“The attempts to depict the attitudes of animals in motion probably began with art itself, if indeed, it was not the origins of art itself; and upon the walls of the ancient temples of Egypt, we still find pictures of, perhaps, the very earliest attempts to illustrate animals in motion.”

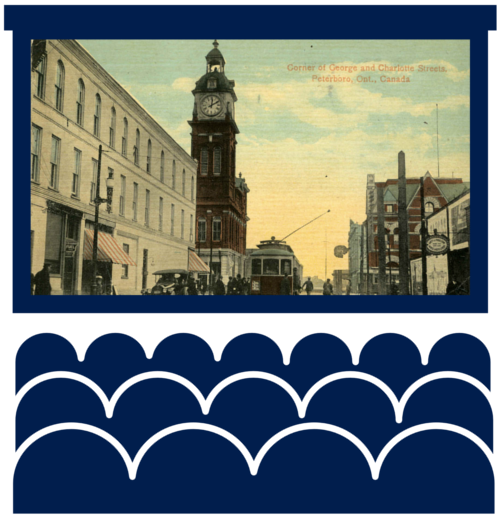

Thursday evening, January 21, 1897, downtown Peterborough: Bradburn’s Opera House, with its seats and upper boxes for 1,000 people, was the place to be.

Most if not all of the people who came out to the opera house on George Street on a clear but cold mid-winter evening would not have known quite what to expect.

According to reports, “a good audience” turned out, which indicates that the Bradburn was not quite “packed to the doors” (a common epithet of the times). The attendees had perhaps seen the newspaper advertisement, “Realistic motion pictures . . . Six Days Only.” They had paid their twenty-five cents and settled into their seats with considerable curiosity. They were there to witness with their own eyes something that had never before been seen in town.

As they came into the opera house auditorium, the people that evening could see a large canvas, about ten feet square, hanging down across the front of the stage. Hidden “away in the rear of the hall,” as one audience member noted, was “an enclosed square, from which light protrudes.” The first impression of one witness on entering the opera hall was that “a magic lantern exhibition” was to take place — referring to a common amusement activity of the time, presumably making it a somewhat familiar affair.

At 7:30 p.m. the theatre lamps were turned down. A rhythmic and somehow reassuring clatter came from somewhere at the back of the room. (Perhaps the Bradburn’s orchestra began to play to drown out the noise and draw attention forward.) Someone was beginning to hand-crank the machine at the back – the Cinématographe projector – at a rate of two revolutions per second, carefully feeding the film past the projection lens. An Examiner report took pains to explain the procedure:

The pictures, about the size of a postage stamp, are on a long, narrow continuous film, nearly a hundred feet in length, and an inch in width, and reproduced by being passed very rapidly before a powerful electric lamp, and magnified to life size.

When an “unusually bright” stream of light came beaming out across the length of the large auditorium, on the stage in front of them the spectators saw photographic pictures “flashing” and jumping – “thrown,” as it was usually said in those days – upon the canvas screen. According to reports, audience members were surprised to see “figures of life size and actually moving and acting as though the original view were before the spectator’s eye.”

At one point the viewers saw on the screen a cloud of dust in the distance, and then slowly “a squadron of French cuirassiers” came into view. The horseback riders grew more distinct as a few short seconds passed. The riders came closer, “charging furiously, the dust rolling from the horses’ feet.” At least one spectator believed the scene was “as near life as stirring reality.” The horses came “so near that they appear about to rush upon the spectators.”

What those spectators saw: the “Cuirassiers à cheval,” from the Lumière brothers’ Cinématographe films, from Lyon, France, 1896.

Those first motion-picture spectators in the Bradburn that evening watched scene after scene – some thirty-two “scenes” in all – through an hour-long program. English immigrants who had arrived in Canada not long before might even have noticed sights and places they recognized. The films, said one writer who was there, showed people coming off a Thames steamer, “motley” people on Regent street, “Rotten Row, with its gay life,” and “sea scenes, with the rollers breaking into spray upon the rocks.” According to another scribe, the audience also saw scenes of a “beach on the sea shore”:

The waves are rolling and splashing upon the banks as realistic as though one were standing upon the rocky shores of Stony Lake. Soon a mother and her family run down upon the wharf and in turn they jump into the lake, and the audience watched with wonderment the persons swimming, running upon the beach and then diving into the water again. Scenes such as these were continually before the audience and that the movements of people, card playing, working in the fields, departing in trains, etc., could be so vividly portrayed was indeed a marvel.

The newspaper report does not mention what, if any, sounds or music were heard by that audience that evening. (In July 1896 a New York Cinématographe screening included “the flash of sabers, noise of guns, and all the other realistic theatrical effects.”) Nevertheless, those scenes and “life-like movements,” and that evening, marked the beginning of the motion-picture-going experience in Peterborough.