From Buffalo Bill to Oklahoma Jack: The Wild West Tries to Come to Peterborough

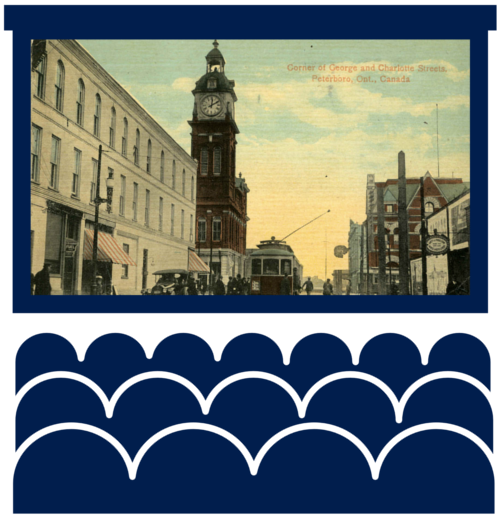

A wintry day on George Street, December 1910: a case study in early local motion picture publicity. Peterborough Museum and Archives (PMA), Balsillie Collection of Roy Studio Images, 1978-012-40A-44.

The Crystal Theatre, 408 George Street: a typical storefront theatre (or nickelodeon) on the main street, embedded in a stream of commercial interests in the heart of downtown. One one side, to the north, an optician (C.A. Primeau), the Boston Café, and a butcher, David W. Porter. On the other, to the south, a shoe store (J.W. Miller & Sons) and the Peterborough Music Co. Upstairs above the Crystal were offices for the Division Court Clerk, the American Consular Agent, and a dentist, plus the Belmont Club and Foresters Hall. A busy place, and especially so on this Saturday.

A Buffalo Bill (of Sorts) Comes to the Crystal Theatre, December 1910

This previously undated photo of the Crystal Theatre on George Street (just above Hunter) must have been taken on Saturday, Dec. 10, 1910. It was a frosty day, with the lowest temperature of the winter so far, and a big snow storm on its way. The winter that year had begun on Oct. 28 — and it was followed by five months of snow and cold that would last until at least March 31.

Examiner, Dec. 9, 1910, p.9. Poor quality, but just for the record: the one newspaper ad I have found for the show.

This frozen-in-time display was all about the arrival of the famous Buffalo Bill – both on film and in the form of an inebriated impersonator.

That particular Saturday in Peterborough was witnessing a goodly number of events. Those stepping out into the cold could find comfort, perhaps, in the crowded warmth of the Royal and Princess motion picture theatres, where in addition to adjusting their eyes to the flickers they could listen to the singing of Mr. (Albert Victor) Loftus, “a fair-haired young Irish lad with a silvery tenor voice” and a regular performer at theatres over a number of years. The Royal that day had “as many as six vaudeville artists” on its stage – “high-class entertainment at the cheapest possible figure.”

The Grand Opera House down the street was staging a live, Canadian drama “of the woods,” The Wolf, the big “hit” of the previous season — a big success at the Lyric Theatre in New York City, with a special matinee price of 25 cents for any seat — and there were motion pictures being shown too.

But beware: the Examiner that same day issued a most serious warning headlined “Cigarette Heart and the Moving Picture Eye.” Based on a report out of Ottawa related to issues of naval recruiting, the article told how some 75 per cent of the young men coming to sign up from Nova Scotia and British Columbia were failing to pass eye examinations – and smoking and “frequent” motion picture attendance were at the root of the dilemma.

“The moving picture eye is a new peril of civilization. The effect upon the sensitive nerves of the eye, of frequent attendance at moving picture shows must be very great. Many people say that they have a headache after keeping the eyes fixed for a time on the constantly changing points of light that produce a moving picture, but the headache, like the tobacco stains on the fingers, seems to be only evidence of more serious trouble. . . . Is the moving picture eye to take a permanent place among the diseases of the modern world?”

A detail from the photo of the Crystal Theatre, Dec. 10, 1910.

No wonder Wesley A. Edwards, manager of the Crystal Theatre, saw a need to give his program an extra boost. It was a time when motion pictures had not yet been totally acclaimed as suitable for mass audiences — and a good deal of the publicity took place, day after day, out there on the street in the form of makeshift banners or loud, live presentations.

For all of those willing on this particular day to brave the cold and ignore thoughts of disease, the film showing at the Crystal was Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Far East (1910). If you look closely at the photo, you can see the poster there on the left side of the entrance.

In the larger photo, one of the young girls seems to be dressed as an “Indian.” One of the others might be “Annie Oakley.” The person on the small horse is playing Buffalo Bill.

The actor, as “Buffalo Bill,” on what was called a “charger,” outside the theatre. A detail from the larger photograph.

The display might have attracted an audience to the Crystal’s 200 or so seats (and did all those newsboys get in to see the picture?), but things did not go completely well that day. Edwards hired a “vagrant” named Edward Rickaby [also given as “Alfred Ricoby”] to dress up as Buffalo Bill and ride around the streets to advertise the film.

Rickaby came to the theatre at ten in the morning and became annoyed when his “charger” had not yet arrived. Eventually he (or perhaps someone else: the record is not clear on this point) must have mounted the steed, done a little riding around accompanied by the others, and posed for the picture. Rickaby later said that he waited around in the cold for his money ($1.50 to $2.00) from eleven until two in the afternoon but did not get paid.

At some point Rickaby entered the theatre. When Edwards showed him to a seat, Rickaby refused to sit down and began to create a nuisance. When Edwards asked him to leave, Ricoby resisted and was forcibly “put out.” Later Rickaby claimed that Edwards had grabbed him by the throat — and charged the theatre manager with assault.

The case was heard in court the following Monday. Defence witnesses testified that on Saturday Rickaby had been “rather the worse for liquor” and “under the influence.” One of them suggested that Rickaby had “toyed with the amber fluid.” Those on the spot agreed that the actor had not been assaulted at all; he had been asked to leave and then finally had been escorted to the door.

Daily Evening Review, Dec. 12, 1910, p.5.

Rickaby, the Examiner reported, “told his story in a very dramatical style and caused great amusement in the court.” Indeed, the Review, applauding “his delivery,” compared him to a character out of Shakespeare: “He orated like Hamlet. He had the ‘ha, ha, fair lady’ dope down to perfection. . . . He was truly majestic.”

When a female employee of the theatre was testifying about his behaviour, Rickaby became “very much annoyed.” He said to her: “ ‘Ha, ha, my dear girl . . . You are perjuring yourself.”

The judge was not convinced of the merits of Rickaby’s case. He dismissed the charge and presumably Rickaby left town shortly thereafter.

No matter: the show itself, and manager Edwards’s publicity, proved a success. Buffalo Bill Cody was an aging but well-known figure; many of the locals might have known that in the previous May he had drawn seven thousand fans to a packed Madison Square Garden in New York. In Peterborough, “The Buffalo Bill attraction at the Crystal,” the Review noted, “is proving quite a novelty and is drawing large crowds.”

*****

Circus poster for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, Wikimedia Commons and Smithsonian Magazine <www.smithsonianmag.com/history>.

I can see the headline on CNN – BREAKING NEWS! Buffalo Bill – the Man and the Legend – in Town at Last!

Although it’s not exactly “breaking news” (like most everything else on CNN), the imaginary headline is at least partly correct. Buffalo Bill was both a man and a legend, and he did come to Peterborough – more than once, in one way or another. And people tended to pay attention.

In addition to many appearances in highly fictionalized films – and that one time in the form of the supposed actor Edward Rickaby – he came at least twice to Peterborough in person with his famous wild west show: on Oct. 27, 1880, and July 3, 1897. (A non-Buffalo Bill pretender came to the city in the summer of 1911 in the form of the “Young Buffalo Wild West” show — with no involvement on the part of William F. Cody, but with the participation of the famous Annie Oakley.)

1880

Daily Evening Review, Oct. 23, 1880, np. Buffalo Bill’s Combination Acting Troupe, appearing indoors at Bradburn’s Opera Hall.

Daily Evening Review, Oct. 28, 1880, np. Gaining the “rapturous applause” of a large Peterborough audience. Unlike the ever popular minstrel shows, usually with white people in blackface, William Cody travelled with indigenous peoples in his act.

1897

Daily Review, June 18, 1897, p.4. Laying the ground for the July visit of the legend, W.F. Cody: he will indeed be present — and local audiences would see the same vast exhibition presented at the Chicago World Fair.

Daily Review, June 17, 1897, p.4, announcing the July 3 event.

Examiner, June 28, 1897, np. Other ads mentioned a covered grandstand able to seat 20,000 people, and the presence of Miss Annie Oakley, “the Peerless Lady Wing Shot,” the standard cavalcade through the streets, and three magnificent bands of music.

“All kinds, all colours, all tongues, all men fraternally mingling in the picturesque racial camp.”

Like many other youngsters growing up in the 1950s, I came into contact with the Buffalo Bill legend early on in a large picture book packed with Western stories – and also in the pages of a Classics comic book. Through comic books and regular books and movies I became immersed in, and subject to, the myth of the American frontier and supremacy of the white male protagonist (with a few feisty women, such as Annie Oakley and Calamity Jane, thrown in) as much as anyone else coming of age at that time; and I would have a lot of unlearning to do.

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody presented “one of the most popular traveling exhibitions in entertainment history,” says the foreword to Sandra K. Sagala’s book Buffalo Bill on the Silver Screen: The Films of William F. Cody (2013). He was the consummate wild west showman. He apparently had a press agent who provided a personal lustre that gave legitimacy to the spectacular presentations he put on display – with his persona ranging from a supposed buffalo hunter (helping to feed railway workers) to army scout and dramatic actor rolled into one. Along the way he became a national folk hero thanks to the dime-novel accounts of his exploits. To some extent he (and his press agent) fashioned his own legend (including that of riding for the Pony Express), with many if not most of his biographical claims fabricated for the sake of publicity. Loose biographies tended to exaggerate the sensational, if not always true, glimpses of his career, as in this case:

A frame most likely from Life of Buffalo Bill (1912), showing scenes of the older William F. Cody on horseback, and a dream sequence with a younger Buffalo Bill, plus views of the Wild West Show tour. YouTube.

Born near LeClaire in Scott County, Iowa, in 1846, Buffalo Bill Cody was already an Old West legend before mounting his famous Wild West show, which traveled the United States and Europe.

Although some of the biographical claims are suspect, to his credit he was, in his long career, not only something of a champion of women’s rights but also a conservationist who respected indigenous peoples and supported their civil rights. He employed numerous Native Americans in his shows. He once said, “Every Indian outbreak that I have ever known has resulted from broken promises and broken treaties by the government.” (Although the program guide for his show also suggested that Indians were “doomed . . . to extinction like the buffalo they once hunted.”) For one run of the show he hired Chief Sitting Bull, who, he said, had “masterminded Custer’s defeat.” The famous sharpshooter Annie Oakley and Deadwood’s Calamity Jane (Martha Jane Cannary) were part of his crew for years — and, at some point, the “champion lady bucking horse rider of the world” (as demonstrated on film).

Still, although he thought of himself as an educator, his desire to entertain and make money — which, from his point of view, necessitated plenty of “action” — had a lasting impact. Perhaps more than anyone else — always “combining myth with sensational melodrama” — he helped to establish the conventions of the western genre.

The title frame of the film as reconstructed years later by Blackhawk productions — which might not have been the title that the audience at the Crystal saw. YouTube.

Oct. 8, 1910, Moving Picture World, p.389.

Cody, having financial problems by 1907, had merged his wild west show with Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East show in 1908. The title of the motion picture assembled for release in September 1910 (and shown at the Crystal) might have been Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Far East or perhaps Buffalo Bill Bids You Good-Bye, or perhaps even something else. Titles seemed to vary in those days, and exhibitors could be fast and loose with them. In any case, it featured the Wild West show and other scenes of supposed frontier days. Only portions of the complete film have survived, and they were compiled only in 1992 by the Buffalo Bill Historical Center staff in Cody, Wyoming.

At a time when most films screened were short one-reelers, it was one of the early “features” that were coming onto the scene, with three reels and 3,000 feet. Distribution was handled by the Motion Picture Distributing & Sales Co., which sold “exclusive city and states rights” as of Sept. 17. In Ontario (which the film industry considered part of that terrain) the rights went to J.A. Morrison of Meadford, as of Nov. 26, and the picture quickly made its way to Peterborough from there. A lecturer accompanied the film to “describe every scene.” There would have been music, too, supplied by the Crystal’s usual musicians or, at the very least, one pianist.

A frame from the 1910 film. In one of the extant sequences, a “Grand Review” of the wild west show, “Cody rides into the scene and sweeps off his hat.” Segala: Buffalo Bill and the Silver Screen, p.36; YouTube.

Despite the success of that big film — and subsequent participation in and marketing of another film called The Life of Buffalo Bill, by 1913 Cody’s travelling show was near bankruptcy and finished. He complained, as writer Sandra K. Sagala points out, that the movies “had usurped this Wild West Business,” and, ironically, it was his live show that influenced countless portrayals of the U.S. frontier in both cinema and literature. (Short pieces of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show had itself been captured in the first Kinetoscope films made in 1894.) The success of the motion pictures led to the formation in 1913 of the Col. W.F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) Historical Pictures Company to produce, without much success, short films on “the Indian wars.” Buffalo Bill made his final appearance with the Miller Brothers and Arlington 101 Ranch Wild West show in 1916 (with a theme of military preparedness). He died in 1917 at the age of seventy-one.

Moving Picture World, May 4, 1912, p.467.

Examiner, Nov. 1, 1922, p.11. A Buffalo Bill serial at the Royal Theatre. This film, produced 1922–23 by Universal Pictures, is presumed lost.

Examiner, Aug. 30, 1944, p.7. A first run showing of Buffalo Bill — plus Canada Carries On and the Latest Canadian Universal News.

Examiner, Feb. 16, 1946, p.7. Joel McCrea’s Buffalo Bill returns for a second run at the Centre as part of a double feature.

*****

Peterborough had another curious connection with Buffalo Bill that stretched well beyond his celluloid and personal appearances.

Oklahoma Jack, a publicity photo from his show days, sometime before 1911. PMA, Oklahoma Jack fonds.

A fellow named Thomas Harper Aiken came to town in the early 1920s. He took up residence and stayed for the rest of his life. Aitken was born in Lowell, Mass., in November 1884, but spent his early life on a ranch in northwest Texas. There he learned the trade of a cowhand — roping steers, branding calves, driving in stock from the range, and all the rest.

During that time, in his wide-ranging travels for the ranch he met up with a young Mexican woman in the foothills of Oklahoma. He took a shining to her and once in a while he’d disappear from the Texas ranch. “Those that cared,” it was said, “knew he was up visiting his senorita in Oklahoma.”

When he turned eighteen — around 1902–3 — Aitken joined Bill Cody’s wild west show and, in deference to that young lady, he adopted the stage name “Oklahoma Jack.” By that time, he later explained, the “Mexican filly” he was named after was dead. “She caught a stray bullet in a honky-tonk riot in San Antone.”

With the Buffalo Bill show, as later recounted, he joined “a rough and tumble crew, where it was survival of the fittest as in any Old West saloon, and where modesty was unheard of in best show-biz style.”

He would never lose the Southern twang to his accent and a penchant for good story-telling.

When he arrived in Peterborough around 1921, living in a house at 381 Mark St., he identified himself as a traveller for the Colonial Hide Co. (a subsidiary of the Consolidated Rendering Co. of Boston). By 1925 he was working at the Brinton-Peterborough Carpet Company, becoming a weaver and eventually living with his wife, Mary, at 88 St. James Street, which ran west off of Park St. in the south end. In the 1940s he had a stint at the Genelco plant, set up for wartime purposes in the CGE, before getting a job at the De Laval dairy supply plant. In 1945–46 Aitken’s address shifted to 568 King George Street, but it seems he was still living on the same property; St. James Street disappeared, replaced by a continuation of King George. In his spare time Aitken kept a tidy greenhouse out back. In his later years he did some woodworking and operated a gardening centre out of his home – calling it “Okie’s Gardens.”

Thomas Harper Aiken in his backyard in Peterborough, cigar in mouth and in his “Oklahoma Jack” outfit — having pulled his “furry chaps” out of an old trunk. PMA, Roy Studio photo, undated, Oklahoma Jack fonds.

PMA, Oklahoma Jack fonds.

In September 1946 the Examiner’s Ray Timson met up with Oklahoma Jack in his backyard greenhouse, where the ex-cowboy was busy watering some “mums.” Okie had a two-inch, unlighted “seegar” in his mouth, and as he spoke he rolled it from one side of his mouth to the other — he “literally performed a flip — but a quick snap retrieved it.”

After a short while Okie exclaimed, “Cuss yo! I can’t chew the fat hyah — let’s go,” and took the reporter inside.

In his parlor he kept an old black trunk full of mementos of his show business days — “those hectic days” — with a legend printed on the top: “The Buckin’ Sellers, Sharpshooting, Trickriding and Roping.” It was filled with handbills of theatres and acts he had appeared in along with grey, furry chaps, leather bull-whips, neckerchiefs, vests with “Indian braid,” wristcuffs, two six-guns, ammunition belts, holsters, ten-gallon hats, and “a small mountain of telegrams addressed to Oklahoma Jack, and seeking engagement for countless theatres.”

When reporter Ray Timson asked him if he was ever in “any real gun-play,” Okie replied, “Oh, a bit, but I don’t say much about that.” He was quite willing to display his scars: one on the top of his hand and another on the bottom, where a .45 bullet had entered and gone right through. “And I have a couple of more traces here on my backside,” he said. His wife, Mary, added: “And the one on your neck.”

Examiner, Sept. 12, 1946, p.9.

“ ‘That’s a knife-stab,’ he barked, as though insulted.”

Of the present-day movie cowboys he said: “Those fakers? I can’t sit in a show and watch them. Their hoofbeats sound like cocoanuts bouncing on a marble terrace. Why don’t they get that earthen thump into it? And their gun-fights? They all have nine lives.”

Aitken died in September 1959 after being in poor health for a month or so. In addition to his wife he left behind two daughters, Mrs. Joseph Zetter (Martha) of Stockton, Cal., and Mrs. James Hall (Warreen) of Peterborough. He had four brothers still living: Frank of Pennsylvania, William of Camden, N.J., and “another somewhere in the U.S.”

*****

A shorter version of this article (with no Oklahoma Jack) appeared in Peterborough Historical Society Bulletin, Issue 470, November 2020.

Sources

Peterborough newspapers, November—December 1910: Evening Examiner, Daily Review, Morning Times.

Peterborough Museum and Archives (PMA) — Oklahoma Jack fonds.

“Murder, Marriage and the Pony Express: Ten Things You Didn’t Know about Buffalo Bill,” Smithsonian Magazine, January 10, 2017 <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/murder-marriage-and-pony-express-10-things-you-didnt-know-about-buffalo-bill-180961736/>.

“The Shrewd Press Agent Who Transformed William Cody into Larger-Than-Life Buffalo Bill,” Smithsonian Magazine, Oct, 19, 2018 <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/shrewd-press-agent-who-transformed-william-cody-into-larger-than-life-buffalo-bill-180970591/>.

“Buffalo Bill Cody Biography,” Biography Newsletter <https://www.biography.com/performer/buffalo-bill-cody>.

Sandra K. Sagala, Buffalo Bill on the Silver Screen: The Films of William F. Cody (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013).

Buffalo Bill, Wikipedia entry <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buffalo_Bill>.

“Buffalo Bill Cody Biography,” Biography Newsletter <https://www.biography.com/performer/buffalo-bill-cody>.

Moving Picture World, “Buffalo Bill — The Father of the Feature,” July 11, 1914, p.172.

Moving Picture World, Buffalo Bill Rights, May 4, 1912, p.438.

Motion Pictures:

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Far East, 1910 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M9A1-2orzqQ>.

Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. 1898, 1902, 1910 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Bl4_2HhzdI>.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, 1898, 1902, 1910, Blackhawk Films, Oklahoma Historical Society <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Bl4_2HhzdI&t=422s>.

Buffalo Bill (1908) - William F. Cody on Horseback - Wild West Show Tour <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_pZ8k00qyLk>.