Glimpses of the Early Movie-Going Audience in Peterborough

Peterborough Examiner, March 18, 1914, p.10. Direct from Italy, among the first “big” pictures to come to town — and one of the first big ads complete with an image. “Your money back if not satisfied.”

From women and children to a supposedly ne’re-do-well Irishman – from visiting Roma to a famous local Mississauga Ojibway athlete and his wife – from the teenage working-class Cathleen McCarthy to the Grants, a relatively well-off family – attendance at early motion pictures shows a surprising diversity.

In the early years of the twentieth century, the new marvel of motion pictures quickly caught on in Peterborough – just as it was doing elsewhere around the world.

Newspaper articles and ads of the time indicate where motion pictures were screened. But just who went to the pictures in those days?

News articles tell the stories of a supposedly ne’re-do-well Irishman and visiting Roma who were strangely attracted to the moving pictures. On at least one occasion Fred Simpson, a famous local Mississauga Ojibway athlete and his wife, went to the Royal Theatre to take in the program. And two diaries in the Trent Valley Archives provide evidence of how, for an older professional man, going to the cinema was a special event; and of how a young Cathleen McCarthy went to the cheaper theatres on an almost daily basis.

*****

At the very first the new “amusement” was something of a “novelty” – “the cinema of attractions,” it has been called – and people often went to see the shows out of curiosity: “Wow! Pictures that move! So life-like! Amazing!”

From 1907 on, movie theatres were a fixture alongside shops, department stores, and offices in downtown Peterborough – although at first they were often short-lived, makeshift storefront enterprises that, based on their ticket price, were called “nickelodeons.” For a while the pictures were referred to as “the poor man’s amusement” (although records reveal that women and children often made up the primary audience).

Examiner, Jan. 27, 1914, p.1.

Given the low price, of a nickel (the cost of a street-car ride), women (sometimes with their children in hand) could easily pop into a theatre for a half-hour or forty-five minutes (the length of the short program) when they were downtown doing shopping or engaged in other daily activities. As the theatre ads often said, “Come when you like and stay for as long as you like.”

Although many people soon “contracted the movie-going habit,” not everyone would admit to it at first. For a while, as the eminent Canadian film historian Peter Morris noted, “Movie theatres were not places in which respectable people cared to be seen. Educated people still considered the movies vulgar, low-class entertainment.” But quickly, what was at first seen by many as a “passing fad,” by some as dangerous, and by others as even a little childish quickly became a “major part” of the city’s social life.

Still, as the records show, from the very first “respectable” people in Peterborough did go to see the short silent films of the time, whether in church and community halls or outdoors on a grassy slope in Jackson Park (in summers from 1905 to 1908). Despite reservations, people from across all classes went to the early pictures – including special showings at the Grand Opera House and more often regular films at the small dedicated theatres of the time. Opera houses like the one in Peterborough offered a scale of prices that accommodated a wide audience, and we know from the survival of theatres as commercial enterprises that “large audiences” turned out on a regular basis.

Newspaper articles provide a few glimpses of the audience. In 1907, for instance, a young Irishman named David Hoben (described only as “a frequent offender”) appeared before a judge after creating a disturbance at the storefront “Coliseum” at 432 George Street (the site today of Christensen Fine Arts and Framing). This appears to have been the paper's misspelling of the name of David "Hoban," identified as a “lumberman,” who lived briefly at 715 George Street. Apparently Hoben had been so offended by what he saw on screen – a “picture of Highland troops” – that he let out “an unearthly yell.” The account doesn’t explain exactly why he did that, but it was enough to land him in court the next day.

When the famous group of “gypsies” (more accurately, Roma) were in Peterborough in June 1909, camping on the southern outskirts of town (in what is now the area of King Edward Park in the south end), they decided to take in the pictures at the Crystal Theatre at 408 George Street. They had heard that a film about “Mexican gypsies” was being shown. Some seven or eight of them walked up to the theatre, which was on the east side of George just north of Hunter (where “The Peace Pipe” store is located today). The newspaper (reflecting the conventional prejudices of the time) emphasized how the “entire contingent” somehow got into the theatre by paying only a nickel in total – and how even so they became “indignant” and “kicked up quite fuss because they didn’t see the picture” (it had closed the previous evening and been sent back to the film exchange).

One winter afternoon earlier that same year the Mississauga Ojibway “road-runner” (and 1908 Olympian) Fred Simpson, born on the nearby Alderville reserve, made a cameo appearance at the Royal Theatre at 348 George St. (where Peterborough Square now is). Simpson was something of a local celebrity, and the matinee audience, according to the newspaper report, gave him "a great reception."

Peterborough Examiner, Sept. 18, 1908. One day Simpson dropped into the Royal Theatre to see a film.

In those days a “lecturer” was often present, standing up near the screen, to explain what was going on in the silent films; and in this case the lecturer took the opportunity to introduce the well-known runner to the audience. Simpson had just won great honours as ten-mile champion of the world, and, indeed, the Examiner, in a typically racialized representation, referred to him (somewhat proudly) as “the Peterborough Indian.” The local hero (later to become a member of the Peterborough and District Sports Hall of Fame) was introduced to the guest vocalist, Marguerite Walsh of Boston. He told her how he had just been in Savannah, where the temperature was "26 in the shade." Simpson was accompanied by his wife, Susan (Muskrat) of Hiawatha, and at 4:00 p.m. they left to make a visit to her home at Hiawatha on Rice Lake.*

*For an interesting study of “how ideas about race were embedded in and conveyed through” the Examiner’s coverage of Simpson, see Janice Forsyth, “Out of the Shadows: Researching Fred Simpson,” University of Western Ontario, 2010, http://library.la84.org/SportsLibrary/ISOR/isor2010t.pdf.

Examiner, Feb. 25, 1909, p.1. What Fred Simpson went to see at the Royal.

Fred Simpson, Balsillie Collection of Roy Studio Images, Peterborough Museum and Archives, 1907.

Other more in-depth examples of attendance in the earliest days are difficult to come by; but the McCarthy and Grant dairies are revealing – and especially because they represent people from very different social milieus. One of them, running from December 1905 to October 1909, was written by a young office worker in a downtown store; and the other by a well-to-do man who lived in Peterborough from 1906 to 1919.

The McCarthy Diaries

The first page of Cathleen McCarthy's diary. Trent Valley Archives.

Cathleen McCarthy, born in 1889, lived in Peterborough from around 1900 to her death in the early 1980s – and, perhaps most notably, had a distinguished career as a reporter (and society page editor) for the Examiner in the 1920s and 1930s – including a stint as movie reviewer.

In her diaries the teenage Cathleen McCarthy gives a vivid account of the day-to-day events of her life. She went almost every day to the Total Abstinence Society’s “Rooms” (where her mother worked) for tea. She loved ice cream sodas and sundaes, skating and tobogganing, and motion pictures. (For a while she spelled her first name "Kathleen" before changing it to "Cathleen." In her diary, for some reason, she spelled her last name "MacCarthy" although the family name was "McCarthy.")

McCarthy’s diary entries indicate that she went with remarkable regularity to the theatres. She attended the Grand Opera House (established 1905), usually for live performances rather than motion pictures; and frequented the Crystal (her favourite place, est. 1907), the Royal (est. 1908), and the Princess (est. 1909), all of which featured both films and live acts or music. At times she went on an almost daily basis – as, for example, during the week of Aug. 20 to Aug. 27, 1908, when she went to “the pictures” no less than six times (and the theatres were closed on Sundays). On one of those days, Friday the 20th, she went to both the Crystal and Royal, but that was not an isolated occurrence: in 1909 and 1910 she went to more than one theatre on the same day 12 times. She enjoyed the Labour Day holiday, 1910, by going in succession to the Royal, Grand Opera House, and the Princess.

A young but avid motion-picture-goer Cathleen McCarthy. TVA.

She often went with her sister and a few times with her mother; sometimes with friends from work or with her closest friend, Evelyn Dorris, who worked at Cressman’s department store. A typical note would be: “We all went over to the Crystal, after” – which meant “after” finishing work (which on Saturdays was at nine p.m.), or having tea, usually at “the Rooms,” or shopping, or a music lesson. In one month alone, July 1908, for instance, Cathleen “went over” to the Crystal eight times (while also going to view the “pictures” at Jackson Park a couple of times too). Sometimes after the pictures she and the others stopped into Hooper’s (a bakery and confectionary store on George Street) for ice cream, or they had “tea at the Chinaman’s.”

In summer 1906, Cathleen went to see the evening “pictures” at Jackson Park ten times. The first time she recorded this event was June 6. Following her “second [violin] lesson at the Conservatory,” she then “Went down to the Rooms after, & went out to the Park, to see the moving pictures.” She was sixteen years old, and had been working at Frank R.J. MacPherson’s plumbing and electrical supplies shop on George Street since age fourteen. Her family was not rich, but she had a little spending money and a budding air of independence.

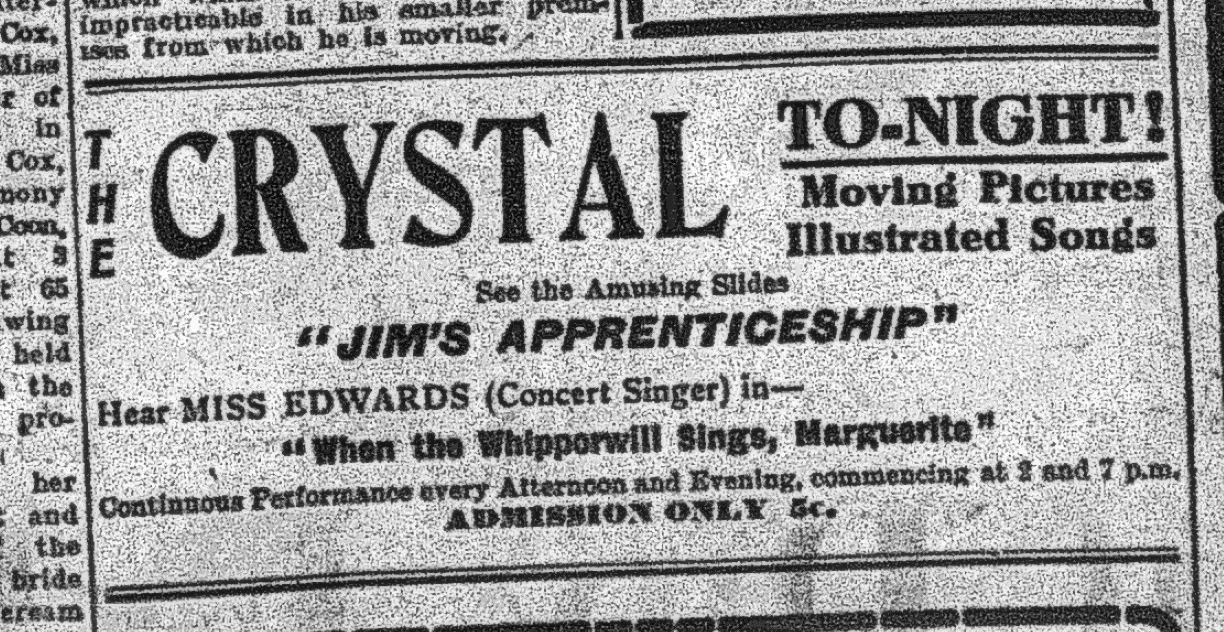

The first visit she recorded to the Crystal Theatre was on Oct. 10, 1907, shortly after it opened. In December she went there with a friend to see “The Passion Play” – “the first part of it.” On the last day of February 1908 she wrote, “Had a lesson to-night & Evelyn and I went down to the Crystal, after.” A few weeks later, on Friday, March 13, it was: “Evelyn & I were to go for a lesson, to-night, but we went to church, & then went down to the Crystal, & Got back too late.” (Her mother was upset.) Other than The Passion Play, in her diaries the only other titles she mentioned seeing were Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Macbeth. One time she commented, after going to the Crystal, “It’s rather amusing.” Another time, after going with her mother and sister, she said, “It is very good!” And, on Oct. 7, 1908, about the Crystal: “It is a fine little place.”

In those days, too, the attraction was not just the latest in silent moving pictures. There was more going on – in addition to a “lecturer” there was plentiful live music for the nickel admission, usually at least a pianist, sometimes a small orchestra – and at times a “trap drummer” produced sound effects to go with the film.

Peterborough Examiner, Sept. 25, 1907, p.5.

On the evening when Cathleen McCarthy first went to the Crystal she would have enjoyed “Miss Edwards” (the daughter of the owner) singing one of the song hits of the day, “When the Whippoorwill Sings, Marguerite,” among other delights. As Canadian film historian Peter Lester points out, in the era of early silent films, “spectating” was “but one of numerous activities. . . . Audiences listened, engaged, participated, sang, discussed and basically interacted with one another.”

The Grant Diaries

The Grant diaries provide quite a different angle on movie-going, one involving a family of a different social class. They indicate that, while going to the live “theatre” remained the most common form of amusement for the Grant household, Alexander Grant and his wife did, from time to time, make their way downtown to attend motion pictures. In his study of audiences in a small U.S. city in the early days, U.S. film scholar Roy Rosenzweig noted an “expansion of movie-going into the city’s middle class,” and it seems that this tendency was true for Peterborough as well.

Grant had arrived from St. Catherines in April 1906, at age forty-three, to take up a well-paying job as superintending engineer of the Trent Canal system. With wife Maude and young son Alex (adding a daughter, Helen, in 1908), the Grants had an income that allowed them, within a year, to buy a large house on a big lot at what is now 580 Gilmour Street, about a twenty-minute walk from downtown – or a quick trolley ride. (They purchased the house for $5,600, with $2,100 down.) Their everyday life as recorded in Grant’s diaries offers a good example of how the middle class enjoyed the “amusements” of the day.

Alexander Grant and his wife, Maude, on their wedding day. Balsillie Collection of Roy Studio Images, PMA.

With their active social life the Grants appear to have been typical. They gathered with friends for “teas” and card-playing, attended a few lectures, went on summer excursions to nearby lakes, and, with their youngsters, took in the circuses that passed through most summers. One evening they went to the “Peterboro club dance” at the Conservatory of Music. Grant himself took up curling in 1911, exercised at the YMCA, and did a little golfing. He joined the Peterborough Horticultural Society. In 1917 he bought his first automobile, an Overland Touring Car, from Banks Garage for $930.

Most significantly (for our purposes), the diaries reveal that over the period of 1906–19 one or more of the Grants went to what has been thought of as the “legitimate theatre,” with its live performances, at least forty-two times – and attended the new “motion pictures” only twenty-two times. (These numbers include theatre- and movie-going both in Peterborough and in places visited outside Peterborough.) For people like themselves, of higher income, then, going to the theatre was still the primary cultural thing to do, and something of a routine; they went to the motion pictures much less often.

Still, that they did go to the pictures at all, and to the extent they did, is telling: by the 1910s “going to motion pictures” (they were not yet called “movies”) was obviously deemed a proper pastime for such folk. It also became more customary as time went on. After only a very few visits to the motion pictures in the years 1906–14 (7 outings in nine years, not including a night at the Grand Opera House to see “Crocker’s horses,” a program that included films, but with the horses as the main draw), the Grants went to the pictures twice as much – 14 times – in the five years from 1915 to 1919, making 21 times in all.

In contrast, according to her diaries, Cathleen McCarthy visited motion picture theatres 203 times from 1906 to 1910. That doesn’t include events at the Grand Opera House (38), which sometimes (though not often) included motion pictures.

In 1906 and 1907 the Grants were also, like Cathleen McCarthy, among the large crowds attending motion pictures outdoors at Jackson Park. In January 1909 they were curious enough to go out to “the new theatre, the Royal,” then a month old. After that, they didn’t take in another picture for three years, when they joined the diverse audience that must have greeted the extremely popular motion picture “Rainey’s African wild animals” at the Grand Opera House in January 1913. They were at the Grand for the spectacular (and Italian) Last Days of Pompeii (Gli Ultimi Giorni di Pompei, Italy, 1913) in February 1914; and they went to see what the Empire Theatre was like a few days after it opened on Charlotte Street in summer 1914. Later on, in the fall of 1916, they saw Sergeant Wells and the “Canadian Moving War pictures” and two other war films (including The Battle of the Somme). They went to the Empire two more times and took in D.W. Griffith’s grand extravaganza Intolerance (U.S., 1916) at the Grand Opera House in March 1917.

Their picture-going was limited to the Opera House, the Royal, and the Empire. There is no indication that they went to the “cheaper” theatres (the Crystal and its successors, the Red Mill and the Strand; the Princess or its successor, the Tiz-It). It appears that they did not go to motion pictures as a diversion or distraction, but more as an occasional special “event.” They went out of curiosity to witness the opening of a new theatre, as marked by their outings in the case of the Royal and the Empire.

Presentations of Uncle Tom's Cabin, as both live theatre and motion pictures, were regular features in the first two decades of the twentieth century. This "newest edition of the Oldest Hit" came to town in January 1912.

The more established live “theatre” remained their first love. Their dates at the Grand Opera House included live performances of Macbeth, by the Ben Greet Players (November 1907); Coming Through the Rye (March 1908); Il Travatore, Carmen, and The Merry Widow (1909); Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Dockstader’s Minstrels (1910); and She Stoops to Conquer, with the famous British stage actress Annie Russell (1913). They saw the English actors Tom Ferris (doing Dickens in January 1914) and John Kellerd (in Hamlet, 1916); and many, many more. A highlight might have been the Oscar Wilde play Salome in February 1909, “from the wonderful brain of the brilliant but erring Oscar Wilde,” as the Examiner noted. Including its notorious “dance of the seven veils,” the performance apparently “pleased [a] large audience,” and “Peterborough people failed to find anything objectionable in the much talked of play.”

Moving Picture Theatres: “An Open Public Sphere”

Ironically, Cathleen McCarthy had gone to see at least two of the same attractions – Macbeth and Uncle Tom’s Cabin – but for her the experience was in the form of the less prestigious film as screened at the cheap motion picture theatre.

While McCarthy noted going to see the popular religious spectacle The Passion Play on film, as it turned out the very last local play the Grants attended in Peterborough was also of a religious bent. They went to see The Wanderer at the Grand in January 1919 – and Alexander Grant appeared not to have much liked it. He cryptically remarked on it as being “a representation of the ‘Prodigal Son’ B.C. 1200 – an immoral play.” He was no doubt responding to what one notice described as a play that “attracted chiefly by scenery, dresses, stage-mounting, and a picture of Oriental sensuality and voluptuousness.” The Peterborough theatre audience was no doubt dazzled but perhaps also, like Grant, somewhat taken aback. Shortly before the play came to the city, in London, Ont., it was billed as “the biggest spectacle ever brought to London with a flock of real sheep, dogs and goats, and a large ballet of dancing girls.”**

As a whole Grant’s diaries – that of a relatively well-off professional (and family) man – indicate that, while going to the live “theatre” remained the most common form of amusement for his household, he and his wife did, from time to time, make their way downtown to attend motion pictures.

Indeed, as Rosenzweig puts it, film-going would quickly become “the first medium of regular inter-class entertainment” – and this would particularly be the case as the exhibition of motion pictures moved into larger, more respectable venues built specifically for the purpose. The cinema was becoming “an open public sphere.” Film historian Charles Musser goes even further, arguing: “From the outset . . . the cinema drew its audience from across the working, middle, and elite classes.” It is very likely indeed that on many occasions the Grants and McCarthies and their friends were all there together, taking in the same pictures (and music) in the same theatre at the same time.

** The Wanderer company was said to consist of 55 people and used two baggage cars on its travels from place to place. “Shows Opening,” Variety, Nov. 8, 1918, p.22. The play had previously played in Toronto and Montreal.

Sources

Books: Peter Morris, Embattled Shadows: A History of Canadian Cinema, 1895-1939 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1978), p.23; Roy Rosenzweig, “From Rum Shop to Rialto: Workers and Movies,” in Moviegoing in America, ed. Gregory A. Waller (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers, 2002), pp.29, 39; Charles Musser, The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907, vol. 1, History of the American Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994 [1990]), p.183; Heather Y. Shpuniarsky and the Village of Hiawatha Book Committee, The Village of Hiawatha: A History (Hiawatha, Ont.: Ningwakwe Learning Press, 2016), pp.106–7, 201.

Newspaper articles: “Scottish Picture Aroused Spectator,” Daily Review, April 25, 1907, p.4; Daily Evening Review, June 28, 1909, p.4; Evening Examiner, Feb. 25, 1909, p.17; Evening Examiner, March 3, 1909; Crystal ad, Examiner, Sept. 23, 1907, p.5 (although the ad spelled it “Whipporwill”); “ ‘Salome’ Pleased Large Audience,” Evening Examiner, Feb. 18, 1909, p.7.

For "Hoban," Peterborough City Directory, 1907, p.165.

Also: Elwood Jones, The Gypsies That Visited Peterborough in 1909, Occasional Paper no.21, Peterborough Historical Society, February 2001, p.10; Peter Lester, Cultural Continuity and Technological Indeterminancy: Itinerant 16mm Film Exhibition in Canada, 1918-1949,” Ph.D. thesis, Department of Communication Studies, Concordia University, 2008, p.21 (Lester is citing Miriam Hansen, Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1991), p.93); (for The Wanderer) “The Stage” Year Book, 1918, ed. Lionel Carson (London: “The Stage” Offices), p.30, and London Free Press, Wed. Jan. 8, 1919, p. 10; cited in “The 78 RPM Record Spins,” The Starr Company of Canada, London, Ontario by Betty Minaker Pratt (courtesy of the APN, 2008), https://the78rpmrecordspins.wordpress.com/2013/02/25/the-starr-company-of-canada-london-ontario-by-betty-minaker-pratt-courtesy-of-the-apn-2008.

For the motion picture as “childish,” see “Picture Shows Popular in the Hub,” Moving Picture World, May 16, 1908, p.433.

The diaries: Fonds 572, “Cathleen McCarthy,” Diaries, Trent Valley Archives. (Although she spelled her name as “Kathleen MacCarthy” on the first page of the diary, the correct spelling as time went on was “Cathleen McCarthy.”) For Alexander J. Grant, 1906–1919 diaries, see the Heritage Gazette of the Trent Valley, running from vol. 12, no.4 (February 2008) to vol. 16, no.3 (November 2011).