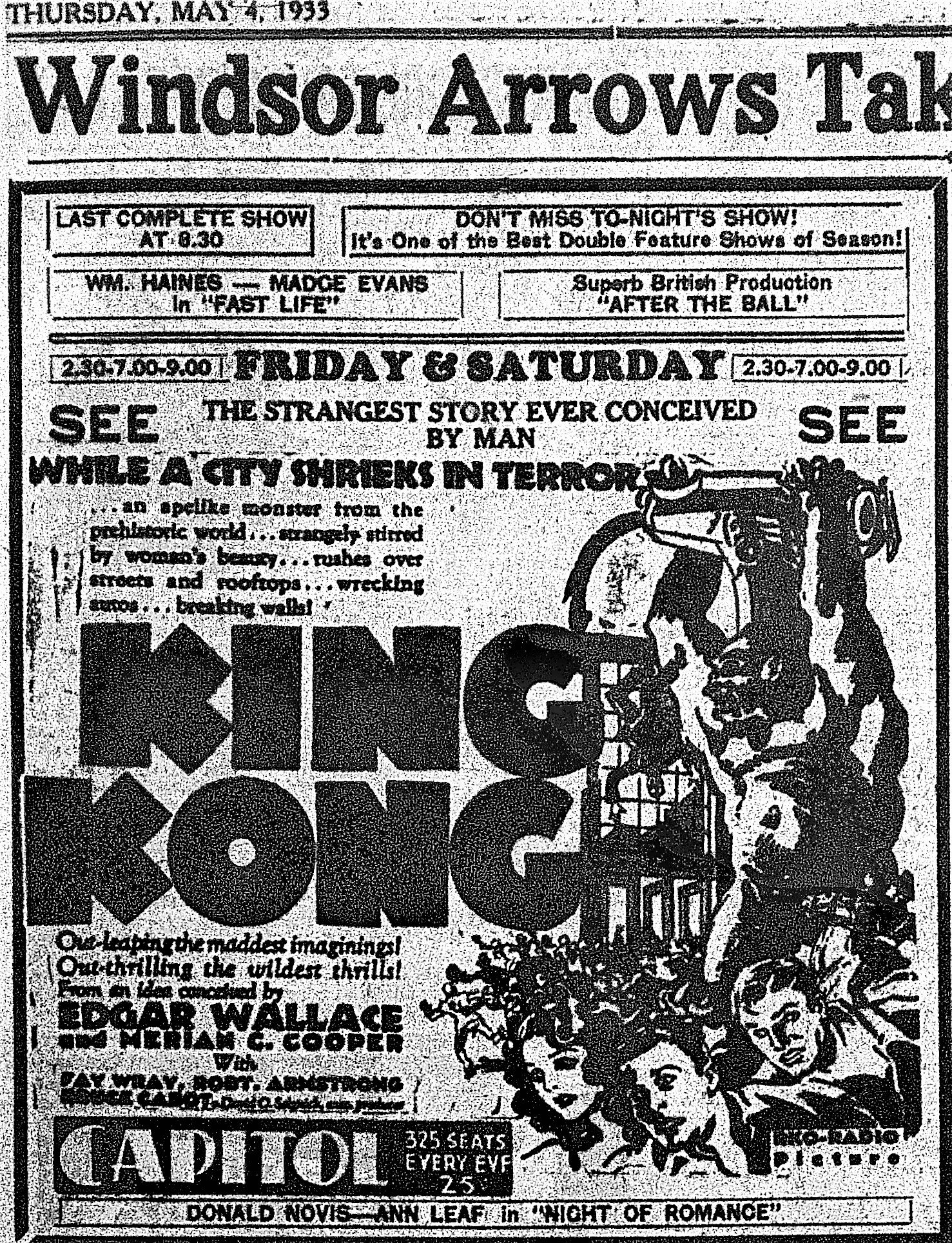

Left: Examiner, April 29, 1931, p.13. Middle: Examiner, May 4, 1933, p.17. Right: Examiner, July 27, 1935, p.13. For added enjoyment, “Donkey Baseball,” among other shorts. And later on, donkey baseball would ignominiously appear live on city playing fields at charity events.

Peterborough’s Murray Paterson reminisced: “We saw some pretty scary individuals on the screen in those days. I remember having the creeps for about a week after seeing a Frankenstein movie. Then there was Dracula, the bloodsucker, and the Wolfman, a normal person who turned into a werewolf when he saw a full moon. I recall coming out of the Regent theatre one cold March evening after seeing a Wolfman film, and as I happened to glance eastward on Hunter Street, guess what I saw. A brilliant, circular, yellow moon just above the horizon. Daaaaaah!”

Left: Examiner, March 17, 1931, p.13. Middle: Examiner, April 4, 1932, p.9. Right: Examiner, May 30, 1936, p.13.

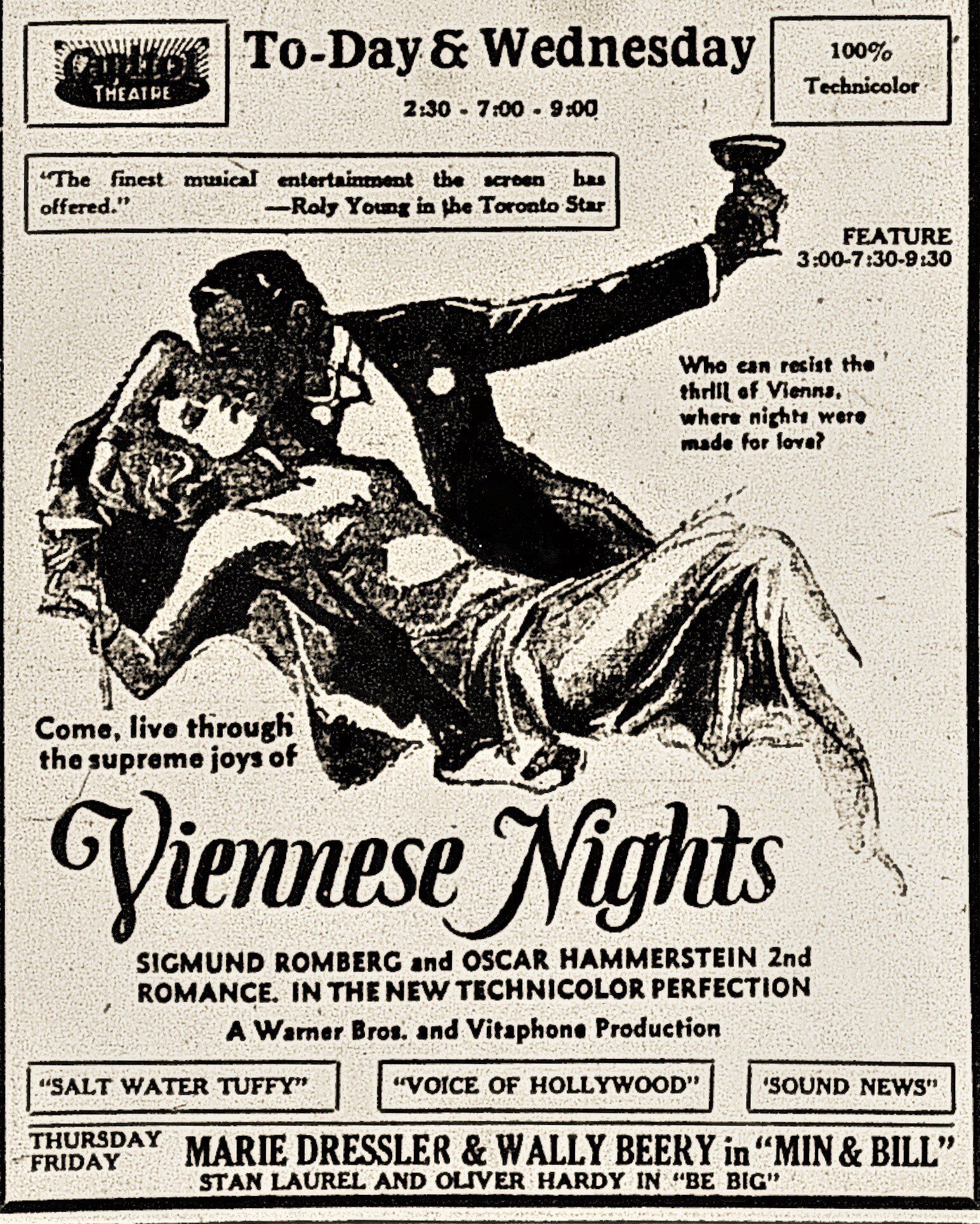

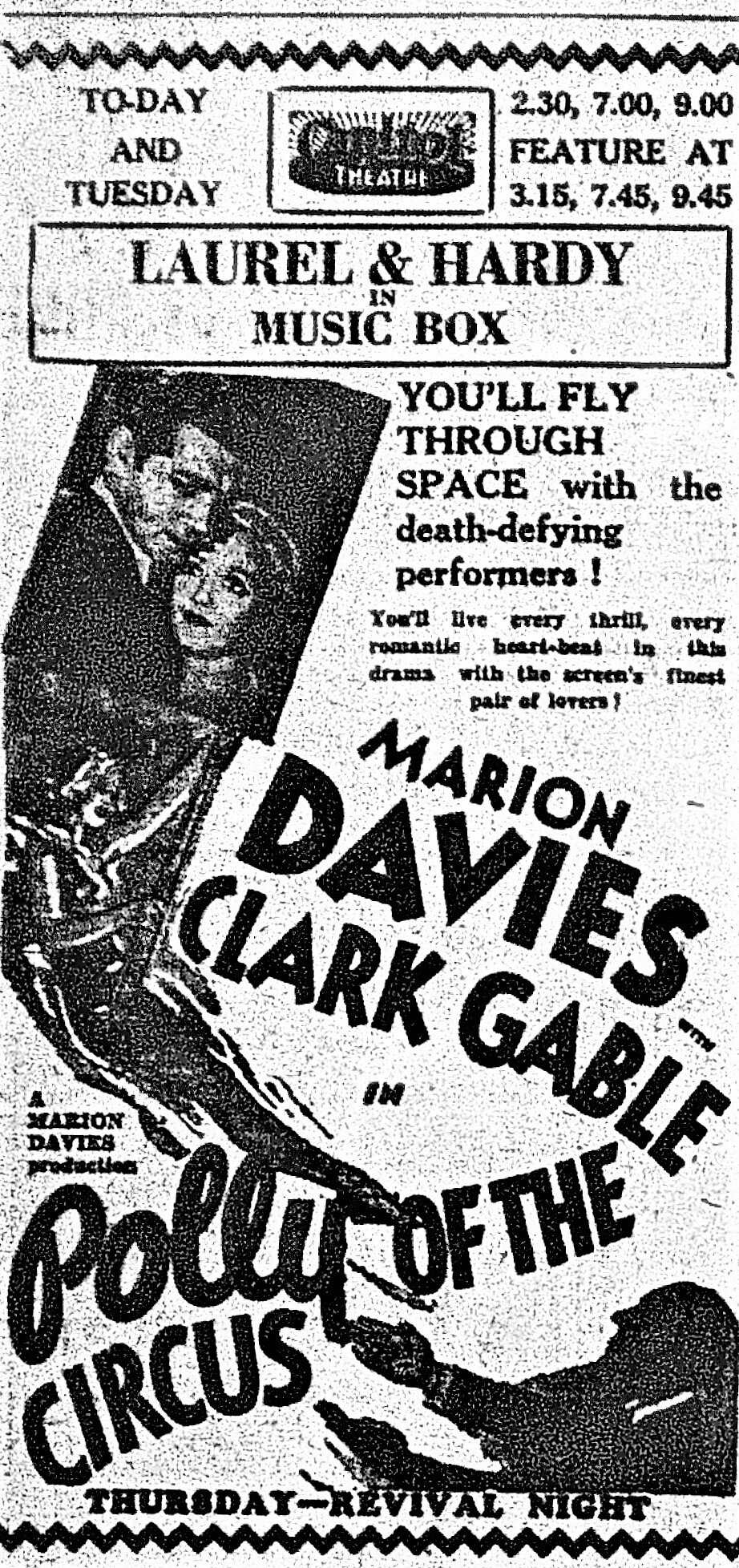

Viennese Nights sports the “New Technicolor Perfection.” Manager Stewart cited Laurel and Hardy — appearing here in The Music Box (1932) — as among the favourites of the Peterborough audience, with an “unfailing following.” Jeanette commented on “The large, exasperated Mr. Hardy and the little bewildered Mr. Laurel . . .” When their film Helpmates came to town in summer 1932 she remarked on how “the dignified stout fellow with the large frame and his whimsically erratic companion with the outsize hat and apologetic demeanor get the very last bit of fun out of this comedy, and the crowd has a side-splitting time with them.”

Shirley Temple . . . and Deanna Durbin . . . and Chaplin remains silent, more or less

Left: Examiner, Sept. 6, 1934, p.17. Middle: Examiner, Dec. 14, 1937, p.11. Right: Examiner, Feb. 16, 1937, p.9.

Shirley Temple: the little big box-office star of the 1930s. Novelist Graham Greene, who wrote film reviews from 1935 to 1939, found himself in a libel suit when he accused 20th Century-Fox “of ‘procuring’ Miss Temple ‘for immoral purposes.’”

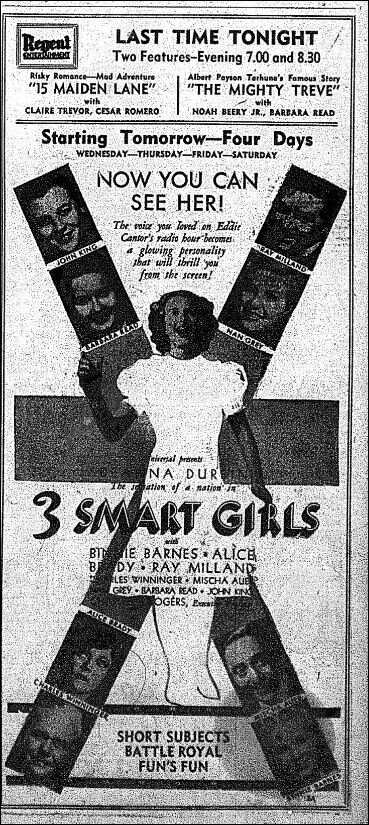

At the Regent in February 1937, the first appearance of another budding star and local favourite: Deanna Durbin. She had a tenuous connection to Peterborough — her parents had lived in the city just prior to the First World War; her father was employed as a blacksmith at Canadian General Electric. She was born in Winnipeg in 1921 and raised in California.

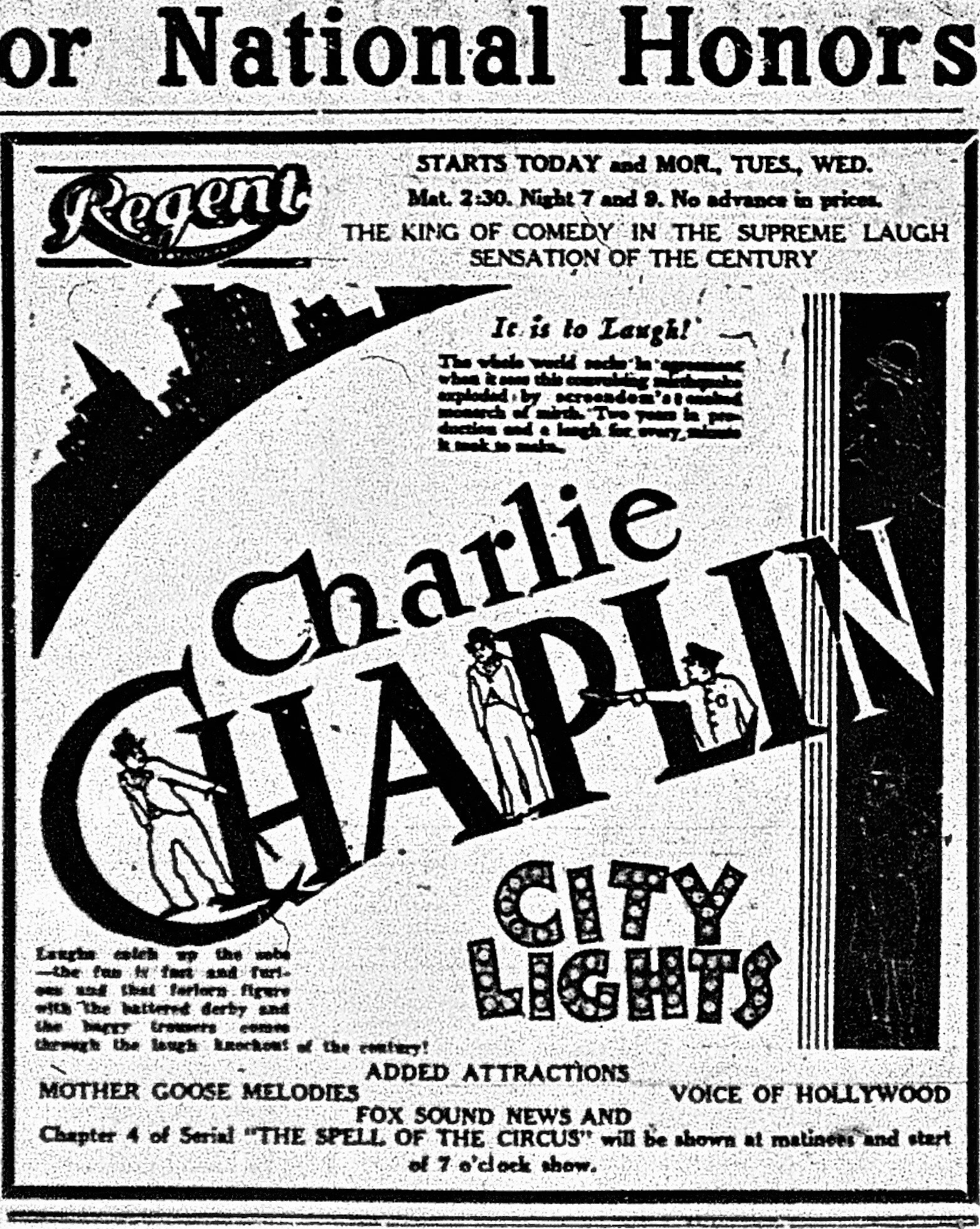

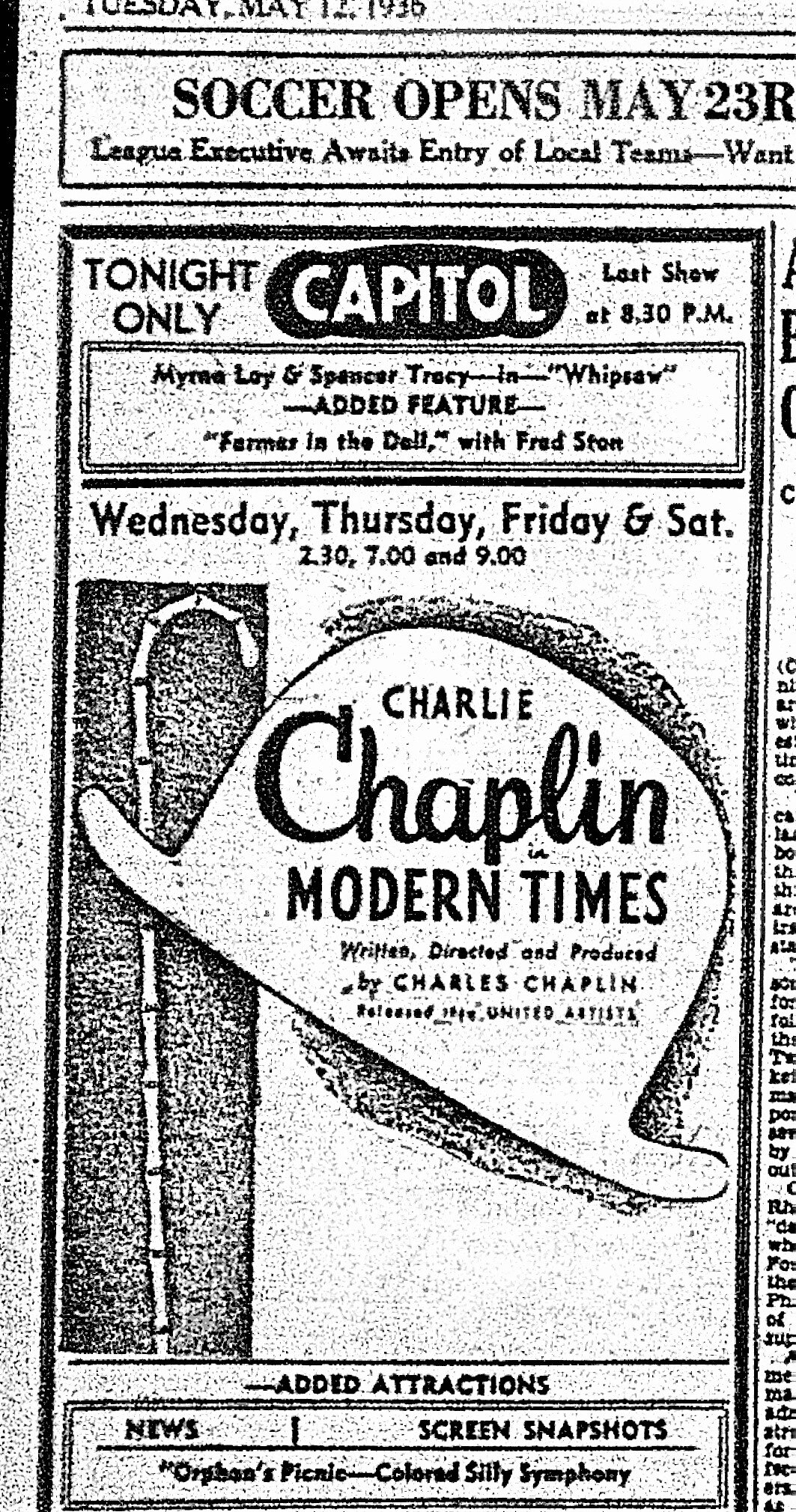

Left: Examiner, May 16, 1931, p.17. Right: Examiner, May 12, 1936, p.9. Chaplin remained “silent,” resisting the pressure to make a talking picture until The Great Dictator (1940); but still effective.

Double features and live on-stage attractions

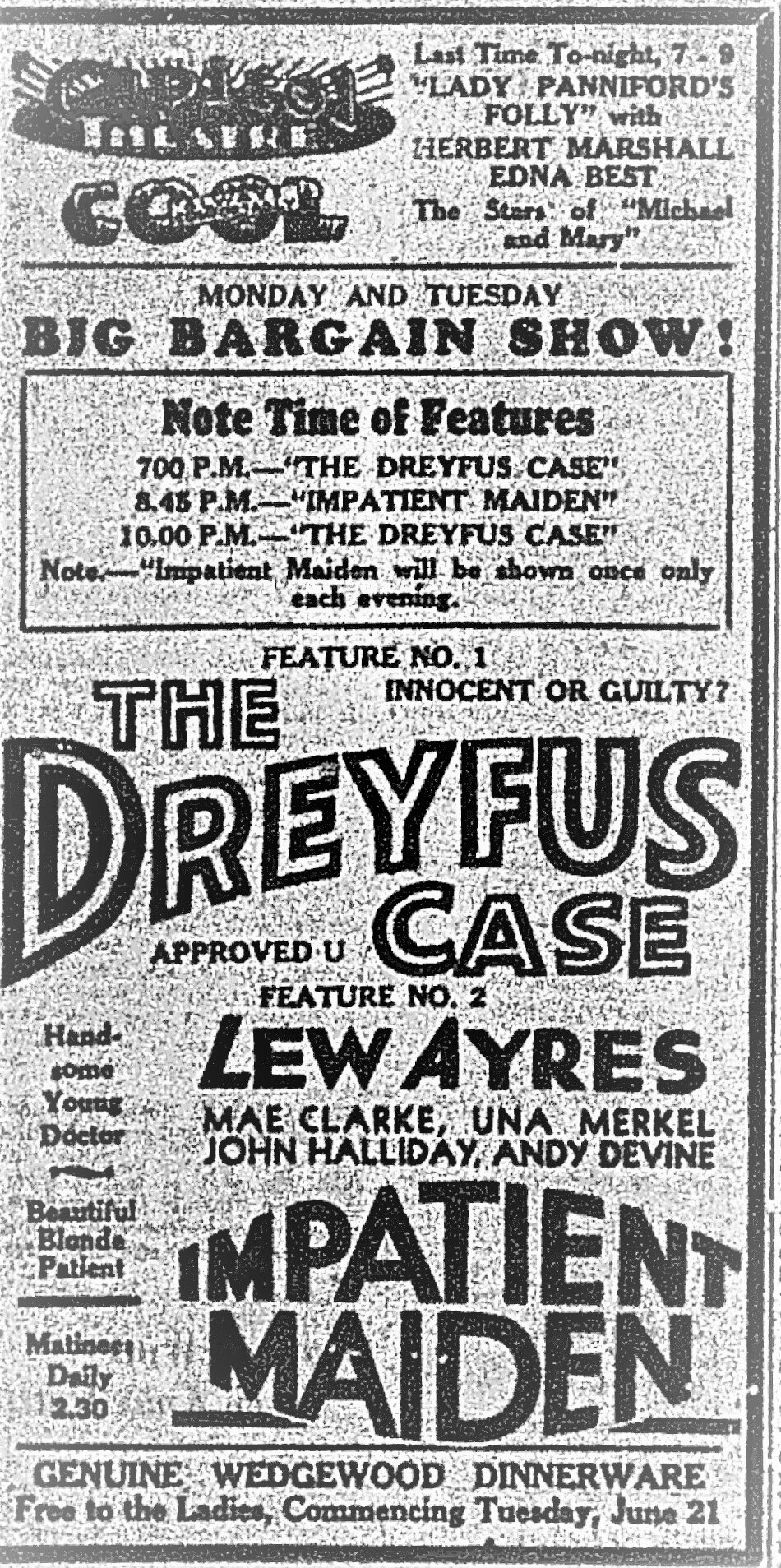

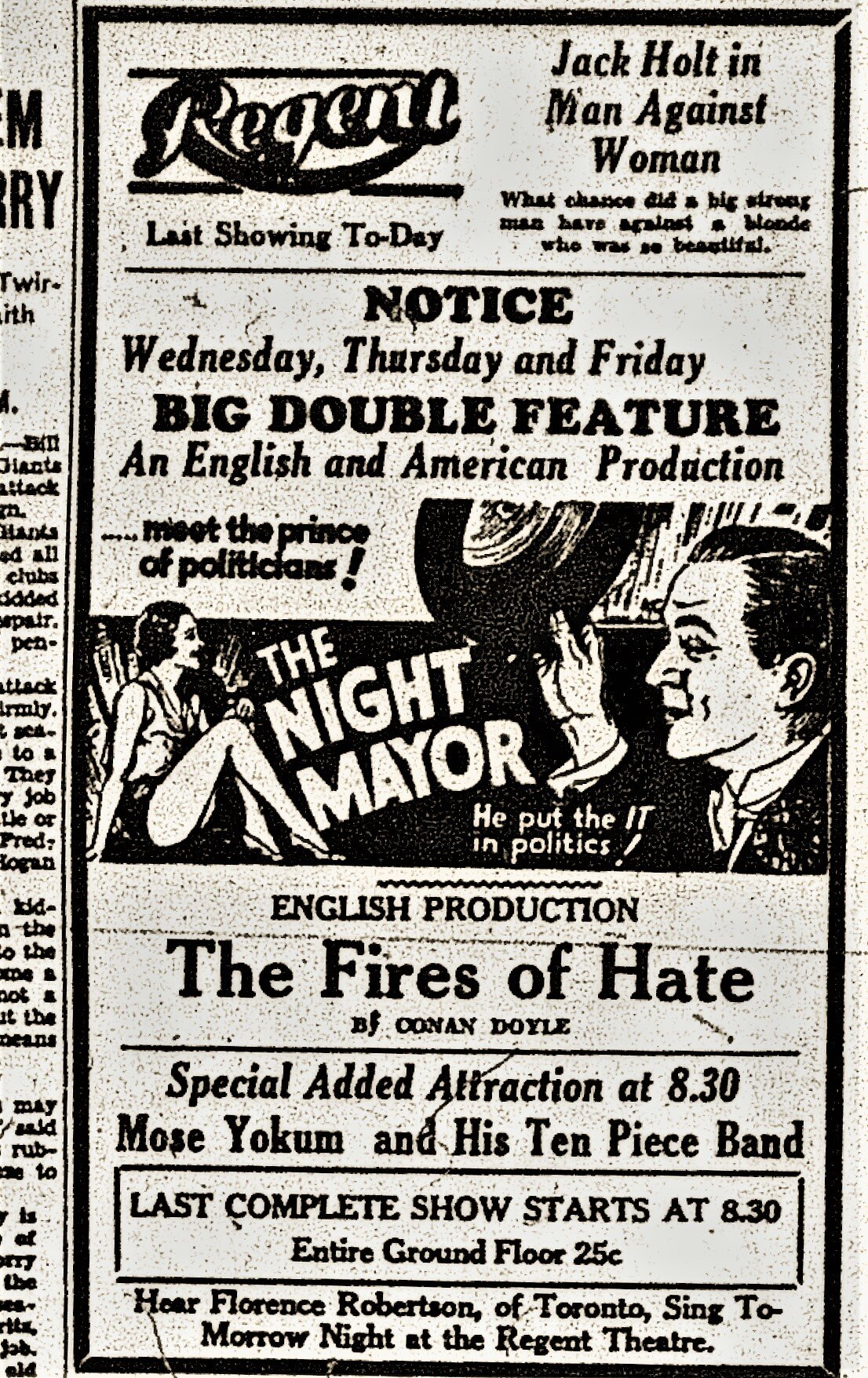

In the 1930s the theatres for the first time introduced double features — “Big Bargain Shows” (or two for the price of one) — and brought in live acts to appeal to the pocket book and help stem the Depression tide — and don’t forget the dinnerware!

Left: Examiner, June 11, 1932, p.9. Middle: Examiner, March 7, 1933, p.9. Right: Examiner, Sept. 13, 1934, p.17. At the Regent, with a U.S.-British double feature plus the added treat of the local Mose Yokum and his ten-piece band, the price went up a little.

Left: Examiner, April 7, 1931, p.13. Middle: Examiner, April 17, 1931, p.17. Right: Examiner, April 25, 1936, p.9.

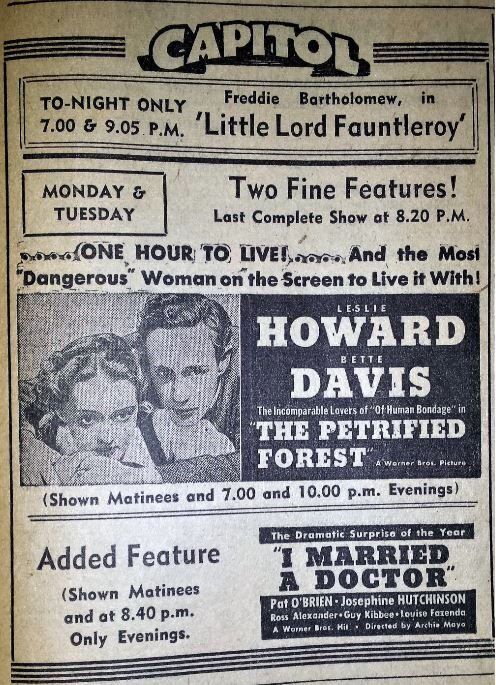

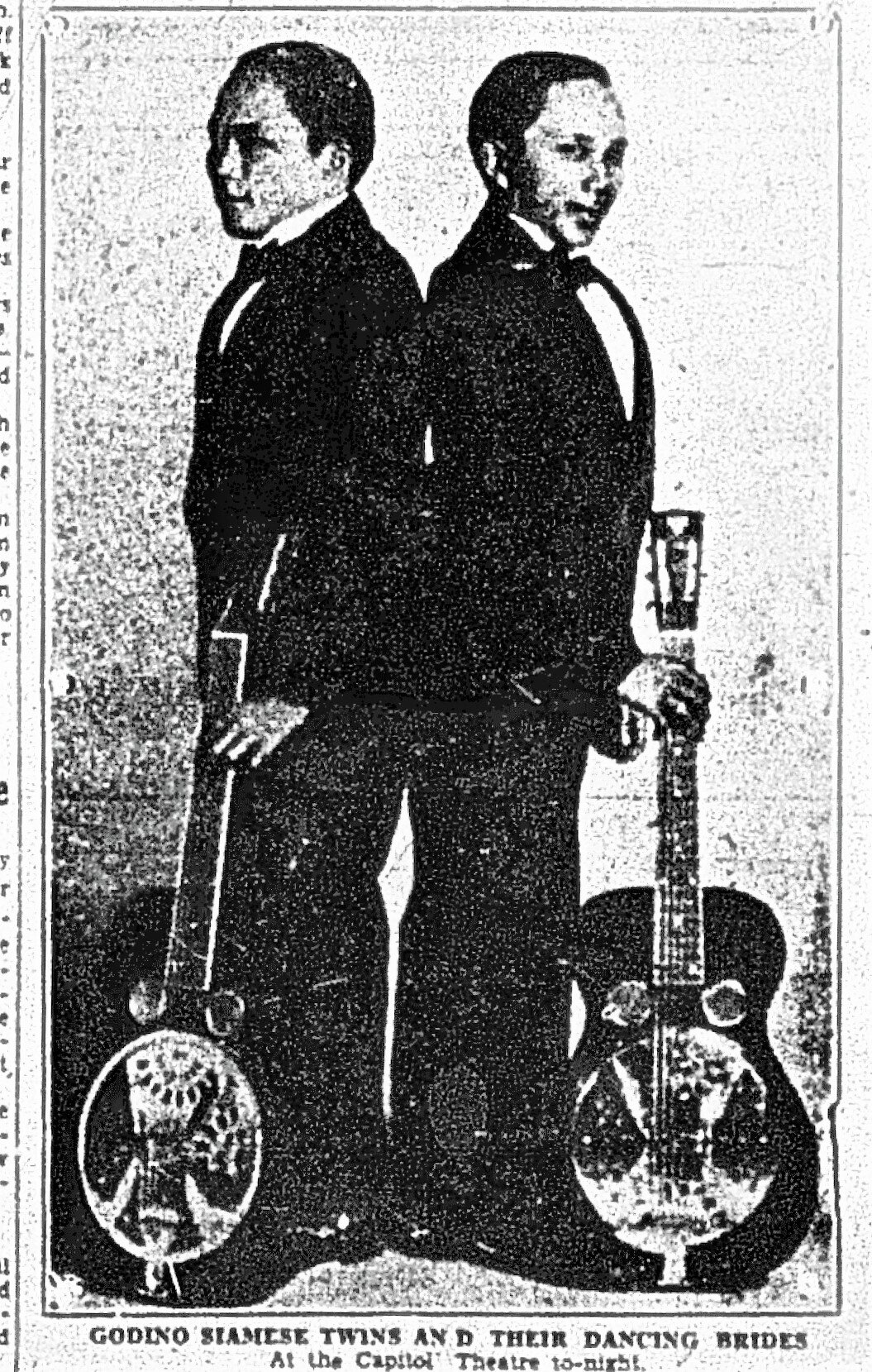

The days of live on-stage talent were far from gone: here, from the radio stars George Wade and His Corn Huskers to the popular (and dehumanizing) exotica of the Godino Twins — and their brides — “The only Male Siamese Twins in the Whole World — They Sing, Dance, Saxaphone Artists, Roller Skate and Perform the same feats as any normal young man can do.” And then, on the Capitol stage, an amateur vaudeville contest — before or after you watch the “Dangerous” Bette Davis.

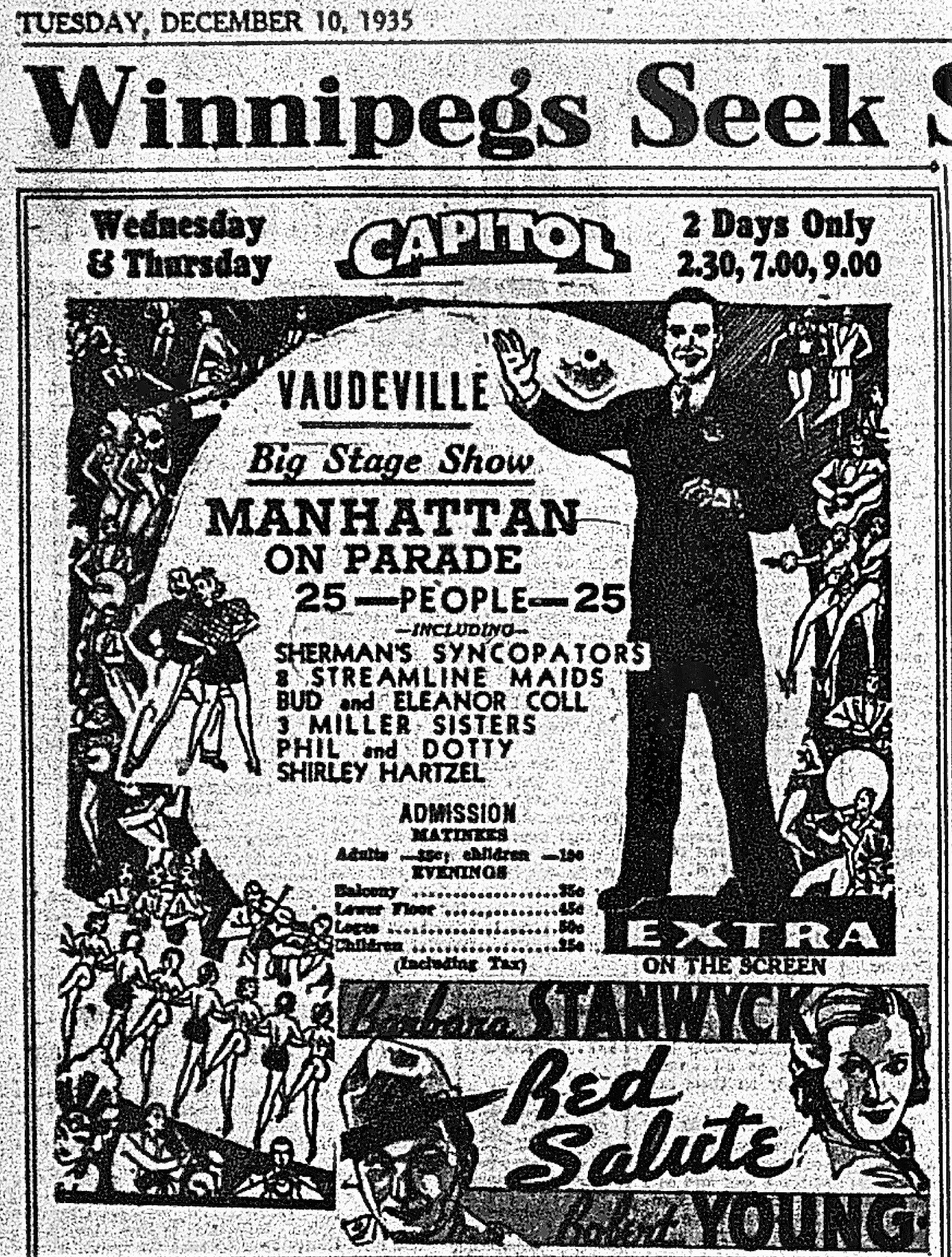

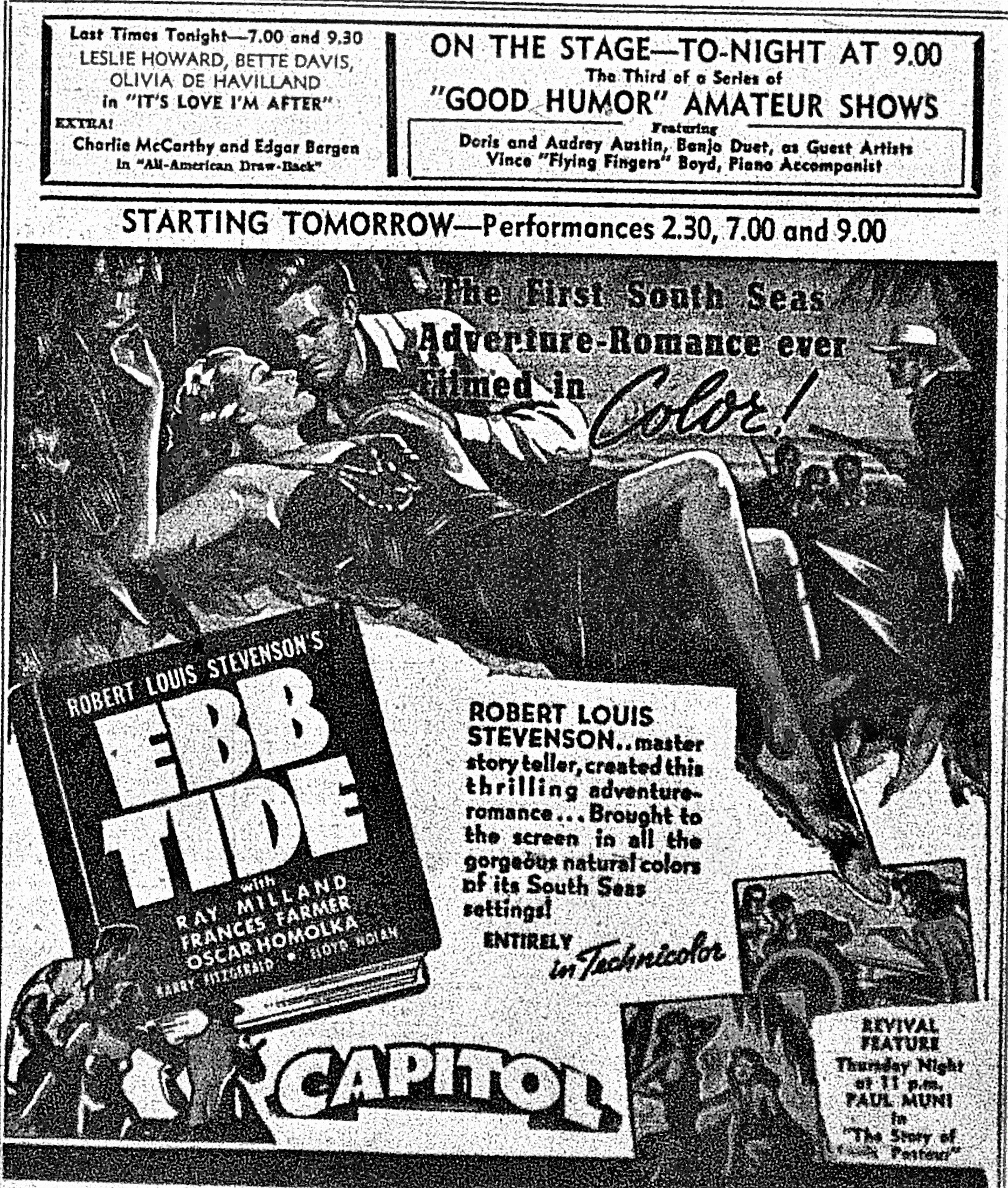

Left: Examiner, Dec. 10, 1935, p.7. Right: Examiner, Dec. 8, 1937, p.15.

“Big Stage” shows, whether brought in from elsewhere or local; and note, too, the “Revival Feature” coming soon — re-running older films became a standard late-night practice.

Left: Examiner, March 16, 1935, p.13. Right: Examiner, June 21, 1935, p.9.

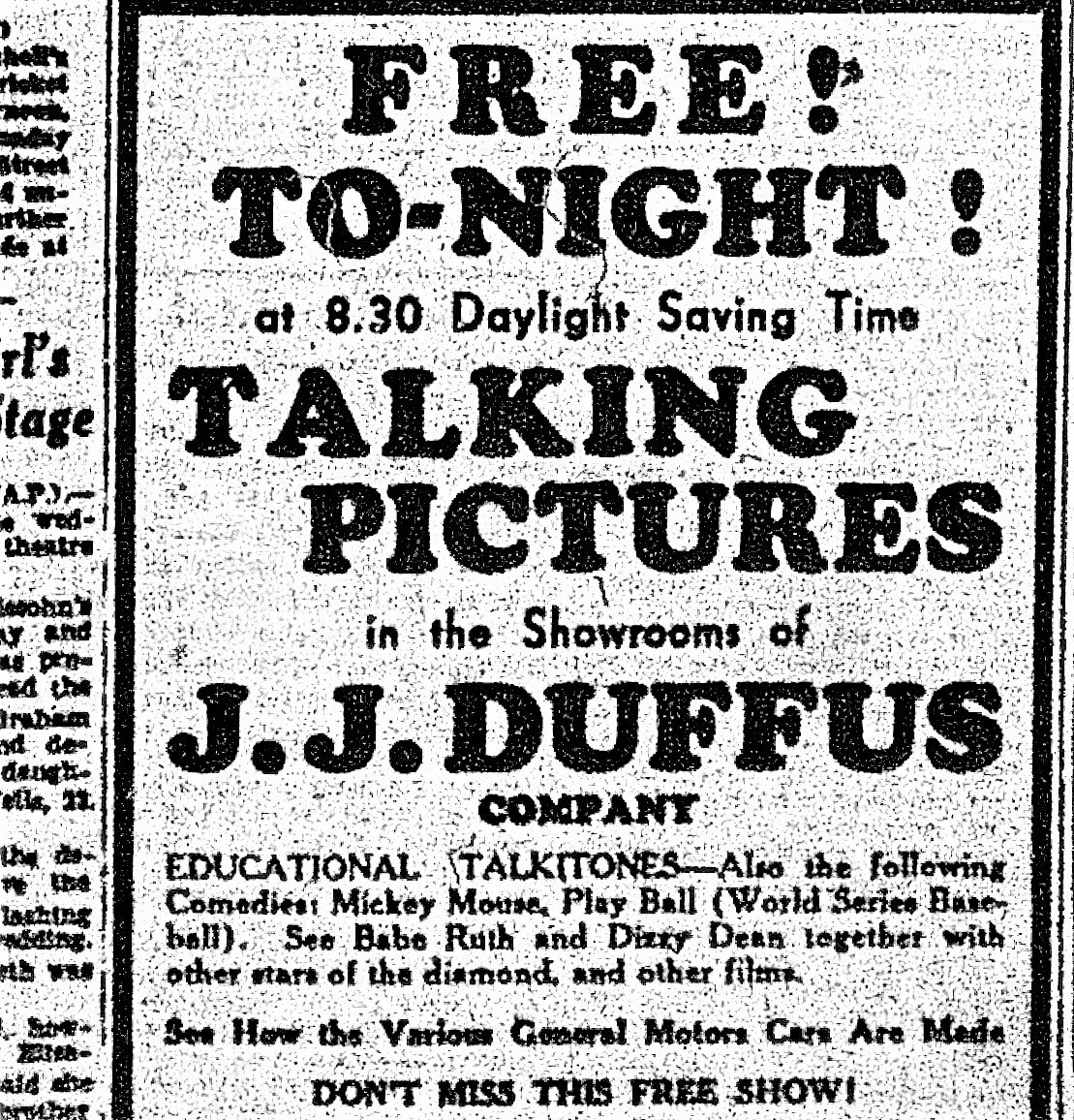

What became called newsreels had been screened at movie theatres since the 1910s. Most of us growing up in the late 1940s—early1950s, before television, took “The March of Time” newsreel for granted. Here, apparently, is the beginning. The Duffus ad is just a reminder that for most of their history, motion pictures could be seen in plenty of other places apart from theatres — here, in a downtown garage. “See Babe Ruth and Dizzy Dean” — and catch some of our General Motors products too.

SOME FULL-PAGE DISPLAYS . . .

Examiner, Oct. 30, 1937, p.11.

Examiner, Nov. 4, 1937, p.15. Full pages of “amusements,” here, unusually, with no sports.

Examiner, Jan. 11, 1938, p.11.

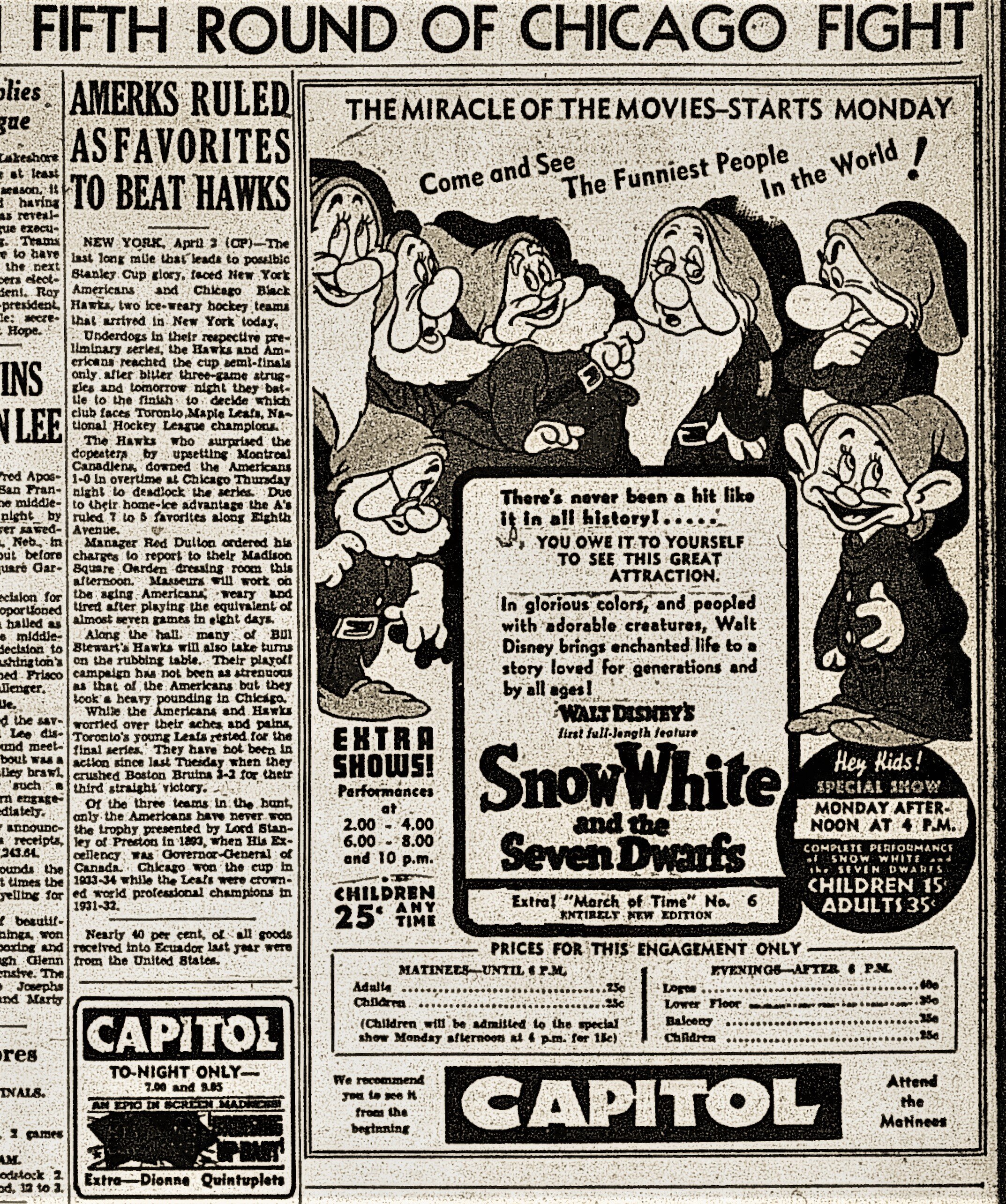

Towards the end of the decade, the arrival of Disney’s first animated feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

Left: Examiner, April 2, 1938, p.7. Middle: Examiner, April 4, 1938, p.14. Right: Examiner, April 7, 1938, p.7.

Snow White arrives to great fanfare — and the Capitol has another tie-in with Canadian Department Stores. It’s so popular it is held over. The first day, Monday, the theatre put on a special show for the kids at 4 p.m. One Peterborough man recalled years later how he had rushed downtown straight from school that day to see the picture. “Every child in town wanted to see it the first day it was shown.” Much to his dismay, when he got there he found that it was sold out.

Left: Examiner, March 3, 1938, p.15. At top left, Olympic skater Sonye Henye has begun her movie career, and a revival night has Bette Davis returning in Dangerous; at the Regent, Hopalong Cassidy — his “guns are out! To save a pal! To rescue a girl!” — and for some reason kids could get photo of his rival, Gene Autry

Middle: Examiner, March 30, 1938, p.7. Gene Autry is worried about menacing rangeland mobsters; while in the great Howard Hawks movie Bringing up Baby (1938), Cary Grant is troubled by a pet leopard. Also that most popular subject of the Depression years, the Dionne Quintuplets.

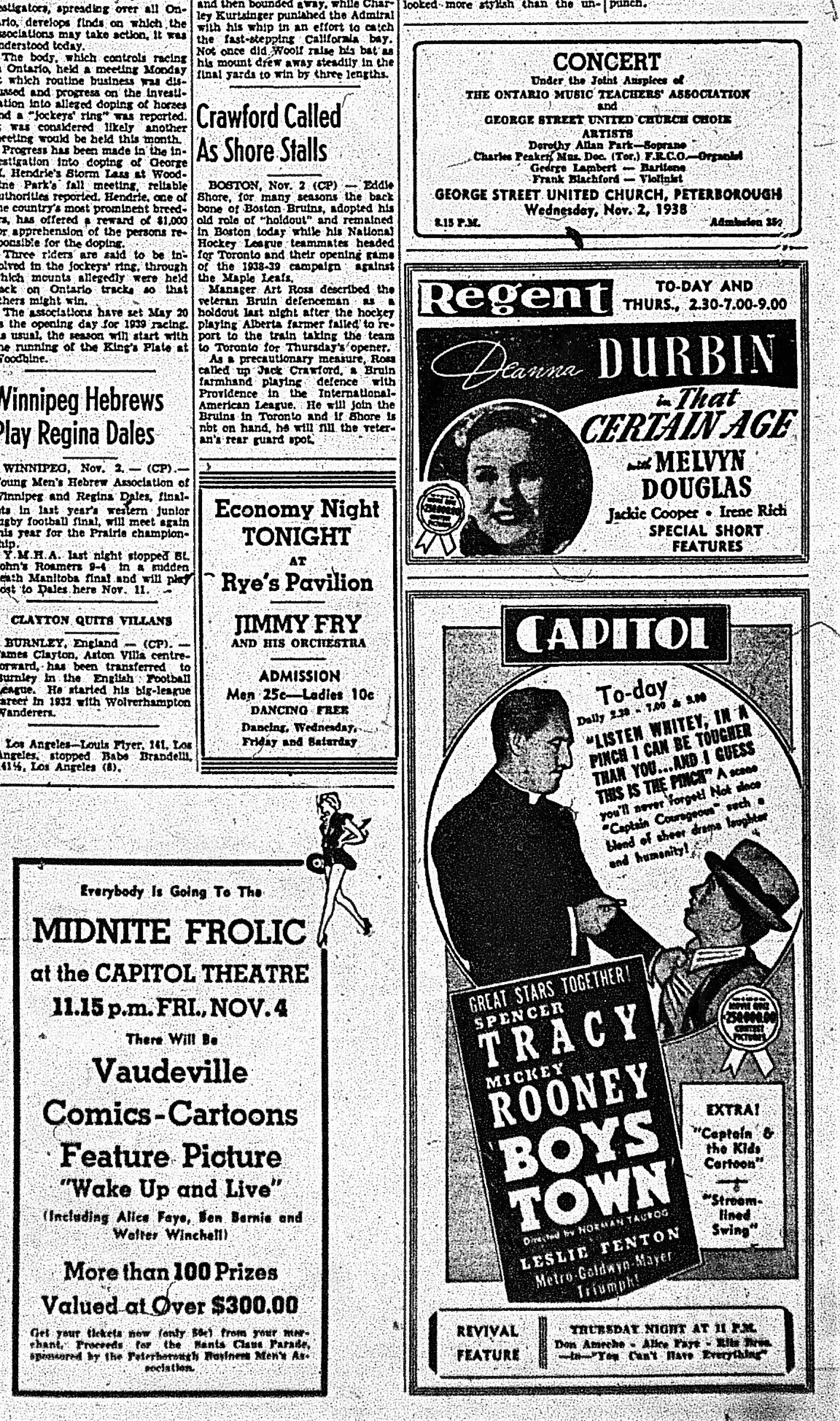

Right: Examiner, Nov. 2, 1938, p.9. Later that same year, Spencer Tracy and Mickey Rooney in Boys’ Town (1938), more Deanna Durbin, and a midnite frolic with vaudeville and prizes and all the rest. No wonder most everyone was going to the motion picture show.

The demise of the Grand Opera House

Meanwhile, in the beleaguered years of the Depression, that oldest (est. 1905), largest, most proud, and distinguished of the city’s venues, the Grand Opera House, uttered its last, largely unnoticed, gasps. It had opened its doors fewer and fewer times in the past decade, its vast space used mostly for local affairs. The days of giant travelling stage extravaganzas were long over. When “talkies” were arriving on the scene, the local owners considered the cost of rewiring its large space as prohibitive; they had already experienced concerns around the electrical expenses necessary just to keep the building open.

In the following years the introductory page of the directories for Peterborough, with its population of 23,000, continued to boast of the city’s array of “Amusements.” Even in 1928, although the Royal had finally been dropped from the theatre listings, the Directory’s opening page, as if pining for the old days, still touted the city’s bounty of an “Opera House, and three moving picture theatres.”

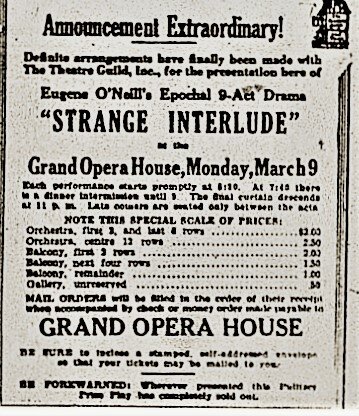

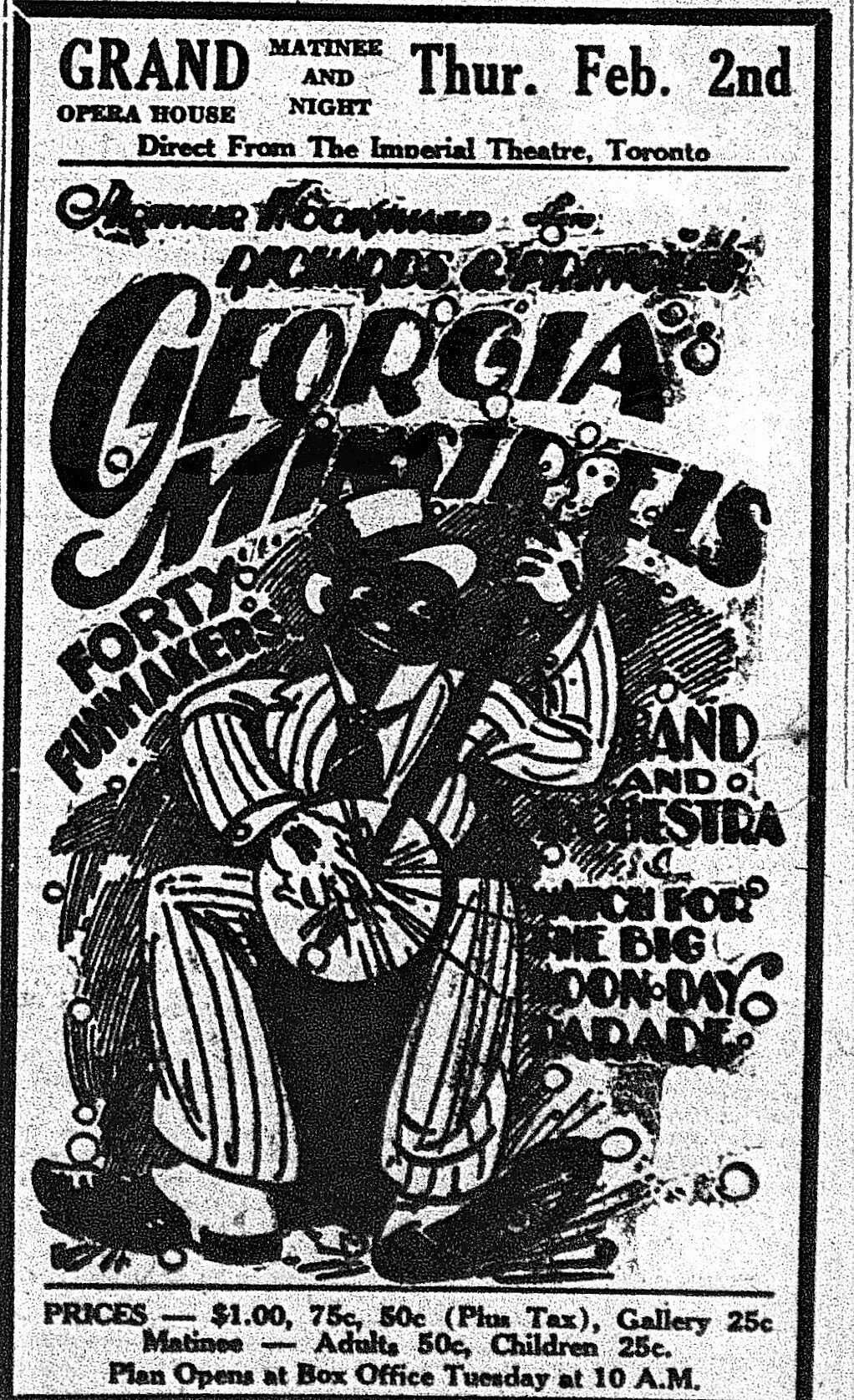

Left: Examiner, Feb. 25, 1931, p.13. Right: Examiner, Jan. 28, 1933, p.13.

The Eugene O’Neill play Strange Interlude (produced by the Theatre Guild of New York City) arrived in March 1931 for one night only. The Georgia Minstrels (“Direct from the Imperial Theatre, Toronto”) came on Feb. 2, 1933 — the last travelling attraction to make an appearance on the stage of the Grand. Other events held over the following years were purely local affairs presented by the likes of the Y.W.C.A., Women’s Patriotic League of Ashburnham, Kinsman Club, Dramatic Society of St. Alphonsus Lyceum, and the Choir and Men’s Association of St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church. A Home Maker’s School sponsored by the Examiner was successful in drawing huge crowds of women over several years (it was free and essentially about advertising goods, many of them made locally) — until its final run in May 1936; after that it moved to the Peterborough Collegiate Institute, and even later, for at least one time, to the new Centre Theatre.

Examiner, April 24, 1937, p.9. The Y.W.C.A. held its lavish pageants (complete with demonstrations of gymnastic exercises) annually from 1929 to 1937 at the Grand Opera House. This event marked the end of the Grand Opera House’s life as a performing centre.