Women in Silent Film Days: Politics and An Evening’s Entertainment at the Empire Theatre

Peterborough Examiner, March 19, 1920, p.9.

Politics, Women, and Experimental Marriage . . .

Gender matters! Melodrama and marriage! And a Canadian scenic!

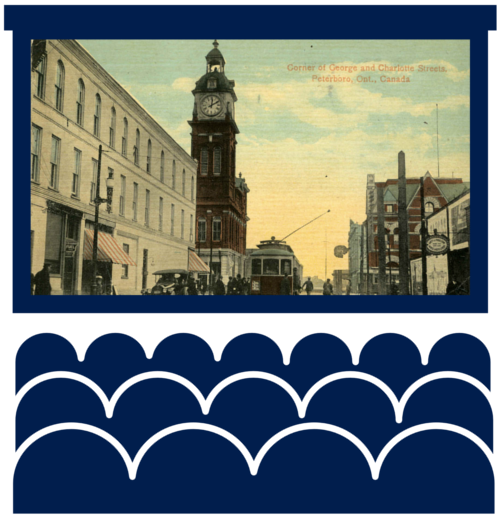

Over three days in spring 1920 the Empire Theatre on Charlotte Street offered all that and more.

The theatre was screening two big five-reelers (about 150 minutes in all, depending on how quickly the projectionist was turning the crank), plus a ten-minute scenic short.

Empire Theatre. C.R. Banks, in Overland car with children, 226 Charlotte St., early 1920s. Courtesy Trent Valley Archives.

Although the ad doesn’t say so, there would also have been a constant flow of live, on the spot, mood-making background music, perhaps even “the Empire Orchestra,” under the direction of “Miss Muriel Porter,” who was in fact the wife of the owner, Charles Porter. Muriel was by no means in the background. She was also the theatre’s treasurer and would soon take over as proprietor — one of perhaps only two women to have managed a Peterborough move theatre. (Ethel Jones at the Tiz-It in 1916—17 was the only other I’ve found.)

Afternoon and evening, all for a price of from eleven to seventeen cents (the equivalent, in 2018, of $1.44 to $2.22). No popcorn. You had to get your treats at a nearby confectionary.

It was the opening year of a decade, the beginning of the “Roaring Twenties,” “the Jazz Age.” The painful devastations of the Great War had been over for a couple of years. The Russian Revolution and the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 had created their own brands of turmoil, stirring up mixtures of political hope and, on the part of some, fear. To many, it seemed that a new age was dawning. Indeed, writing about the optimism surrounding technological progress and the soon to come transition to sound movies, cinema historian Donald Crafton noted that the phrase “New Era” was “heard everywhere in the twenties.”

The March 1920 program of the Empire Theatre reflects this new time. After a long period of struggle women were gaining ground in efforts to assert their rights – they had won the right to vote in Manitoba in 1916 and British Columbia and Ontario in 1917 and federally (with some exclusions) in 1919.

Moving Picture World, July 11, 1914, p.195. Alice Guy-Blaché (also known as Alice Guy or Alice Blaché), born in Paris in 1873, became the head of production of the French Gaumont film company in 1896 and a pioneer director — from 1896 to 1906, says Alison McMahan, “probably the only woman director in the world.” She later moved with her husband to the United States and founded her own production company there. She made films until at least 1920 and returned to France in 1923.

The gains were as apparent within the Hollywood movie industry as they were elsewhere. “Women were more engaged in movie culture at the height of the silent era than they have been at any other time,” Shelley Stamp points out in a study of “Women and the Silent Screen.” The writer of Experimental Marriage was Alice Eyton, who fashioned scripts for 16 films from 1919 to 1922. She was only one of a great number of female screenwriters during the period – but then, women were working at all levels of the industry, and as more than just stars and extras. They were prominent as directors (including, at one point, the highest-paid director) and heads of photography and editing departments. There were many, like Muriel Porter, who ran movie theatres. Women were pioneering movie reviewers, too, like Peterborough’s Cathleen McCarthy, writing for the Examiner in the 1920s. It was a time, Stamp says, “of rapidly changing gender norms and shifting sexual mores.”

As early as 1914, the magazine Moving Picture World took care to emphasize that women should be mindful that they had a “place in photoplay production.”

Motion Picture News, Sept. 23, 1916, p1850.

Motion Picture Magazine, February 1918, p.36.

The ascendancy in the business was, of course, not to last. In more recent decades women have been severely underrepresented in key positions in Hollywood. As the documentary movie This Changes Everything (2018) points out, in the past three decades only 0.5 per cent of directorial assignments went to women. In this age of the #MeToo movement the accounts of misogyny, sexual abuse, and assault in the industry are rampant.

Although there were many women working in the industry, all was not well; and it would get worse over the years. “The Absence of Canadian Women in the Silent Picture Industry,” from Women Pioneers Film Project, “a scholarly resource exploring women’s global involvement at all levels of film production during the silent film era.”

*****

For women, and men, the questions the ad asked were controversial. “Ladies: How much freedom should a woman be permitted after marriage? Gentlemen: Would you marry a woman if you could live with her but three days a week?”

Moving Picture World, April 5, 1920, p.11.

The comedy Experimental Marriage had been released by Select Pictures Corp. a year earlier, in March 1919. It’s an interesting screening. This particular motion picture, writes Kay Sloan in “Sexual Warfare in the Silent Cinema,” marked the end of a long “film debate over suffragism.”

I have to admit I haven’t seen the film. It is considered to be “lost,” like an estimated 75 percent of silent films produced before 1929. But based on the evidence we have, the plot revolves around a young woman, played by Constance Talmadge, who wants to marry a lawyer, played by Harrison Ford, a handsome, dashing leading man (who was, of course, not the handsome, dashing Harrison Ford of more recent years). Although the woman would like to marry, she also wants to continue her work in the suffrage movement. That appears to have been a bit of a problem. As a plot description puts it: “Because he does not want to lose feminist Suzanne Ercoll, lawyer Foxcroft Grey unhappily accepts her proposal that they marry but live together only from Saturday until Monday, leaving each free to live as he pleases the rest of the week, no questions asked.”

Lobby card, 1919. Thanks to Doctor Macro website, http://doctormacro.com.

Marriage and a career, then, belong in separate worlds. When it comes to gender, the pronoun “he” towards the end of that sentence (in “as he pleases”) is revealing in itself.

As the movie twists and turns, complications and comedy ensue. A report from a press screening noted that almost continuous “ripples of laughter” were heard, and I would imagine that Peterborough audiences were similarly responsive. In the end conventional marriage, not surprisingly, wins out. (After all, the director of Experimental Marriage was a man; and so too were the moguls who ran Hollywood — and the key figures in Select Pictures Corp. were industry giants Lewis J. Selznick and Adolph Zukor.)

“Overt power” for women, Kay Sloan concludes, “would remain unacceptable for women in the decades to come.”

**************************************************

A Globe and Mail headline almost a century later: “Putting Oneself First: Still a Revolutionary Act for Women” (Sept. 21, 2018).

And another: “How Some Long-term Committed Couples Avoid the Daily Grind of Traditional Marriage by Living Apart” (Sept. 24, 2018).

**************************************************

The Darkest Hour poster, IMDb.

The other feature presentation, The Darkest Hour (released by Vitagraph in December 1919, and also considered lost), was a more typical melodrama of the era, but also had the dangers of marriage as a theme. The Empire’s ad gives only the title, but theatre managers would have received a number of possible publicity captions, including: “Can a Woman Make a Man Propose to Her Without His Having Any Knowledge of It?”

Motion Picture World, Dec. 6, 1919, p.661. A woman in overalls, just like the man.

In this case a wealthy (but very nice) man, Peter Schuyler, is more or less proposed to by a scheming woman who plans to divorce him quickly, get his money, and go off with the man she really loves (shades of an early film noir?). Before that can happen, thieves enter his house one night and give him a nasty bump on his head. He comes out of it with amnesia and wanders off to work in a lumber camp without any idea of who he is. In the camp he falls in love, of course, with his boss’s niece. He marries her – and then gets another bump on the head.

Now the unfortunate man remembers who he was before, but can recall nothing about the lumber camp and his marriage. He goes back to New York . . . Okay, that’s enough of the plot. It all ends well, but, as a review of the time noted, it is a “rather improbable story” although “entertaining enough so long as all of the incidents of the story are accepted without question.”

Finally, for something completely different, the Empire screened a “Canadian Government Scenic.” The short film was probably issued by the federal Exhibits and Publicity Bureau, established in 1918 within the Department of Trade and Commerce (and re-branded as the Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau in 1923). The Bureau’s films, aimed at promoting various sectors of Canadian life and industry, were being distributed widely to theatres through the big Canadian Universal company.

A “scenic” was considered to be educational: a view of a natural phenomenon such as Niagara Falls or the Rockies, for instance; or films of the fisheries or of an industrial operation. They were what historian Peter Morris calls “idyllic portraits of Canada.” Typical titles around that time were The Most Picturesque Spot in North America, Lake Louise; Wooden Shipbuilding in Canada; Building Airplanes in Canada; and Harvest of the Sugar Maple Time. The Empire audience would have seen something along those lines, and it was unusual fare. Local movie-goers seldom had a chance to see themselves or their own country depicted on-screen.

*****

Examiner, April 28, 1921, p.11.

As for the Empire Theatre, about a year later, in April 1921, it brought people out for the six-reel The Tiger’s Coat (1920), which featured among its cast yet another notable woman of the time: Tina Modotti. Described in a local news piece (“Moditti”) as a “piquant little Italian beauty,” Modotti had actually left Italy in 1912 to go to the United States. She made only two or three films before moving in 1922 to Mexico. There, as a photographer and photojournalist (and member of the Communist Party) she became part of an artistic and political community that included the painters Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. In the 2002 movie Frida, starring Salma Hayek, Tina Modotti was played by Ashley Judd. Award-winning Canadian filmmaker (and friend) Brenda Longfellow also made a documentary, Tina in Mexico (2002), that uses re-enactments, newsreel footage, and Tina’s own observations, journals, and photographs to tell her story.

Lobby card, 1920, IMDb.

Up the street and around the corner, at the Regent on Hunter, the attraction that same day was (confusingly) The Tiger’s Cub (1920), “a tale of daring and thrilling romance in faraway Alaska.” The film, yet another now lost, featured one of the two or three most popular female stars of the time: the resourceful and athletic “serial queen” Pearl White (of Perils of Pauline fame). White had appeared in several serials and was known for doing her own stunts. The popular serials of the 1910s tended to have female leads, “renowned for their stunts, physical power, and daring,” said historian Lewis Jacobs, writing in 1939. “Their exploits paralleled, in a sense, the real rise of women to a new status in society.”

The Tiger’s Cub was a feature film and not a serial – and, judging from this lobby card, represented women in a more conventional fashion.

Both of the “Tiger” films screened on April 28, 1921. The very next day the Empire Theatre closed down forever, after less than seven years in action.

****

Sources

Peterborough Examiner.

Moving Picture World.

American Film Institute and IMDb entries for the films.

Donald Crafton, The Talkies: American Cinema’s Transition to Sound, 1926–1931 (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1999).

Richard Koszarski, An Evening’s Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915–1928 (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1990), pp.271–73.

Lewis Jacobs, The Rise of the American Film: A Critical History (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1939), p.279.

Peter Morris, Embattled Shadows: A History of Canadian Cinema, 1895-1939 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1978), pp.134, 135.

Kay Sloan, “Sexual Warfare in the Silent Cinema: Comedies and Melodramas of Woman Suffragism,” American Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 4 (Autumn, 1981), pp.412–36.

Shelley Stamp, “Women and the Silent Screen,” in Wiley-Blackwell History of American Film, ed. Cynthia Lucia, Roy Grundman, and Art Simon, 1st ed. (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishing, 2012), Wiley Online Library, pp.16, 22.