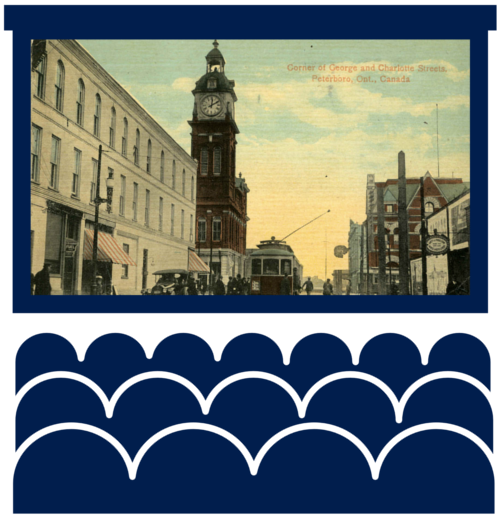

Peterborough Examiner, June 16, 1909, p.7. At this time, with motion pictures in their infancy, Peterborough had two dedicated theatres, the Crystal and the Royal (plus the Grand Opera House), with more to come.

Cinema history is local history.

– Jeffrey Klenotic, “A Theatre Near You,” Mapping Movies, 2016

In the beginning was created the heavens and the earth and the moving picture.

– William H. Kitchell, “The Importance of Good ‘Business,’” Moving Picture World, 1912

What do you think is the purpose of life – to go to the movies and dally with every girl that comes along?”

– Walker Percy, The Moviegoer, 1961

It is good entertainment. You will like the story and the actors and the tempo and the ending. It is real life – the most satisfactory material for stories or theatrical efforts.

– Jeanette (Cathleen McCarthy), movie review, Peterborough Examiner, 1931

My friend and I have a rule when we go to plays and movies: neither of us is allowed to talk when the play or the movie is over if we perceive the other has been upset or moved by what we’ve just seen. Surely there’s nothing worse than somebody breaking in on your own reflections with: “Wow! What a piece of garbage!” Or even with: “Wasn’t that terrific!” It doesn’t really matter whether the voice breaking agrees with you or disagrees. The point is, the only voice that matters when an experience is over is the voice of the experience itself.

– Margaret Laurence, The Diviners, 1974

“Going to the show?” My memories of growing up in Peterborough – I have to say it was a while back, from the late 1940s into the early 1960s – are flooded with a steady and I hope not too damaging rush of movie-going experience.

When I was quite young and before we had TV, my family regularly went out together to catch a movie. We were a working-class family – in the late 1940s and early 1950s my father was a “lab assistant” at the city’s then-biggest employer, Canadian General Electric – and “going out” to movies as a family, I later found, had from the start been a working-class form of amusement. When I was a bit older, even after television came along I kept going to the movies, usually with friends, later with partners and children and others, and I’ve never stopped going.

Movies in the late 1940s and early 1950s were a form of cheap family entertainment – adult tickets sold for maybe fifty cents a person, depending on the movie, and children’s tickets for much less. In the 1950s my parents would send me off to Saturday-afternoon movies with a quarter – fifteen cents to get in, and a dime for a small box of popcorn. In the late forties and early fifties the movie theatres ordinarily changed their movies twice a week, so there was always something new to see. Sometimes, so I’ve been told, families went to movies not just once but twice a week, or more.

From around the time I started going to movies: the Examiner editor (1942—63), playwright and novelist Robertson Davies, liked going too; and he had a good sense of the clichéd niceties of plot. “The Marchbanks Correspondence,” Peterborough Examiner, Feb. 11, 1950, p.4.

The postwar movies I grew up with tended to follow a standard plot – with good versus evil constantly personified: good guys, bad guys, good girls, bad girls – and time after time I saw (thanks especially to a production code) the good winning out, all very reassuringly, though it is not particularly true to life. Happy endings were the norm, and, I might ask, what exactly did this mean for an impressionable and uncritical boy like myself in that period? Peter Biskind touches on this point in his book Seeing Is Believing, on what we may or may not have learned from watching movies in the 1950s: “To understand the ideology of films, it is essential to ask who lives happily ever after and who dies, who falls ill and who recovers, who strikes it rich and who loses everything, who benefits and who pays – and why.” I was there, soaking it all in, responding as well as enjoying, and, I suppose, learning.

The heroes and heroines fell in love at the drop of a dime (or the fifteen cents that a youngster had to pay to get into the movie on a Saturday afternoon). There were usually certain obstacles, but they were quickly overcome. The movie-going of the time offered a variety of goods: the “shows” might include a double feature (one of them possibly a B movie, quite often a Western), a newsreel, a live-action comedy short, a documentary short (a “travelogue,” perhaps), musical short films, and/or cartoon shorts, all for the relatively cheap price. The price could vary sometimes depending on the quality of the film and theatre. An extravaganza like The Greatest Show on Earth (1952, with Charlton Heston, Betty Hutton, and James Stewart, among a long list of other stars) might cost more than a routine actioner like Thunder in the East (1953, with Alan Ladd and Deborah Kerr). I recall going to both of those shows with my parents – and both of them had certain scenes that bowled me over.

People in those days drifted in and out of the theatre at any old time, often with no mind as to when a particular film was starting. It was the period of “continuous admissions” or “continuous performances,” with brief intermissions. The programs, with all their various bits and pieces, had one film following another through the whole day, or at least from early afternoon (even on weekdays) to late evening. After grabbing some popcorn from the concession booth, you would go in while the movie was in progress. The theatre was dark except for the picture on the screen, but uniformed ushers with flashlights would show you to a seat. You would normally stay through the whole cycle and leave, even if it was in the middle of a feature, when you recognized a scene from the beginning of your visit. That accounts for the phrase “This is where we came in . . .” In some cases, you’d know the ending before you saw the beginning – but you could still enjoy the film. As time went by, like other people I began to find this a less than satisfactory way of seeing motion pictures. In any case, nowadays it is no longer an option – theatres are “cleared” after every performance.

And, indeed, now, in the twenty-first century, much has changed. But, to my considerable surprise, much has also remained more or less the same . . .

****

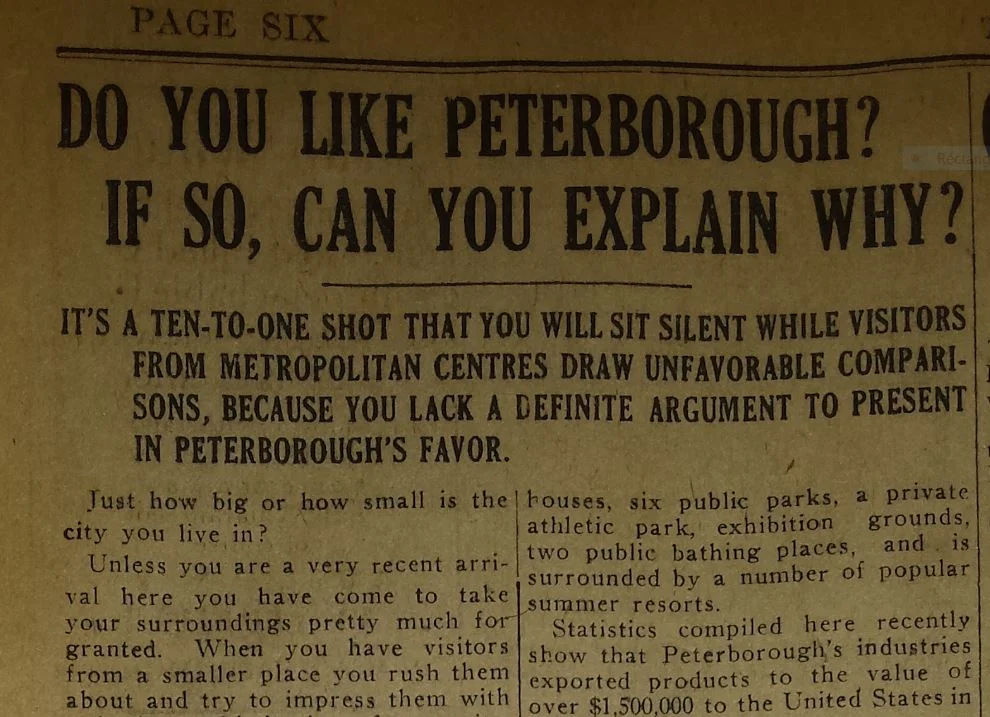

This book is inspired, then, by a lasting love of movies and movie-going and especially by a fascination with where and how we’ve seen movies over the years – and with what we were seeing – and, often not seeing. But it is also about that particular experience as shaped in the middle-sized city of Peterborough, historically a smallish industrialized city (now post-industrial) that, as the evidence shows, not only appeared jealous of the urban attractions of the large city (Toronto) but also, over the decades, retained a rural focus too, as the centrepiece of both a large surrounding agricultural area and, primarily to the north, a more natural environment of forests, lakes, and rivers – an environment that shifted from massive early lumbering practices to recreation and leisure. Peterborough has in essence been a hinterland area that, like other such areas – but with some differences – became infused with, or found its own particular place in, the metropolitan “modernity of modern cinema,” and shared in the creation, over time, of a mass market.

Peterborough Examiner, Jan. 3, 1940, p.11. What’s on at the movies? Even Dagwood wants to know. . .

Photoplay, February 1953, p.12. My movie-going experience began in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when it seemed that “going to the movies” was simply the best thing to do.

For well over a century motion pictures have been a means through which many of us can escape, for at least an hour or two, the world at hand. As early as 1907 a Peterborough theatre’s ad told people in town to get rid of “all worry and trouble” by coming to see the pictures. The movie theatre could also, perhaps more rarely, be a dangerous and subversive place, at least in some people’s eyes. It could be a refuge and – particularly for teenagers – a dark room for groping or necking or, at the very least, for holding hands in relative private (“holding hands in the picture show, when all the lights are low,” says the song). Gerry Armstrong of Peterborough was once an usher at the Capitol Theatre and tells me that he particularly liked when he was assigned to the balcony “because all the lovers liked to go up there.”

Examiner, Feb. 10, 1948, p.9. This fascinating little article offers a glimpse of people who either could not afford to go to the show, or were not physically able to do so. Sometimes people needed help getting there. It’s hard to believe, given the increase in attendance in the 1940s, that someone had never even been to the pictures before. Anson House was a Protestant “old folks home.” The House of Refuge (a provincially mandated county-built and operated long-term care facility), in Lakefield, and Providence House, 364 Rogers (Roman Catholic) were institutions for the needy and aged. The movie they got to see that afternoon? Welcome Stranger (1947) with Bing Crosby, Joan Caulfield, and Barry Fitzgerald, along with a couple of short subjects: George Pal Puppetoons and Sponge Divers, with the Latest Canadian Metro News.

Theatres can be a location for connecting in more ways than one. A legendary Toronto Maple Leafs hockey player and Hall of Famer – Irvine “Ace” Bailey – played with the Peterborough Petes as a young man, from 1924 to 1926. When he went with a friend to a Peterborough “picture house” one day in November 1926, the house manager came and tapped him on the shoulder. He was led into the office for a phone call with the owner of the Toronto St. Pats, soon to be renamed the Maple Leafs. By the end of the talk he’d been offered a large contract to begin his professional career.

George Street, looking north from Charlotte Street, mid-August 1954, around the time I was going to movies as a youngster. If you look closely you can see the Centre Theatre up the street on the right, with a marquee advertising Crossed Swords, with Errol Flynn and Gina Lollobrigida. Peterborough Museum and Archives, P-14-010-1.

The movies have for most of us brought the outside world into our lives; they have told us something about ourselves, whether we wanted to find it out or not; they have opened the door to what is, or was, going on in other people’s lives. They have told stories that otherwise would not have been told. On many occasions, too, as writer Steven J. Ross argues, “Going to the movies was more than just an evening’s entertainment. It was an experience that could transform lives.” In his book Screening Out the Past, Lary May describes the great cinema effect – how audiences at motion pictures historically found themselves able to “relax much of their active rational minds, and let the images penetrate deep into their subconscious. Mesmerized in the darkness and absorbed into the crowd, viewers shed the concerns of social life, and even relinquished their individuality, giving themselves up to the magnified, larger-than-life images that raced across the screen.”

The book is also at least partly about the evolution of the Peterborough downtown, and where people living in the city could go to see moving pictures as well as what they could see; and how the various venues were transformed over time. Indeed, one of Peterborough’s earlier movie-theatre spaces actually became “The Venue.” At first movies in Peterborough were screened in opera houses. They were shown outdoors in parks and also in churches, then in makeshift storefront spaces — “nickelodeons” — and after that in standalone movie houses, sometimes called “palaces,” built for the purpose. Later on motion pictures drew people out to drive-ins and most recently to huge, impersonal multiplex corporate popcorn-and-taco-selling beehives.

Downtown cigar merchant Mehail Pappakeriazes — known around town as Mike Pappas — established one of the first standalone motion picture theatres in Peterborough: The Royal (1908—25). This ad was in the Examiner, July 1908, p.1, not long before the theatre opened.

Most significantly, perhaps, the ownership or control of motion picture exhibition in Peterborough went through a dramatic, and relatively quick, transformation. Early exhibitors or proprietors included not just a couple of prominent business families (the Bradburns, who had a hand in both of the early “opera houses”) and Turners (manufacturers of awnings and sails and other goods), but also a blacksmith, a Greek cigar-store owner, a veterinarian (and livery business owner), and jewellers. Other people drifted in and out of town to take part in the business. The result was, in the words of Charles Tepperman (speaking of the arrival of cinema in Ottawa), a “conflation of science, amusement and local enterprise.” But by the 1920s large corporations had moved in to take control of film exhibition; a few local “independents” remained for a couple of decades, but they had a hard go of it with the Hollywood “production-distribution oligopoly” dictating terms and delivering product. By 1956 the last of the independent theatres, the Centre, was gone. Lary May asserts the importance of this shift by suggesting how the Hollywood factory system, with its strict self-regulation amounting to censorship, was a means “of transferring the old moral guardianship of the small city and town to the movie corporations.”

All of this activity had an immensely important effect on the cultural makeup of urban areas, as cinema historian Paul S. Moore nicely articulates:

“As builders of real estate in the downtowns and neighbourhoods of almost every Canadian city, and, later, key tenants in suburban malls and big-box developments, Odeon, Famous Players, and hundreds of smaller independent entrepreneurs helped to shape the modern culture of Canadian cities and the viewing practices of Canadian audiences.”

The dazzling displays of those businesses enterprises are apparent in the many photographs of Peterborough’s one-time (but now long-lost) “Entertainment District” (which you can see on the top of the home page and other pages of this website). But even after the corporations moved in, for decades local businesspeople made at least four attempts to establish independent repertory theatres. While those efforts failed to meet with lasting success, they and many other possibilities that offered alternative ways of seeing movies – festivals and film series and Peterborough Museum (Muse) screenings – have continued to thrive. Hollywood has never been enough.

*****

Evening Examiner, Jan. 22,1897. The motion pictures arrive at Peterborough’s Bradburn’s Opera House.

From the very beginning – the screening of the Cinématographe in January 1897 – the local press covered the attractions, but quite spottily, and mainly as a new technological marvel. From 1907, as theatres began to be established, the daily newspapers (for a while there were three of them) carried advertisements and notices paid for and placed by the exhibitors, thus helping to encourage and shape readers’ responses. “The movies were news before they were art,” writes cinema historian Richard Koszarski, and for the first decade or two any reviews that appeared in the press “were straightforward accounts of news events.” At first, people didn’t know quite what to call the new phenomenon. A house that showed motion pictures was said to be “an amusement place.” Or a nickelodeon, because many of the houses that sprang up overnight in vacant storefronts charged only a nickel for the cheap entertainment. Sometimes they were simply called “five cent shows.” Another variation was “nickelette.” Early on they were called photoplay or photo-drama houses, theatoriums, electric theatres, picture theatres, and moving (or motion) picture houses. (Boston had an “amusement palace” open in April 1907.)

What exactly was it that was being “thrown” on the screens in these places? For a while, “animated photographs” or “living pictures” were among the terms used, but these names were soon overtaken (understandably) by “photoplays” or “moving pictures” or “picture shows.” By 1912 a columnist in the industry journal Motion Picture World was strongly objecting to employment of the newly coined word “movie,” which had started appearing as a short form in newspaper comic strips a few years earlier. The writer argued that the term was a kind of “street slang” that children had been using for the past couple of years, but which he considered “cheap, inelegant and not in any way suggestive of the entertainment it is supposed to represent.”

Evening Review, Jan. 15, 1913, p.2.

A couple of decades into the twentieth century that cheap word “movie” had firmly taken hold, and the motion pictures shown in cities like Peterborough – films that had at first come from England, France, Italy, Denmark, and other countries as well as scattered locations in the Eastern United States – now came almost entirely from Hollywood, California. Only a tiny minority of films originated in Canada itself. Local audiences started by viewing short silent films offering up thin slices of documentary or fantasy life. The films, though, were usually not “silent” – the theatres necessarily had phonograph machines, pianos and piano players, perhaps a trap drummer, or small orchestras playing music – sometimes they even had someone behind or near the screen producing sound effects – and for a while the film showings included lecturers who explained what was going on. At first film screenings were regularly accompanied by popular “illustrated songs” and/or vaudeville acts. The motion picture experience went from there to longer, more sophisticated, and sometimes spectacular narratives or “features.” It went from silent to “talkies,” from piano and orchestra accompaniment to Dolby Sound; from mainly black and white to Technicolor and 3-D; from standard 35 mm projection to widescreen Cinemascope and VistaVision and today’s digital projection.

“Please, Mister, Take Us In?” The motion picture habit develops early. Motion Picture Magazine, December 1913, p.90.

All of these moving pictures take us places – but where? That depends on what you see. When you see primarily Hollywood movies for a couple of decades, you are going primarily to the same select places time after time, though with a reasonable amount of variation and suspense. It seldom becomes boring – lots of them are exciting and fascinating journeys involving people you can closely identify with. But then, if you happen to see different kinds of films, you also might just find that other less well known, or perhaps completely unknown, places creep into your itinerary.

There is much in this history of going to moving picture shows from roughly the beginning of the twentieth century to the present that represents joy, pleasure, pure amusement, and even education. But there is also much that represents a less pleasant world – of narrow-mindedness, of binding issues of class, of racism and sexism, of miseducation. Of learning things the wrong way and then having to unlearn them. The century and more in which one generation after another has been going to motion pictures is, after all, the historian Eric Hobsbawm’s “Age of Extremes.” Likewise the story of pictures that move across the decade is not always a pretty one. The history of going to motion pictures over the decades is not a history of seeing a particular, even great, movie now and then, but a history of seeing countless movies over long years – a story of a practice that leads to a larger, complex narrative that is still unfolding and just might lead to better things. For in considering this practice, as Charles Musser argues, “We may even gain a greater freedom to imagine how we as filmmakers, exhibitors, teachers, students, archivists, producers, and spectators might make our cinema, our culture, and our society more open, and more constructive as we live our lives.”

In a certain sense, I am aware that my fascinations with motion pictures and the culture I grew up with in Peterborough have their “paradoxical bases,” to borrow a thought from the reflections of film writer Richard Abel in explaining his own mixed-up, complex personal approach to the subject-matter in one of his books. Part of this is a matter of growing up (and getting older, too) with an overwhelming abundance of Hollywood movies. In his book about the Hollywood blacklist generation, Victor S. Navasky, the long-time editor of The Nation, puts this succinctly in defining Hollywood as a “company town” (and “a fragile one”) that “earned its coherence by holding violently contradictory tendencies in balance: culture vs. commerce, message vs. entertainment, formula vs. originality.” Those contradictions played out on screens everywhere for decades, influencing countless minds, including my own.

Peterborough Weekly Review, July 28, 1921, p.6.

A remarkable trend with the downturn in movie attendance in the 1950s was the continual tie-in of the movie theatres with local merchants. This image represents ony a half-page of the offerings on this occasion. Examiner, Oct. 8, 1954, p.8.

For me a paradox also rests in the contradictions not just of motion pictures but also of the cultural space of the city itself – contradictions that serve at the very least to nurture an irresistible love-hate relationship. Peterborough is the “land of shining waters,” a wonderful place in which to roam. I revel in riding my bike along its paths. The city has its pop-up drumlins and (according to my high-school Latin teacher) its supposed seven hills like Rome, and its river and creeks and grand canal; it has its old rowhouses fashioned for workers, its network of fascinating old tree-lined streets, and its rich combination of industrial and business and cultural life. It has also turned one abandoned railway line after another into fine biking and walking trails. It is a place that has let wartime houses survive in a few scattered pockets but has demolished one grand building after another in the central area, destroying an essential inheritance – buildings, that if left standing, would have enriched the city’s economy and culture beyond measure.

The city’s “demographic averageness” has made it a bellwether riding in political elections and a prime site for market product tests. Its vibrant, busy downtown, so cool – when “cool” is a form of opposition to suburban life – its independent bars and restaurants, its unwavering political activism, its sports, its music, dance, theatre, and visual artists, its writers and educators and the friendliest of tradespeople and retail personnel – its people at large – make it anything but an ordinary place. It is a place where young people come to study at Trent University and end up staying for life. It has edgy little hard-to-find theatres and art galleries. It destroyed two grand opera houses, but then wiser heads prevailed to allow for the survival of a splendid Market Hall performing space.

Examiner, Dec. 3, 1949, p.15. Above, a detail from the map as a whole (left). An interesting mapping of the city’s history — “A Century of Progress” — from 1850 to 1950. The detail above features some of the historic marks of the “amusements.”

George Street, Peterborough, 1984. Examiner photos, F340, Trent Valley Archives. Thanks to John Wadland.

The city has always been a predominantly white space, which has its drawbacks and its restrictions, but it is no longer quite the place that one-time Examiner editor (and eminent novelist) Robertson Davies experienced (after arriving in 1942) as a “stifling” small town lacking “a well-developed inner life.” Worse, Davies found, there was hardly anyone to go out to dinner with. But its conservative edge makes it something of the same place that mystified an entrepreneurial travelling “ice-cream-cone man” who came to town one day in June 1908 trying to sell his strange new confection, only to discover that he couldn’t afford the licence fee that the city fathers were demanding. That man was compelled to sell his cones on the edge of town.

Still, when it comes to motion pictures, in film societies, repertory cinemas, and special annual film festivals Peterboronians have had a chance to see more unusual fare over the years, the kind of stuff you don’t get in the commercial theatres. Indeed, the city was home to one of the most important film festivals in the country: Canadian Images, “Canada’s National Film Festival,” which ran from 1978 to 1984 and was a huge influence not just on its audiences but on what would become the Toronto International Film Festival. Canadian Images was local, and ground-breaking. It was followed by other local festivals, the most recent of which (and now the most long-lasting of all) is ReFrame: Peterborough International Film Festival.

From theatres to school auditoriums and church halls to today’s home entertainment centres and laptop computers: the motion pictures, taking us places we’ve never been, taking us back to places we love, have been around for well over a hundred years. Moving pictures, the record shows, found a ready audience in Peterborough from the beginning, though they were not without their controversies. They represent a community’s cultural and social experience, a way of coming together; they have a history worth celebrating, worth remembering. Going to the movies: from the Colloseum to the Galaxy, it’s a lasting journey, a continuing conversation, a way of life.