The Jazz “Age of Amusement” – Not to Everyone’s Liking

“One of the most pleasant sensations to the average theatre-goer is the one experienced while sitting in a comfortable chair and watching a real, honest-to-goodness thrilly picture that goes in for midnight murders and secret panels and sudden disappearances of main characters.”

Examiner, Nov. 30, 1925, Jan. 15, 1925.

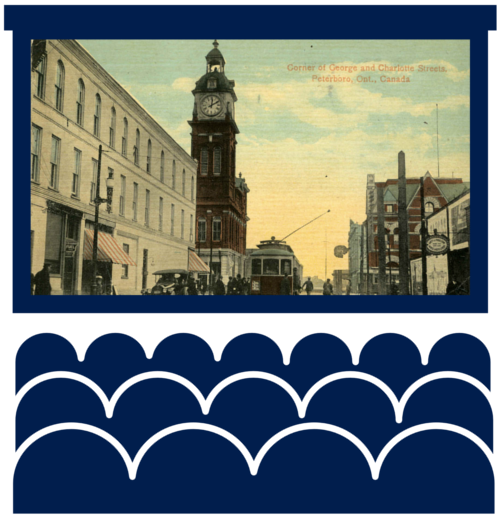

By the 1920s a mass audience was appreciating the thrills and spills of the modern moving picture show. People in Peterborough could see movies daily at the Capitol and Royal theatres on George Street, the Regent on Hunter, and occasionally, too, at the city’s most prestigious spot, the Grand Opera House.

The public was being served – and in this hockey town people could catch up with the scores of that night’s game. The Royal, Capitol, and Regent all made a point about announcing hockey scores in the 1920s, and the added feature proved a big draw. In February 1926 Peterborough’s Austin Nixon wrote in a letter to his girlfriend: “Oh boy, I was up at the Regent Thurs night with Monty of course to hear the results of the Parkdale vs Petes Hockey game.” A few months later he commented, “. . . looks as if Peterboro is going to win the Senior O H A. The final game is Tues night in London & the big feature of the week is trying to get in the Regent Tues. night.” In other words, with hockey scores being announced, the theatre was being packed to the doors. “At 6:30 Friday night there was a line up right to George St. from the Regent & crowd broke the glass doors . . . when they opened the doors. They had four Cops there. Patsy O’Keefe & I were there at 6:25 & got a seat & we’re going up at 6 to-morrow night so we hope to get in.”

Examiner ad, April 29, 1925.

Live and local music was also a big draw. Everyone got a chance to perform at the Royal Theatre’s amateur night, and the audiences, by all accounts, loved it – from the six-year-old Annie Fletcher to three rounds of staged fisticuffs.

*****

Not so enamoured of the local entertainment scene, though, was Peterborough’s Chief of Police, Samuel J. Newhall.

Examiner, Sept. 23, 1907, p.5. A young Sam Newhall, after reporting on a trip across the Atlantic and back.

By 1927 Newhall had been on the force for twenty-one years. He had first worked as a bobby in London, England, in 1897 before taking a position in Liverpool, serving on the force there until 1904. He had done policing in Cuba before taking a position in Peterborough in June 1906. At that time, under Police Chief George I. Roszel, the contingent had four constables. In January 1911 Newhall was promoted to “plain clothes duty,” becoming a detective and later a detective sergeant. He ascended to the position of police chief in 1920.

By 1927, under Newhall, the force had twelve men and a “matron,” Miss A. Wood. Newhall, it was said, “ruled the force with an iron hand.”

In November 1925 Newhall went public to express concern about what he saw as a “crime wave” sweeping the world – and its repercussions for Peterborough. One day in the pages of the Examiner he expounded on the “irresponsibility of youth of the present age.” He placed the blame firmly on a disregard of authority and what he saw as a failure of proper parental guidance.

“In this age of amusement,” he argued, parents were all too “willing that their children should frequent dance halls and boot-legging joints.” The dance halls, he said, provided “a legitimate excuse to remain out until a late hour.” In his mind the proliferation of “motor cars” was also not a good thing.

Meanwhile, he huffed, the parents, “with their responsibility lifted from their shoulders, go to a movie show.” The chief clearly saw the silent motion pictures of his day as a frivolity distracting from the important stuff of life.

Another thing: the children under age sixteen who were out at night were lying to the police about their age; with no law requiring birth certificates, the police couldn’t check the truth of their statements.

Examiner, Nov. 3, 1925, p.11. Imaginative advertising.

Parents, Newhall said, needed to step up and take charge. Until then they were only being “selfish, as their carelessness was due to a desire to gratify their own desires of pleasure.” A U.S. sociologist, writing around the same time, pointed his finger at much the same thing, arguing that “more of the young people” in his day were “sex-wise, sex-excited, and sex-absorbed than of any generation of which we have knowledge” – and this sad state of affairs was largely due to “their premature exposure to stimulating films.” This new age was indeed not to everyone’s liking.

Perhaps most significant, though, was the Royal Theatre’s response. The management took note of Newhall’s message and jumped at the prospect of using the chief’s words for its own purposes. In an ad the very next day the theatre announced, “The Chief is Right!”

The movie currently playing, Cheap Kisses (1924), with its own message “thundering” across the screen, apparently just happened to prove his point. “The seeming lack of decorum and decency in some of the younger generation is due to the lack of home training!” said the ad for the film.

Well, then, parents did need to go off to the movies and educate themselves. Moreover, the Royal invited any mother or father in Peterborough who couldn’t afford the movie to come along, free of charge – “Everything will be strictly confidential.”

According to one review, condemning it with faint praise, Cheap Kisses had “considerable jazz atmosphere for those who like it, and the story runs along smoothly.” The film, a mix of comedy and drama, told the story of “a chorus girl of excellent character who marries into a wealthy and snobbish family and,” according to the article, “gets a taste of the sham and artificiality and cheap morals of certain persons of that type.”

For those who went out that evening, the movie might have made for an enjoyable evening – indeed, gratifying “their desires of pleasure” – but it was not likely to have delivered a message that would alter their lives. The theatre’s advertising was inventive, to say the least – and in the 1920s the promotion of films became an art in and of itself.

Sources: “Back to His Beat after Visit to His Former Home,” Examiner, Sept. 23, 1907, p.5; “Chief on Force for 30 Years,” Examiner, Tuesday, Jan. 25, 1927, p.1; Peterborough Directories, various years; “Two More Men for Local Police Force,” Daily Review, Jan. 24, 1911, p.8; G. Wilson Craw, The Peterborough Story: Our Mayors 1850-1951 (Peterborough, n.p., 1967), pp. 107,112–13, 143; “Many Motors in Peterboro,” Examiner, Aug. 3, 1925, p.11; “Chief Newhall Holds Parents to Blame,” Examiner, Mon, Nov. 2, 1925, p.1; U.S. sociologist quoted in Sklar, Movie-Made America, p.137; “Cheap Kisses,” Motion Picture World, Nov. 15, 1924, p.269; Examiner theatre ads, Jan. 15, 1925, Feb. 13, 1925, April 29, 1925, Nov. 3, 1925, Nov. 4, 1925, Nov. 30, 1925.