“The Nickelodeons are important factors in the entertainment of the masses to-day, and they, springing up everywhere and in every conceivable city, town or hamlet . . . are all getting a good livelihood, and the prospects for the future are bright.”

The Rise and Fall of Wonderland. The city was by no means an easy place to break into. In April 1907 a couple of men came to town from London, Ontario, looking for a downtown spot to place a “vaudeville show.” But, a report said, it was “almost impossible to secure a store in the business section” given the “great demand for business places.” Soon enough, though, crowds of people no longer had to go to the outdoors of Jackson Park or other occasional indoor spaces to see the motion picture novelties.

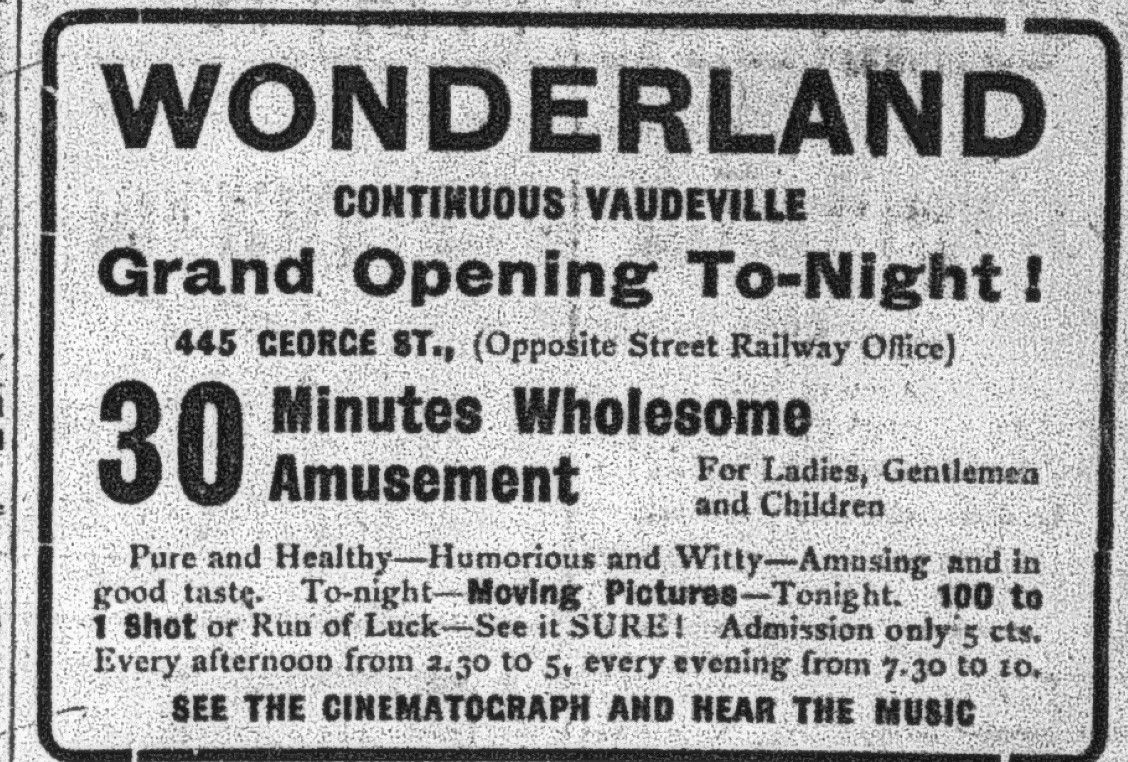

Examiner, July 30, 1907.

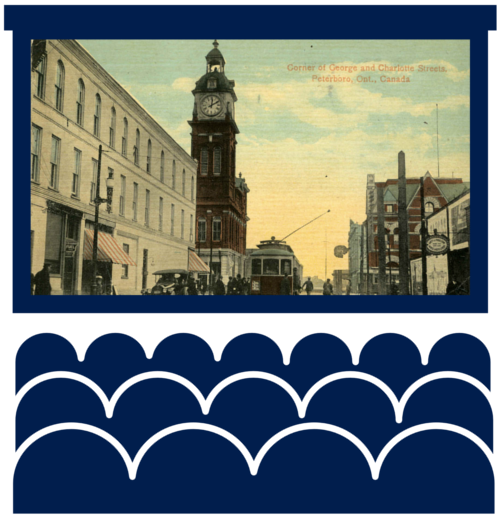

Peterborough’s Wonderland opened on Thursday, July 25, 1907, just north of Brock Street. A year before that the space at 445 George had been occupied by a tailor, V. Reynolds (and the year before that, H. Engel, “dry goods, etc.”). If you had walked a few steps north along George that day, past Wonderland – on a sidewalk bordering an unpaved main street – you would have seen a vacant lot with some billboards and, beyond that, at no. 459, the Bethany Tabernacle (which later became the Church of the Open Bible). Just above that was the relatively new and splendid Romanesque Revival YMCA building (constructed in 1886–87) on the corner of George and Murray. South of Wonderland, at no. 443, was T.A. Redner, a locksmith (who also made and repaired umbrellas). To make sure that newspaper readers could find the theatre, a newspaper ad pointed out that it was “OPPOSITE Street Railway Office.” That same year Rev. Edwin Pearson became minister of George Street Methodist Church just two blocks north – that fall his son, future prime minister Lester B. Pearson, would be attending Central Public School a couple of blocks east of the cinema.

A brief news item on the theatre’s opening day noted:

Messrs. Lamb and Stutt, proprietors of the new “Wonderland” and Continuous Vaudeville, 445 George street, will give their opening attraction to-night, commencing at 7.30. The startling moving picture views, depicting Old Homestead Life, in the “100 to 1 Shot,” or Run of Luck, the Cinematograph and music, fill in a varied and interesting programme. The admission is only 5 cents for a continuous 30-minute show.

J.W. Lamb and F.A. Stutt, both “late of Toronto,” shouted out to potential patrons: “Step in and see the cinematographe and hear the music.”

We have no way of telling how many people turned out on what was a fine summer evening to see a motion picture in one of the city’s first standalone theatres, or in the following days – like most storefront nickelodeons the theatre had room only for a couple of hundred people – but thanks to that short notice we know what they saw. The 100 to 1 Shot; or, A Run of Luck had been released a year earlier by the Vitagraph Co. of America and, at 640 feet, was about 11 minutes long. But within that short time it presented a breathtaking story that may well have had the audience members on the edges of their uncomfortable seats and perhaps even shedding a tear or two. As the story goes, when a farm is threatened with the foreclosure of its mortgage the farmer’s daughter appeals to her “sweetheart” for help. He has precious little money himself, but decides to go to New York (the city of riches, presumably) by train to see if he can come up with some quick cash. After arriving at Grand Central Station he finds out about a horse race taking place that very day. He accidentally gets a tip on a long-shot horse named “Tommy Foster,” bets “his all,” and – of course – wins. Hiring a fast automobile, he gets back to the farm just in the nick of time. An ad for the picture pulled no punches: “A Great Film – A Sensational Film – Thrilling with absorbing, pulsating interest from start to close.”

Evening Examiner, July 25, 1907, p.8.

The 100 to 1 Shot was an extraordinary little film for people who may well have been going to a motion picture theatre for the first time. They may have seen the funeral of Queen Victoria or watched Queen Alexandra reviewing the colonial troops, and they may have seen a film or two at Jackson Park over the past three summers; but they had probably never seen anything quite like this before – and, after all, that is one of the reasons we go to moving pictures: to see something we’ve never seen before, and participate in this experience with the others around us. With its social theme (eviction) and the ultimate triumph of its characters against all odds – in essence, taking up the well-established Horatio Alger myth – the film was among the first in a long line that formed the “classical Hollywood narrative form” – which continues, as one critic points out, to the blockbusters of the present day. But the film was also the very latest when it came to technique. It was among the very first to use cross-cutting, showing events happening in two different places and jumping back and forth between them.

A much later account, written in 1939, recalled an early comedy shown at the Wonderland, which, the article said, “old patrons of the silver screen” would remember:

It dealt with the experience of a comedian who found himself in the path of a street roller which knocked him down, rolled him as flat as a circus poster and then he was picked up and hammered back into shape again. The picture was considered a wow in those days.

In the article encouraging readers to come out for this entertainment, the Examiner writer added quite directly, “Don’t be afraid to bring your ladies and families” – clearly assuming, perhaps wrongly, that the paper’s male readers were fully in charge of such events and revealing more than a little concern over the cheap theatre’s low price and somewhat tawdry appearance – and, even worse, the sordid reputation that was quickly growing up around these new “electric theatres” (as they were called in 1907, and for some time after). To many people (and critics) the motion picture had “low-class associations.” They were a cut below the opera houses. For a time the pictures were referred to as “the poor man’s amusement” (although records reveal that they were frequented to a considerable degree by women and children). They could be noisy, unruly places, not quite suitable for the supposedly refined. At times the fare offered up on the screens was “naughty,” or trashy. A large number of the pictures shown, some said, were “unwholesome,” and, even worse, sometimes “largely suggestive of evil” – “schools for robbery to morbid and degenerate youth.” People worried, not for the last time, about just what was going on in the darkness or even “semi-darkness” of the theatres.