1910s: War, Empire, and the Motion Picture Habit

Examiner, Aug. 12, 1911, np. Peterborough’s (dirt) main street and much to celebrate: a new company coming to town (the Bonner-Worth woolen mill), plus a new Canoe Company building — and motion pictures. Mike Pappas is now running both the Royal and the Princess — and will eventually take over what remains of the Crystal.

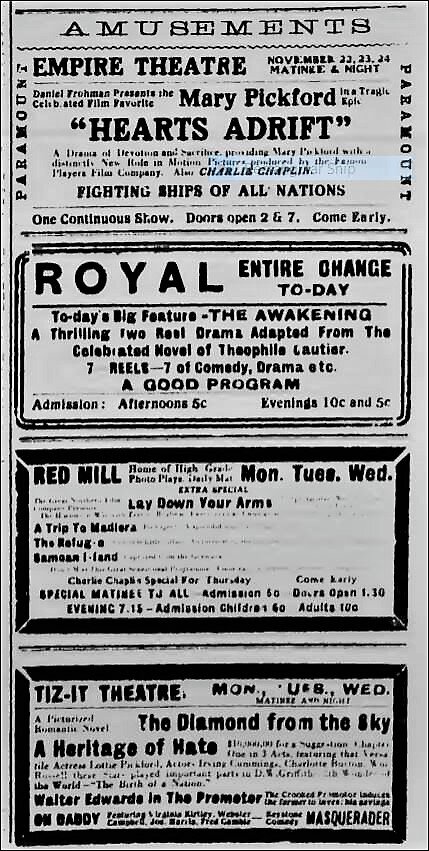

Huge ads, the arrival of a so-called Great War, an aptly named Empire Theatre, the rising stars of Pickford and Chaplin, and groundbreaking narrative spectacles: the short, hesitant steps of the motion picture from amusement to art form would follow, with a few stumbles along the way. The very names of the theatres — Royal, Princess, Empire — evoke solidarity with the British connection and lend legitimacy to the enterprises.

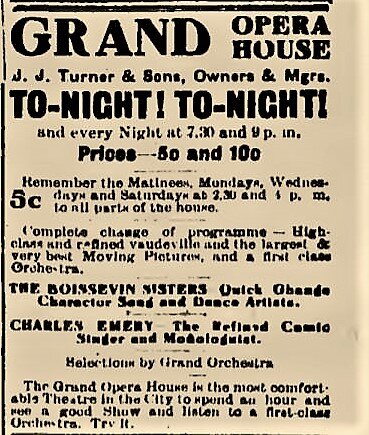

The Grand Opera House — and its motion pictures

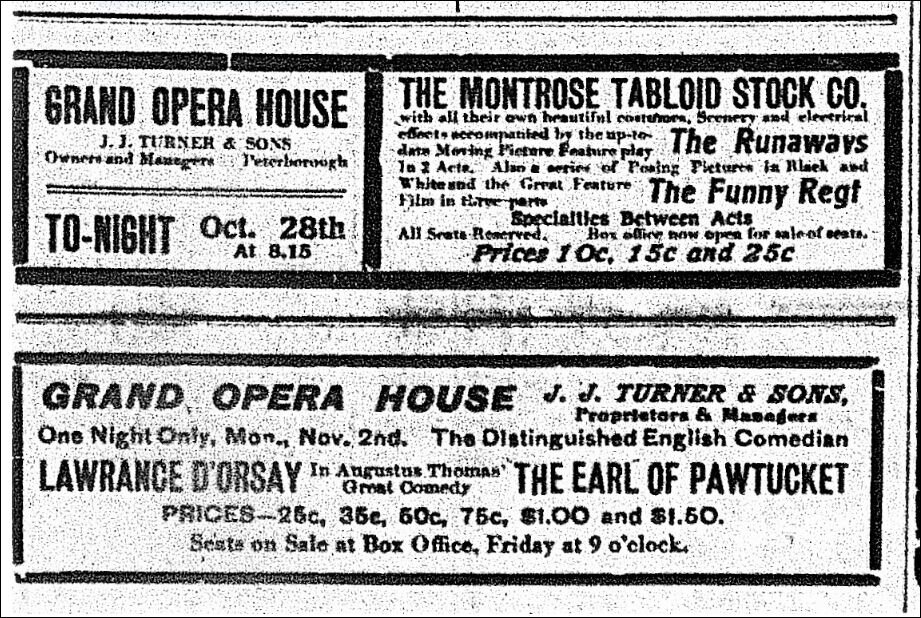

Examiner, Nov. 3, 1910, p.4. Despite the British connection, there was also “America” to the south — and no border so far as commercial entertainment went. Above is one among the many lavish live (U.S.) attractions at the Grand Opera House — but this largest (by far) theatre in town also gradually screened more and more motion pictures, until it could promise “No More Dark Nights.” That is, when it didn’t have live attractions, it would keep its doors open by screening moving films. By 1913—14, in large theatres emphasizing travelling stage extravaganzas, dark nights had become more numerous, and, as one report put it, “at last it dawned upon the theatrical interests that waiting for the wane of the moving picture was a cheerless and unproductive occupation.”

Examiner, Jan. 24, 1914. “No more dark night” — with a new curtain, too.

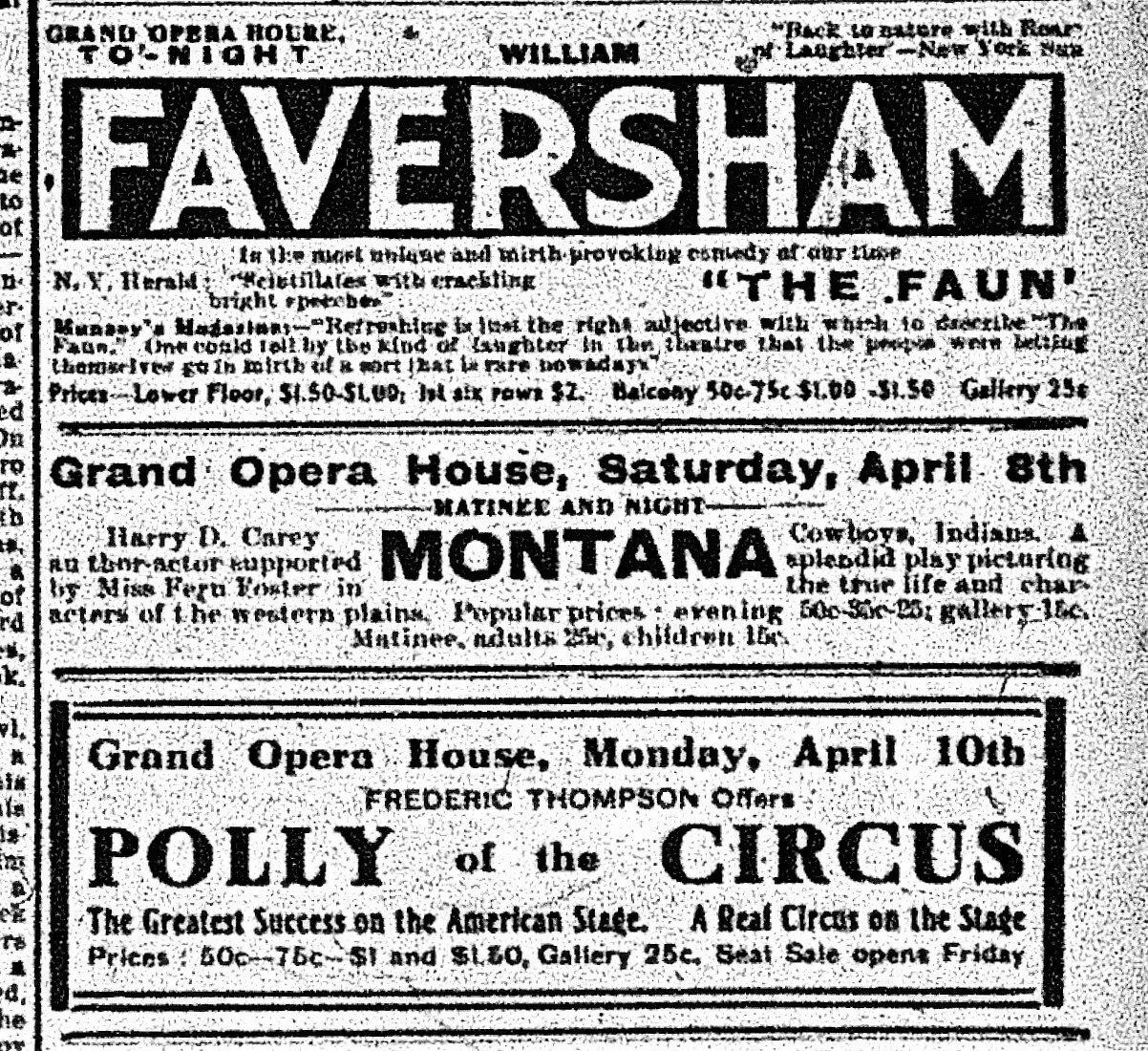

Left: Examiner, Sept. 7, 1910. Right: Examiner, April 5, 1911. The Grand, even earlier, supplemented its live attractions with evenings and afternoons of motion pictures. Harry Carey’s appearance in the stage show Montana marked his second time in town in less than a year; he went on to be one of the biggest Western stars in the early period of moving pictures. William Faversham, who appeared in a dozen or so Hollywood films after 1915, was one of the greats of the British stage; his picture was on a wall in the home of Rupert Davies, the father of novelist and Peterborough newspaper editor Robertson Davies. His movie The Sin That Was His (1920) screened in Peterborough in November 1921, and he appeared on the Grand’s stage once again, with my own American cousin, Sarah Truax, in 1925.

Royal & Princess & Crystal/Red Mill & Grand Opera House

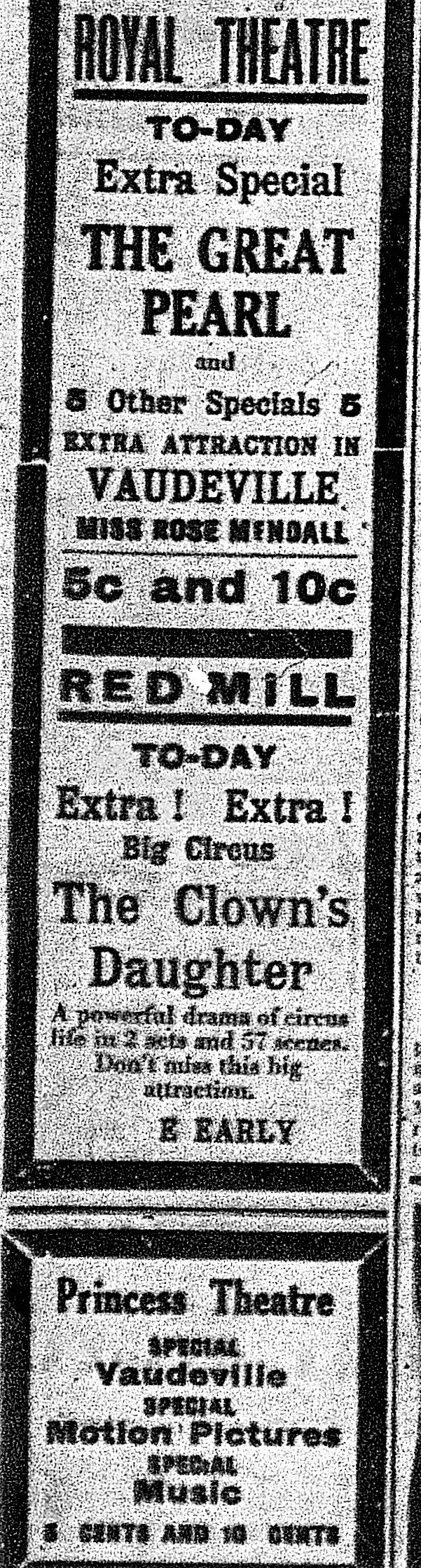

Examiner, Jan. 7, 1911, p.1. The Royal mixed its motion pictures with live vaudeville acts. A lecturer was often on hand at early silent films to stand up front and explain what was happening on screen, as in this Western program, “lectured by a Cheyenne Cowboy,” at the Princess.

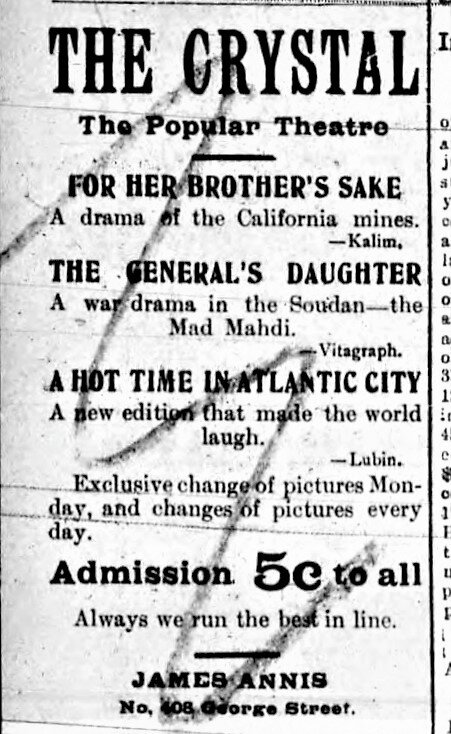

Left: The Crystal Theatre’s last ad, Daily Evening Review, Jan. 16, 1912, p.5. On Jan. 7 a notice had appeared indicating that the theatre was up for sale — and it was soon replaced by the Red Mill, owned and managed by city newcomer Herbert Clayton, a self-described “theatre man” who had a motion picture background in Toronto and Hamilton.

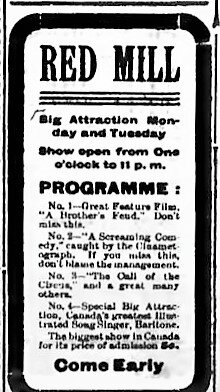

Middle: Examiner, Feb. 17, 1912, p.16. The Red Mill, replacing the Crystal, opened on Feb. 16, 1912.

Right: Examiner, Dec. 9, 1913, p.1. The three George Street theatres: Royal, Red Mill, and Princess. The Royal and Princess both had vaudeville along with the short pictures. The Red Mill’s film in “2 acts” means that it was showing a longer film than usual, of two reels (with 57 scenes!).

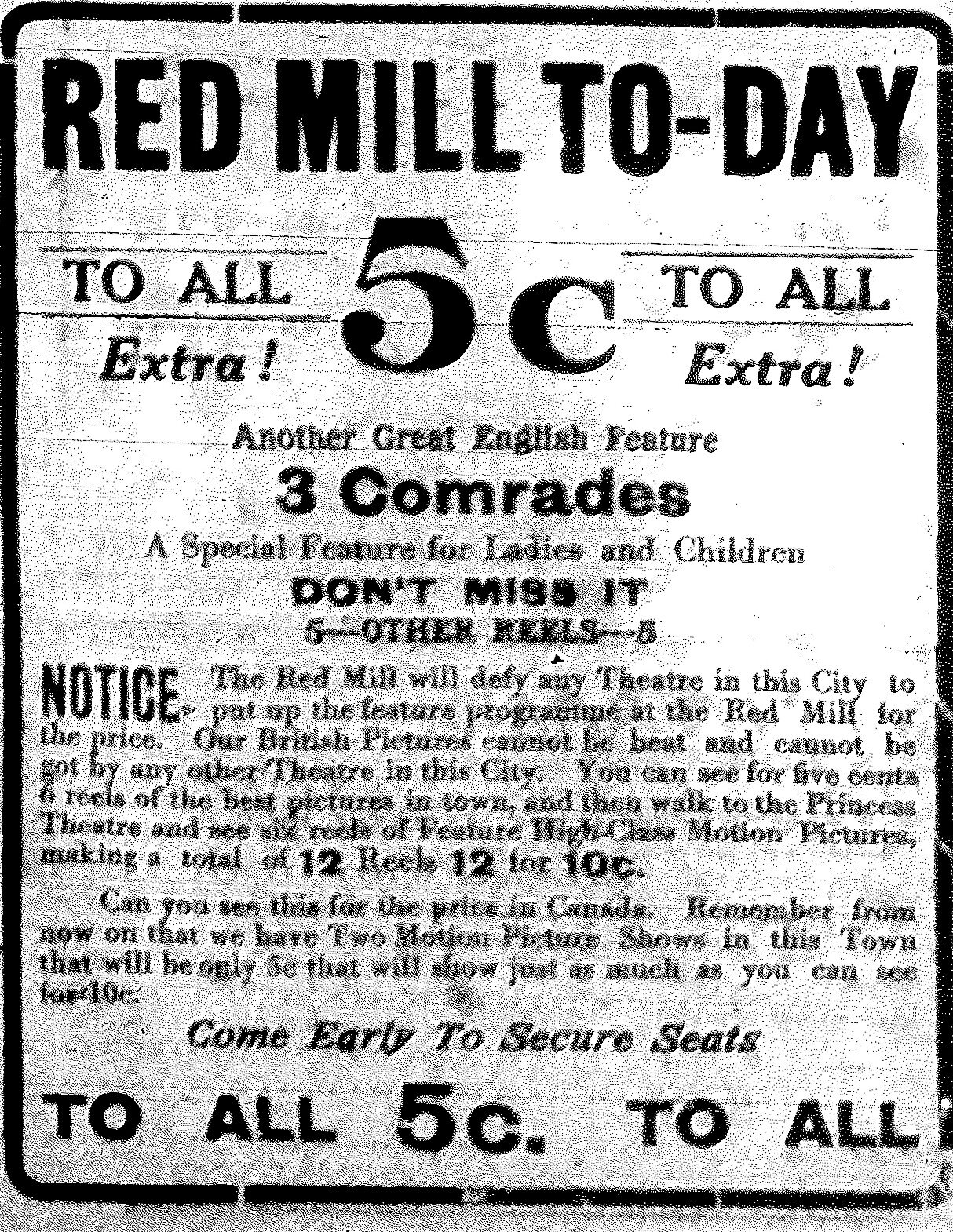

Above: Examiner, Jan. 27, 1914, p.1. An extraordinary ad (on the part of manager Herbert Clayton), both “defying” other theatres to match the program at the Red Mill and encouraging motion picture lovers to see the pictures there and then walk across the street to see even more — for the same cheap price of five cents — at the Princess. Although the ad makes much of “British pictures,” the film 3 Comrades is not on any British list I’ve found; it might have been from Denmark (a film of that name was released in May 1913).

Meanwhile, below, the Grand Opera House had the “big” pictures, along with its usual live entertainment.

Examiner, Jan. 16, 1912, p.5. “Direct from two weeks in Massey Hall.”

Examiner, March 18, 1914, p.10. An Italian film — a “feature,” of 8 reels. With the coming of war, the films from abroad would dry up and U.S. productions would take over.

The predominantly short one- or two-reel silent motion pictures were now being joined by longer “features.” “You may have seen the play, now come and see the Pictures.” The Red Mill’s Herbert Clayton was a masterful promoter of his theatre — and he was soon also managing the Princess and the Royal, establishing a small empire before getting into financial difficulties and going off to war in summer 1915.

Introducing a fifth theatre — the Empire — and the Princess becomes the Tiz-It

Friday, July 24, 1914: just a few days before the beginning of the Great War (1914—18), a local veterinarian, Fred Robinson, established a new theatre, the Empire, on the premises of his otherwise horse-abundant livery-stable and taxi business on Charlotte Street (north side just east of Alymer). Peterborough now had five theatres: Red Mill, Royal, Princess, Empire, and Grand Opera House, which that same day was screening “the Bible in motion pictures.” The city had grown to over 25,000.

Examiner, July 27, 1914, p.12. These small notices appeared daily for the next month or so in lieu of the usual theatre advertisements.

Examiner, Oct. 28, 1914, p.13. The Empire features the first installment of The Adventures of Kathlyn (1913, and not “Kathleen”) — introducing a new filmic phenomenon, the serial, a multi-episode story shown in parts over a period of time — famed for introducing the “cliff-hanger” ending. In early January 1915, the series was transferred to the Royal, which had the “added advantage of two machines and two operators” so that “picture lovers will be able to see this interesting photo play without any interruptions.”

Examiner, Sept. 11, 1914, p.13. This is the first actual Empire ad I spotted. Apologies for the quality. At least we know it was offering “the motion picture sensation of the year.”

Examiner, Feb. 24,1915, p.11. After a small fire in December, just before Christmas, the Princess closed for a while; it then reopened at the same location (after a naming contest) as the Tiz-It on Feb. 20, 1915. Its manager, Herbert Clayton, would depart that year after joining the army.

Five theatres — plenty of moving pictures, of all shapes and sizes

Examiner, Oct. 28, 1914, p.13. When a travelling comedy act, the Montrose Tabloid Stock Co., came to the Grand Opera house, it featured “Specialities Between Acts” and moving pictures.

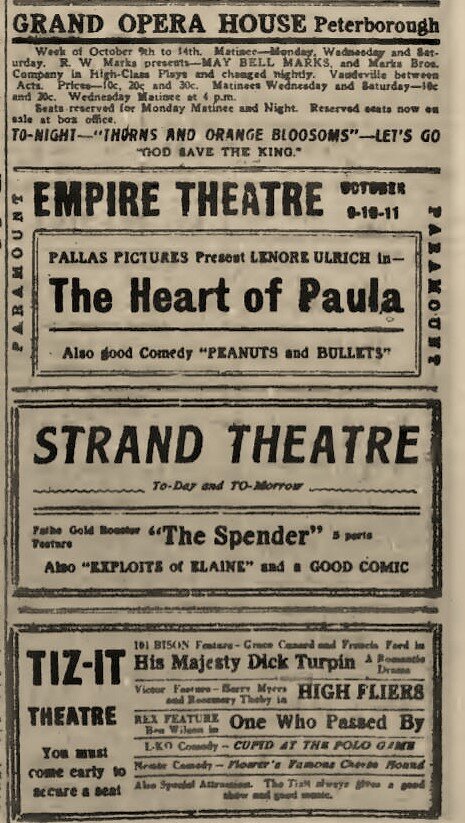

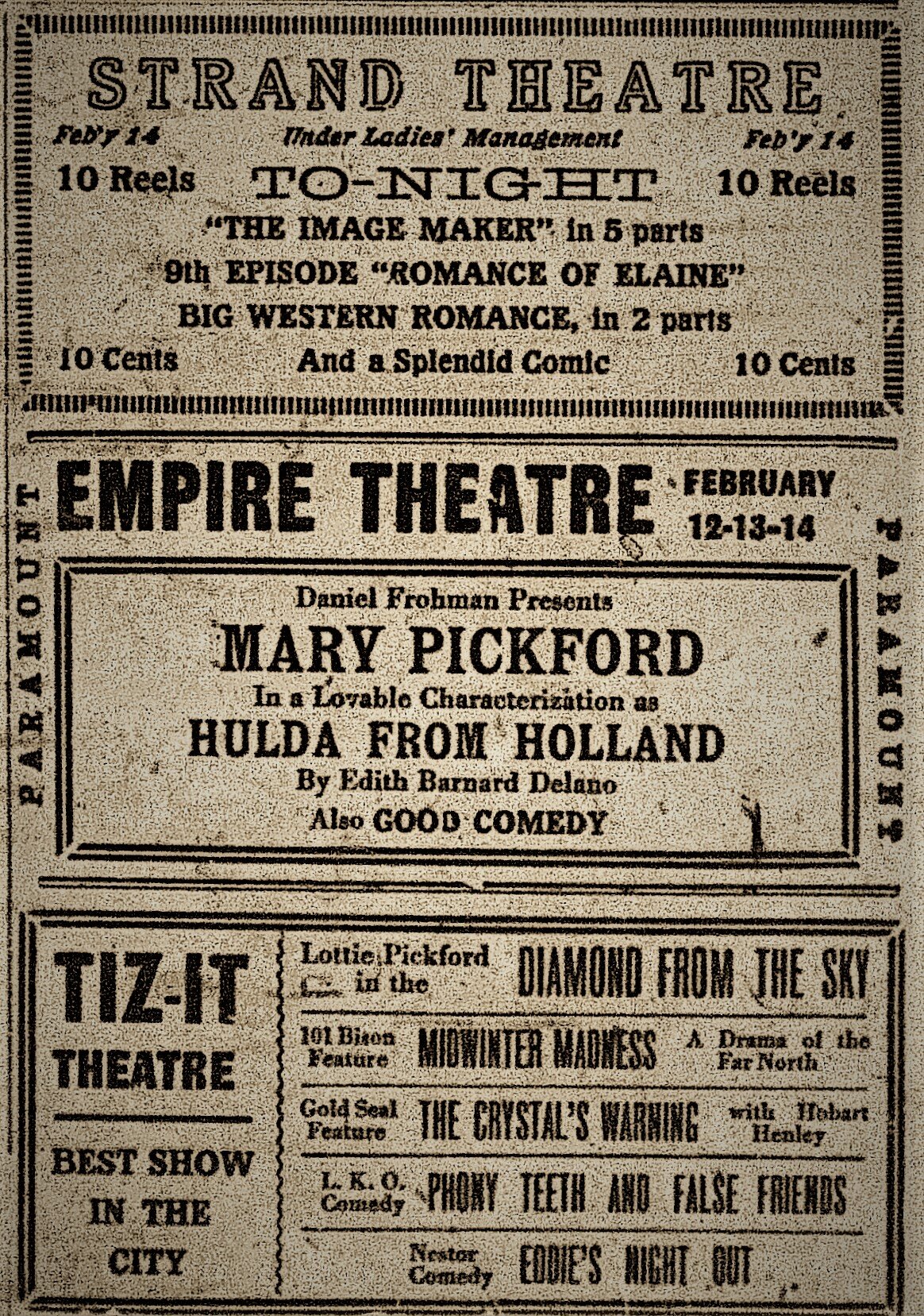

Left: Examiner, Nov. 24,1915, p.9. Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin, among others, at four downtown theatres.

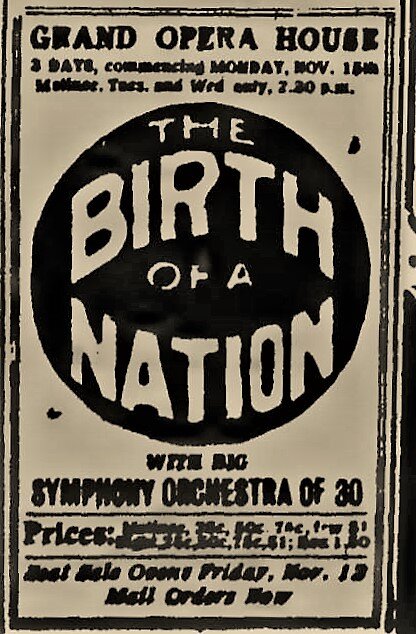

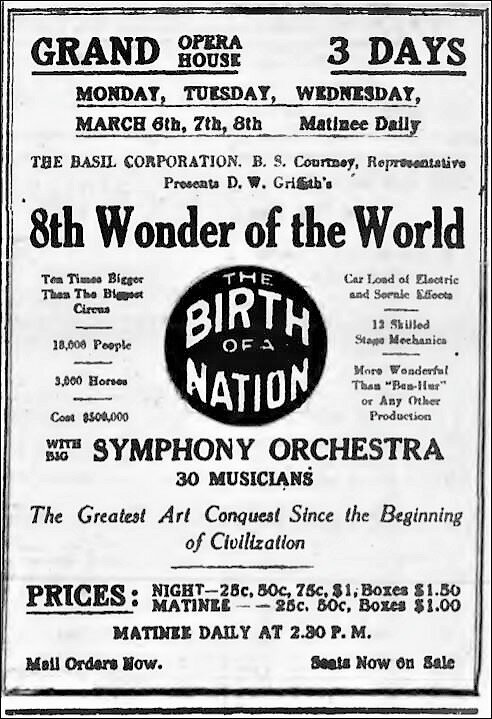

Middle: Examiner, Nov. 11, 1915, p.11. Around the same time, at the Grand Opera House, the ground-breaking (cinematically) and notoriously racist (politically and culturally) The Birth of a Nation (1915), directed by D.W. Griffith.

Right: Examiner, March 4, 1916, p.11. Birth of a Nation returns the following spring. It is worth pausing to consider the popularity of this film: it came back to the majority white town again and again over the following years — and even turned up once again as late as June 1956 at the Centre Theatre.

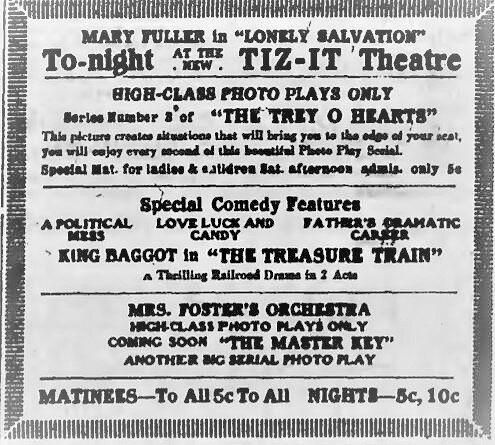

Left: Examiner, March 20, 1915, p.13, with Mrs. Foster’s Orchestra; Mrs. Foster (and that was how her name usually appeared in the newspaper) was Eveline M. Foster, who lived with her husband, John, for years at 585 Patterson St. She played violin and piano at the silent motion picture theatres and was also a prominent member of the Grand Opera House orchestra. Legend has it that she played in every symphony concert that took place in Peterborough. After the talkies came in and her gigs decreased, she gave music lessons to children for decades and made music as well at Knox United Church. She died in 1968.

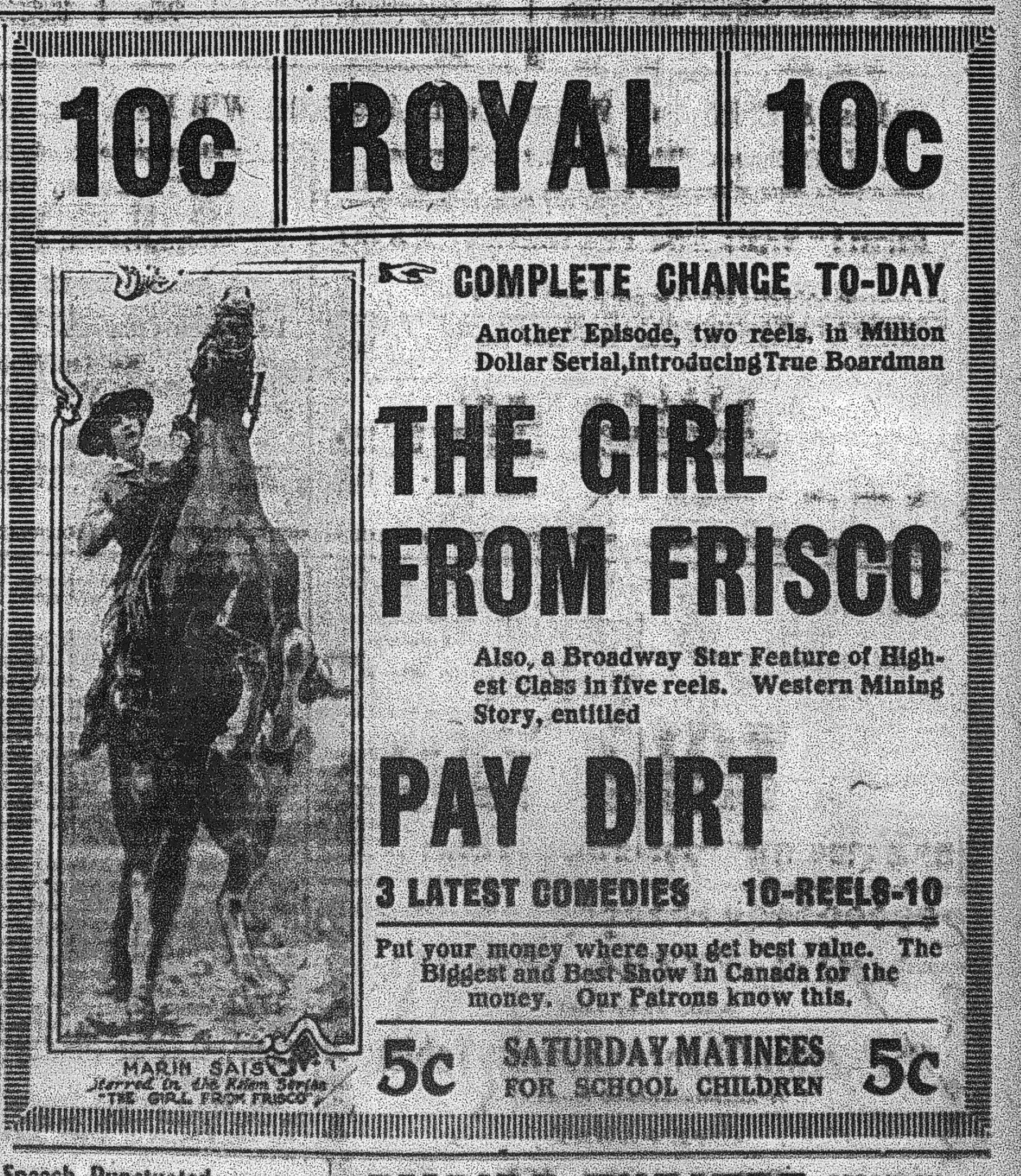

Right, above: Examiner, Feb. 9, 1917, p.11. The Royal gives top billing not to its “feature” but to The Girl from Frisco (1916) — a 25-episode serial that began playing weekly at the Royal on Friday, Nov. 10, 1916 and lasted well into spring 1917.

Examiner, Dec. 11, 1914, p.8. The Empire luring boys and girls through the “Wanted” column.

A good many of the serials of the 1910s featured women as feisty main characters. The length of the program is now 10 reels. An operator could crank a silent film at whatever speed seemed to suit the need or mood; a silent film reel might have been somewhere between 12 and 15 minutes, perhaps a little more.

The length of the program had increased from the early days; perhaps now an hour and a half, or more, depending on music and breaks. Still only a dime for evenings — and a nickel for afternoons and children’s matinees. The pull of Saturday matinees for children began in the 1910s and continued for decades to come.

Examiner, April 15, 1916, p.17. The Royal asserts its supremacy — and its union operators (or projectionists).

Vernon’s City of Peterborough Directory, 1916, p.809.

Examiner, May 29, 1916, p.11.

From the Crystal to the Red Mill and now the Strand — and the Tiz-It closes its doors

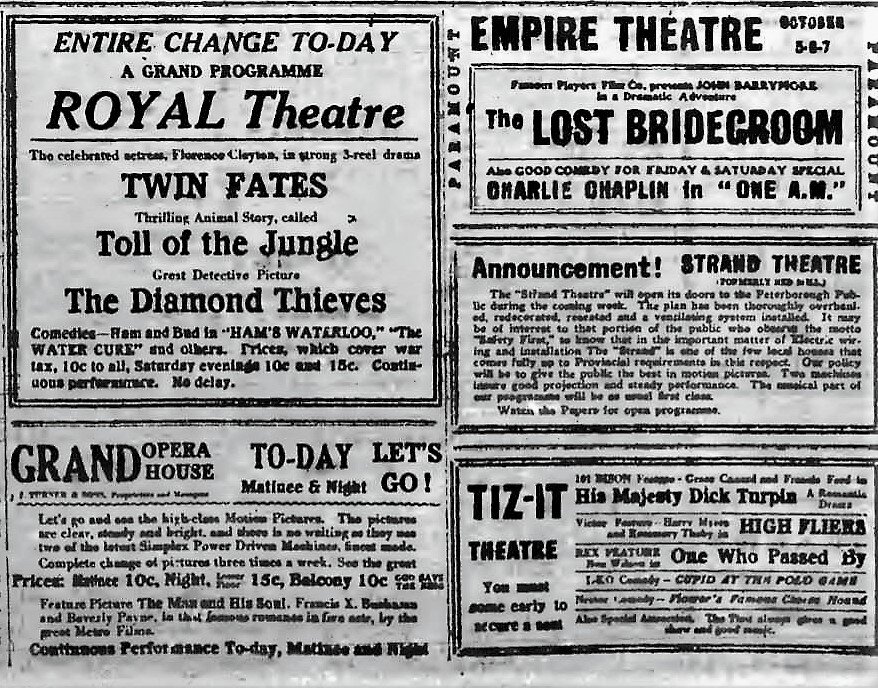

Left two columns: Examiner, Oct. 6,1916, p.13. Right: Examiner, Oct. 10, 1916, p.11. A downtown thick with motion picture theatres. “Let’s go and see the high-class Motion Pictures.” With two projectors, there is now no waiting for reel changes.

On Oct. 7, 1916, the Red Mill morphed into the Strand Theatre under the ownership of the Schneider brothers, long-time Peterborough jewellers. At some point the Schneiders combined with Charles Rishor, a wholesale grocer and businessman (Rishor Ltd.) in joint ownership, forming Schneider-Rishor Ltd. (The Schneiders and Rishors lived next door to each other on London Street.)

Left: Examiner, Feb. 14,1917, p.7. Although its ownership was male, the Strand was now “under ladies management” — and it also had “Lady Ushers.” Perhaps that was because of the war conditions, but women at the time were playing a more prominent part in the motion picture industry as compared to later on. (See “Women in Silent Film Days: Politics and an Evening’s Entertainment at the Empire Theatre.”) Perhaps the theatre was further reminding those regular patrons of the afternoon and early evenings that they would feel safe and secure within its small confines.

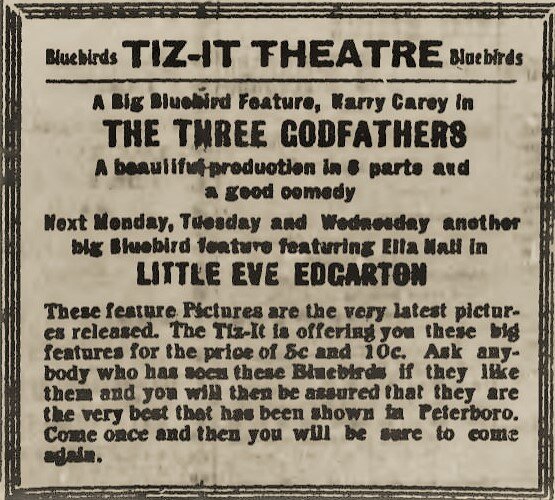

Right: Examiner, May 26, 1917, p.19. The Tiz-It’s movie that Saturday featured Harry Carey, who had appeared in person on the stage of the Grand Opera House some years earlier — and despite the promise of a new film policy for “next Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday,” this was the last ad seen for the Tiz-It, which closed without fanfare in the following days. Despite the ad, patrons were not at all able “to come again.” Afterwards the site, which had housed the Princess and then the Tiz-It over a period of ten years, became home to a succession of long-lasting restaurants: the Paris Cafe and, as of the 1950s, the Hi Tops Restaurant, and in the 2010s, Real Thai Cuisine.

*****

Through the decade the Grand Opera House played so many movies that when it came to live attractions, over and over again it had to make sure the newspaper readers knew that the event was “a real play” or a live comedy/drama and “not a moving picture.”

Examiner, Oct. 23, 1915, p.13.

Examiner, Nov. 21, 1917, p.11.

Examiner, Jan. 16, 1918, p.11.

Examiner, Aug. 30, 1919, p.9. Amidst so many motion pictures — with the most popular stars of the day — playing at the Grand Opera House, the ad for the play “7 Days’ Leave” has to repeat the message “Not a moving picture” twice.

Examiner, March 7, 1918, p7. “New Bill at the Grand”: After a horrific fire in January 1918 ravished the buildings on the east side of George Street just north of the Market Hall, for a short while, until the theatre was rebuilt, the Royal showed its films at the Grand Opera House. A newly renovated Royal Theatre reopened its doors around Christmas Day, 1918.

The Royal becomes the Allen — welcoming a Canadian movie exhibition chain

On Sept. 1, 1919, the Allen Theatre, owned by Allen Theatre Enterprises, Canada’s original national motion picture chain (based in Toronto), opened at 348 George St., replacing the Royal for a short period. Said an Examiner report: “citizens will scarcely be able to recognize the theatre.”

Left: Examiner, Aug. 30,1919, p.9. Right: Examiner, Sept. 2, p.6. At the Allen [not Allan], on screen, the famous Western star William S. Hart and the soon to be notorious Fatty Arbuckle.

Examiner, Sept. 8, 1919, p.11.

Examiner, Dec. 9, 1919, p.11.

In 1919, after the end of the war, then, Peterborough’s downtown was a lively place, with four theatres showing motion pictures: the Grand Opera House, Royal/Allen, Strand, and Empire — not to mention boxing and wrestling at the Brock St. Rink and much more. By the 1930s all of those four houses had vanished like abandoned love interests in countless romantic movies.